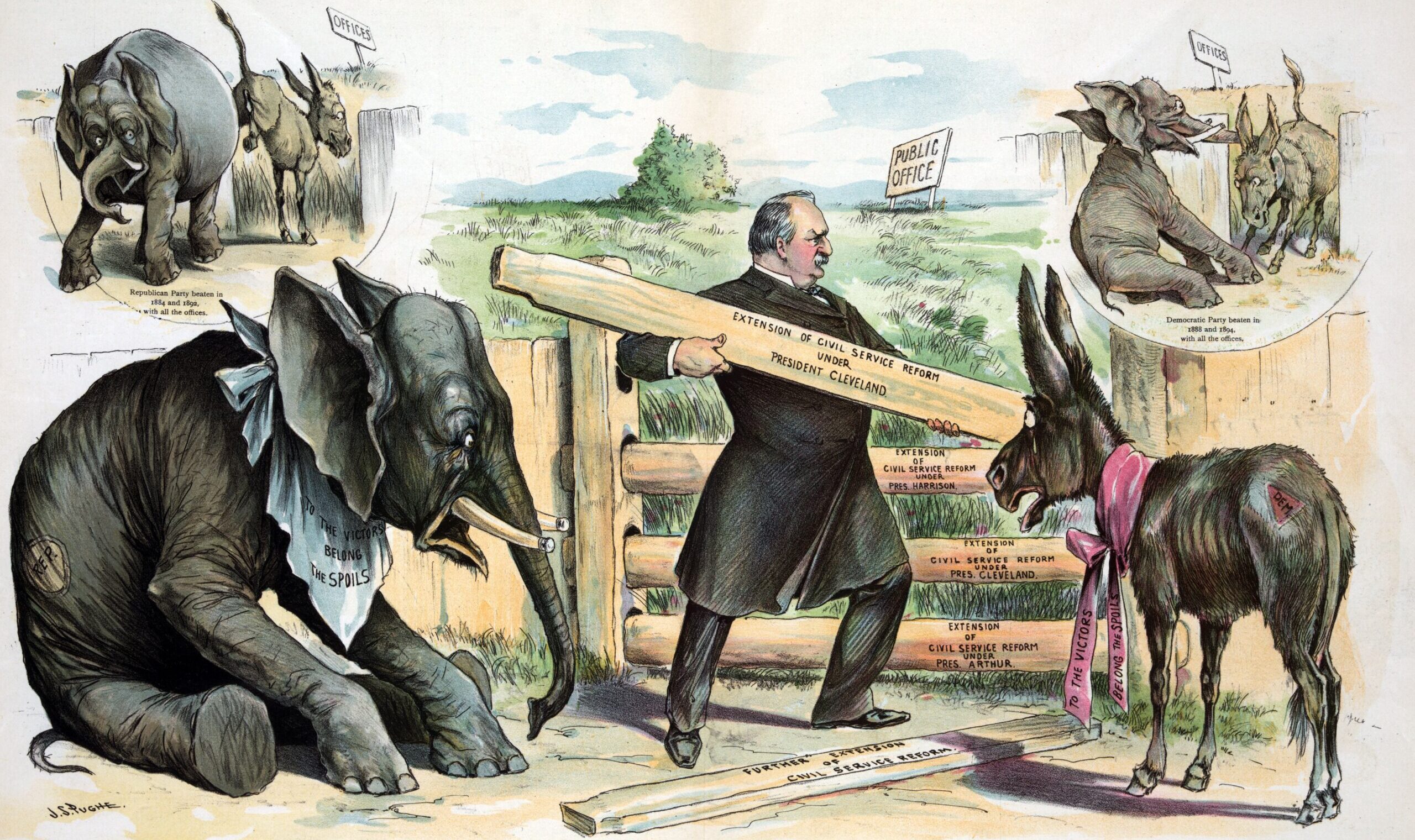

The DOGE of the 1880s

Congress can boost Elon Musk’s government-efficiency efforts.

After years of government failures, an angry Congress confronted the federal bureaucracy. The much-criticized bureaucracy used archaic technology and was badly behind on its business. Many employees didn’t even bother to show up to work in person. Congress and the nation were ready for a thorough overhaul of the executive branch. The year was 1887.

Just as the late Gilded Age bureaucracy was failing to adapt to the industrial age, today’s bureaucracy is proving itself inadequate for the digital age. There is once again a push for fundamental reform, embodied today in Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Lawmakers who support DOGE should draw lessons from the 1880s, when congressional investigations helped drive reform by uncovering bureaucratic failure.

In the 1800s, accusations of government inefficiency and corruption were as common as today. So were congressional investigations of these allegations. Congress, in addition to routine oversight, had conducted at least 63 one-off investigations of particular issues. But all of these investigations relied upon information that bureaucrats voluntarily submitted, so nobody knew what the bureaucracy was hiding.

Although complaints from constituents indicated that delays and mistakes were more serious than agencies admitted, nobody knew the depth or causes of the bureaucracy’s problems. Businessmen felt that agencies were hidebound and that civil servants were lazy, whereas officials felt that the government was inadequately staffed. In 1887, Senator Francis Cockrell hit upon a novel solution: He formed what came to be called the “Cockrell Committee,” whose members set out to see the bureaucracy’s problems with their own eyes.

To acquaint itself with actual government procedure, the committee chose eight representative government tasks, such as purchasing stationary for the Treasury Department and paying the salary of a consul abroad—not the kind of practices that Congress, or anybody really, had taken much interest in before. Members went into the government’s office buildings and observed, from beginning to end, administrative processes. They recorded how forms were passed from department to department and observed the technology that clerks used for their work. They even witnessed the final settlement of a piece of business by Treasury Department accountants. At every point, they interviewed low-level civil servants and invited interested parties to comment.

The Cockrell saga reveals three ways that congressional investigations could boost DOGE’s efforts to improve government efficiency.

First, investigations can uncover and rectify dysfunctional government procedures. In the 1880s, even pro-government senators were shocked at what Cockrell’s committee had discovered. A simple request by the Army to employ two riverboat pilots was handled 76 times by clerks and delivered 94 times by messenger. To pay an office of fewer than 500 people, the Army needed roughly 22,000 documents. Government workers, rather than using typewriters—at the time, a hot new technology—still copied records by hand into logbooks.

Irritated committee members demanded the adoption of implements such as typewriters and cabinets, leading to government modernization. The Pension Office, for instance, responded by becoming the first government agency to introduce duplicating services, the precursors to photocopiers. Reformers today similarly criticize the government’s cumbersome procedures, which rely on hopelessly outdated technology. The Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) tax software, for example, runs on hardware and programming languages from the 1960s.

Musk is making information technology modernization a priority, but the small and nimble DOGE team won’t be able to conduct lengthy and detailed investigations. This is where Congress can offer a helping hand. Congressional investigators should go observe the bureaucracy at work and trace government procedures from beginning to end. Concrete details about, for example, the archaic software that IRS workers use might even capture the public’s imagination. In the 1880s, the Cockrell Committee’s findings generated publicity that bolstered the case for reform and gave energy to modernization. The same could happen today.

Second, investigations can uncover government practices that are not merely dysfunctional, but dishonest. The Cockrell Committee discovered serious problems that agencies had willfully declined to disclose to Congress. Agencies were behind on mandated payments, and in many cases government workers had refused to keep legally required records. For example, at the General Land Office, the most basic legal document—the land tract books—had not been recorded in any way since 1832. Until the Cockrell Committee’s investigation, Congress had never heard of such problems, which arose not only from poor management but contempt for laws.

The Committee was not impressed with what it discovered about the civil service, either. Government employees worked light hours, typically only six and a half to seven hours a day. Further, much of the workforce simply didn’t show up; they paid others to do their work in their place as “substitutes” or “proxies.” This practice was, at best, questionably legal. The committee took a hard line against it, prompting cabinet secretaries to lengthen the federal workday and issue the Victorian equivalent of a return-to-office mandate.

Today, DOGE is working hard to expose questionable government priorities and potential fraud at agencies like USAID and in the civil service broadly. Here too, Congress can investigate the bureaucracy more thoroughly than a small team could. As in the 1880s, agencies are unlikely to admit problems unless they are convinced that the problems will be uncovered one way or another. Once issues are identified, DOGE could home in on the worst excesses—wasteful spending at USAID may be only the tip of the iceberg.

Finally, investigation can help Congress understand the problems that its own laws create. The Cockrell Committee discovered that Congress itself was partially to blame for government dysfunction. Agencies had often complained about nonsensical legal requirements, but Congress had never believed the agencies until the committee saw the problems firsthand.

For instance, Congress had never granted the authority for agencies to get rid of old or needless records. Although agencies had complained, Congress had never acted. But when senators saw the issue in person, their view changed entirely. Cockrell himself noted that useless records took up so much space that “desks were almost on top of one another, while there was hardly elbow room for the clerks.” Congress soon passed the Useless Papers Act, which granted authority to dispose of needless records, solving a problem that had been previously entirely neglected.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Today, government agencies continue to struggle under congressional requirements. For instance, the Paperwork Reduction Act requires that all new requests for information from the public go through a lengthy clearance process. The upshot is that it is extremely difficult to ask for public feedback on government processes or websites. In the end, an act intended to protect the public prevents agencies from soliciting the public’s opinion! This and many other counterproductive laws need fixing.

If congressional investigators today went to see such problems firsthand, Congress would feel greater urgency in cutting the red tape that it itself has imposed on agencies. Further, such an investigation could build support for reforming procedural laws, thereby making Congress more receptive for whatever statutory fixes DOGE proposes.

As in the 1880s, top officials in the American government are determined to clean house. If DOGE is to succeed in streamlining and modernizing government, it will need all the help it can get from Congress. From exposing lousy procedures, to uncovering unlawful practices, to making the case for legal reform, congressional investigations can accomplish what Musk’s team cannot. DOGE today has friends in Congress who should learn from Senator Cockrell’s strategy. It worked in the 1880s, and it can work again today.