The Dark Significance of Spring Cleaning

Every March I rid myself of unwanted books. I hate what the ritual means.

Spring has not yet sprung, but in my effort to expunge memories of winter, I have begun my annual effort to sort through the vast trove of books, movies, magazines, and other ephemera that manages to fill every nook and cranny of my house each year.

When I say “every nook and cranny,” please take my words in the manner in which Trump supporters regard the president’s various utterances: seriously but not literally.

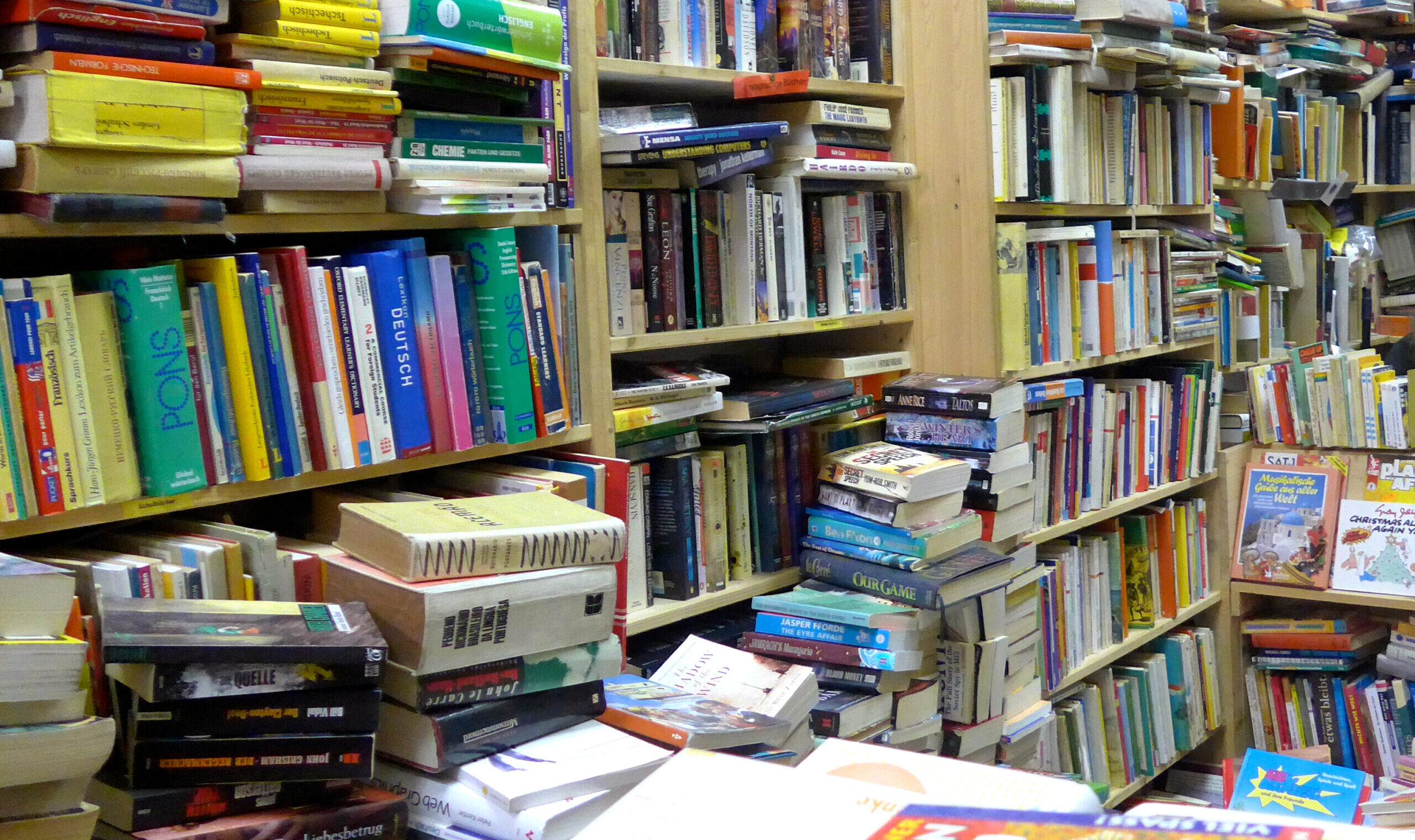

For example, in the comfortable but chaotic environs of my home office, there are books piled wherever they can easily be piled: on my desk, on the floor, on the seat of an armchair originally purchased as a place to read books, not store them. But there they sit: Flannery O’Connor’s Complete Stories, Samuel Lipman’s Arguing for Music, Arguing for Culture, a biography of Orson Welles. Admittedly, it’s a fairly random assortment, but what heap of books wouldn’t be? Besides, such heaps have a way of reassembling, as Shirley Jackson knew when she wrote about spring-cleaning her toy-infested house in Life Among the Savages: “It turns out that although we can live agreeably without the little wheels off things, new little wheels turn up almost immediately.”

Also in my office are several tall bookcases, but their imposing height did not discourage me from forming stacks of oversized books atop them. Let us hope I have no imminent need to reference Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science-Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The Complete Lyrics of Oscar Hammerstein II, nor a compendium of dance reviews from The New York Times—since I am not presently confident I could get at any of them without inducing injury.

Perhaps the accumulation of books in the workspace of a writer is pardonable, but that does not account for the rest of my house. Just across from my office, near the entryway, stands a slender, Shaker-style cabinet constructed in sturdy maple and painted in a pleasant shade of green—a striking piece that had been custom-made by a fine furniture-maker in Connecticut. One would assume that such a prized possession would house something valuable, but when I open its long, narrow doors, I find merely further evidence of my wasteful acquisitiveness: books of insufficient personal or sentimental value to keep on my actual bookcases, galley copies of books I reviewed an unknown number of months or years ago, and complimentary copies of magazines to which I contributed. What would the Shakers have made of using such valuable space for what can only be described as overflow?

Happily, the weariness with which I regard this accumulation of various forms of media is equaled by the pleasure I take in culling it each spring. It’s as if the changing sunlight this time of year casts fresh light on the immoderate carelessness of my coming into possession of so many things. I ask myself: What prompted me to buy a book on sailing? Did I really need to have a 4K edition of Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much when I already owned the DVD? Why did I think I would have time to read (and presumably write an article about) the speeches of Adlai Stevenson? After all, I am not and never have been madly for Adlai.

So, with a sense of discernment I lack the rest of the year, I proceed from room to room keeping an eye out for that which can be tossed out, given to others, or sold for meager profit (more on that in a moment). I take the greatest pleasure in ridding myself of review copies of books whose usefulness has expired upon the writing and filing of my review. What could be more invigorating than throwing Anthony Fauci’s memoir—reviewed in these very pages!—into the garbage bin? I also enjoy refining and reducing the redundancies of my trove of movies. Having been profligate enough to acquire the 4K edition of The Man Who Knew Too Much, I reckon that the least I can do is get rid of the DVD.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

At some point during this process, I might determine that some of my soon-to-be-discarded books or movies could be worth, if not actual money, then at least some pocket change. Thus I make my near-annual expedition to my local Half Price Books, which will evaluate their customers’ printed matter and physical media and make an offer to buy such goods. After depositing my sack of no-longer-needed paperbacks and DVDs with the clerk, I wait and wonder: will the money I receive for this flotsam and jetsam be enough to buy a night out at Wendy’s?

There is something humbling about spending time in the stacks of Half Price Books. The store is packed with steeply discounted books that had once been best-sellers—among contemporary authors, Stephen King always seems to me to be overrepresented among their featured authors—as well as those that struggled to find readers even when they were new and shiny. Half Price Books is a great equalizer: Whether a book was a hit or a miss, this is the purgatory to which it is consigned—lonely, battered, cast aside by its original owner, waiting, perhaps forever, for a new owner unwilling to buy it at full price. The movie section at the store is even more depressing: Imagine being (say) Harrison Ford and stumbling into a Half Price Books only to find multiple copies of The Fugitive whose owners found the movie so expendable, so unworthy of one more viewing, that they turned it in for a couple of bucks.

Perhaps what bothers me the most is the knowledge that my words are expendable, too. If Mark Twain, Graham Greene, and Walker Percy end up in Half Price Books, where does that leave me? The column you are reading exists only in digital form, but if it was contained within our print magazine, or collected in a book of essays (The Wit and Wisdom of Peter Tonguette, anyone?), tell me that you could guarantee you wouldn’t trade it in during your next round of spring-cleaning. I love getting rid of some of the books and movies that clutter my house, but I hate what it means.