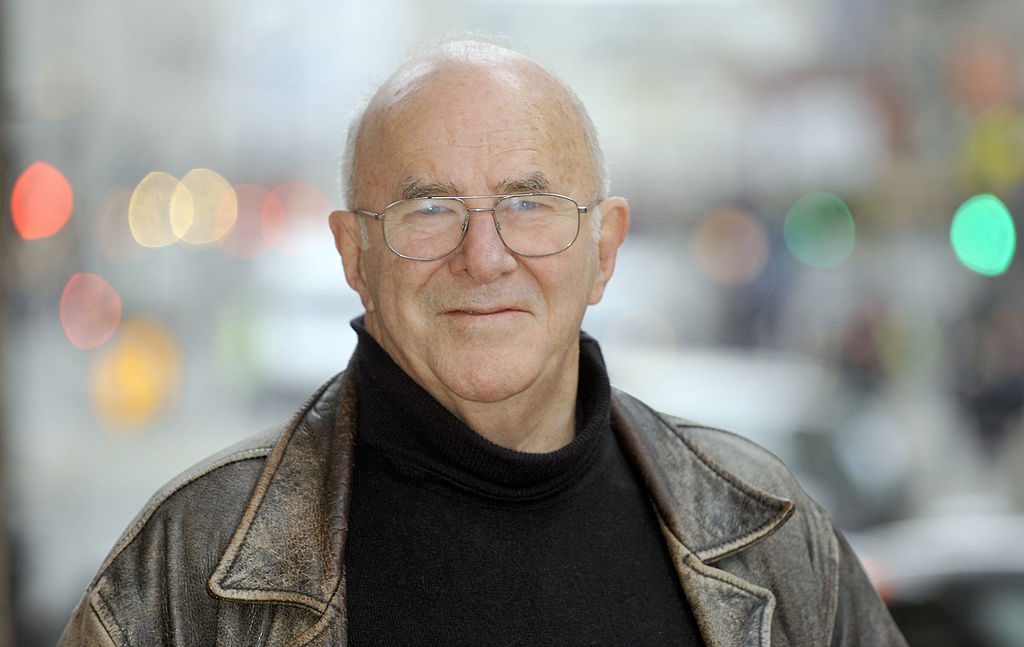

The Accomplishment of Clive James

Clive James died in 2019. Because of his television writing, he is sometimes seen as “a brilliant lightweight who never quite fulfilled his dazzling potential,” Ian Shircore writes in Quadrant. He was no lightweight:

By common consent, he was a better critic than poet. But he was a great critic and, at his best, a very considerable poet.

A year ago, in a shrewd obituary piece for Quadrant, Stephen McInerney argued that what the poetry needed now was a fierce, discriminating editor who would sift through Clive’s 300 poems and sort out the single volume of twenty unassailably brilliant gems that would establish his poetic reputation for the ages. McInerney was right. There are scores of lines where the audacious phrasemaking creates moments of beauty and wonder, but they are followed, every now and then, by the thud of small banalities and awkward discords.

This deafness to his own bum notes is odd in a writer with such critical skills and such a passionate concern for the sounds, senses, rhythms, associations and etymologies of our mongrel tongue’s vast lexicon. But the truth is that Clive, like all truly creative writers, wrote largely by instinct.

Images like the ‘brown condom full of walnuts’ and the ‘haunted fish tank’ arrived fully formed, out of nowhere. There might be some checking afterwards—Does this mean what I want it to mean? Are there unfortunate jingles or echoes of something else? Can I push the idea a step further?—but these coinages were not consciously pieced together from the building blocks of language. That’s not to say that he didn’t work hard and methodically to shape and refine what he called his ‘zingers’. But the initial, inspired impulse was almost always a bolt from the blue—and the bolt sometimes misfired.”

In other news: Lauren Oyler has made a name for herself as a “hard-to-please literary critic.” In February, she will publish her first novel. Will it be any good? I’m including this item for its news only, not its style. Sometimes it seems that American literary life has become merely performative, and Oyler comes across here as playing a role she has created for herself. “I exist in a very dynamic version of the blasé attitude,” she says at one point. Who cares?

A dinosaur skeleton in Argentina may be the largest ever discovered. “The skeleton is still far from complete but paleontologists say what they’ve found suggests the dinosaur may be more than 120 feet long.”

Elena Ferrante’s frantumaglia: “In writing this malady of Lila’s into the Neapolitan quartet, Ferrante made explicit a theme that had appeared more sotto voce in her earlier fiction. While secretive about her identity, the pseudonymous Ferrante has been voluble about her work in interviews and letters, and has helpfully indicated her deepest preoccupations, which she summarizes with the term frantumaglia—another version of ‘dissolving boundaries.’ She claims that frantumaglia is a word in Neapolitan dialect that her mother employed ‘to describe how she felt when she was racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart. She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments…. It was the word for a disquiet not otherwise definable… the source of all suffering not traceable to a single obvious cause.’ This definition appears in a collection of Ferrante’s interviews and correspondence titled, in fact, Frantumaglia. It appeared in Italian after the publication of Ferrante’s first two novels, was later expanded, and in 2016 was translated into English with added material covering the Neapolitan quartet. Frantumaglia is a wonderfully stimulating book for any writer of fiction, as well as for any reader of Ferrante, and its existence couldn’t make it any clearer that ‘disquiet not otherwise definable’ is the deepest substratum of Ferrante’s fictional project. In one of the selections, in a discussion of Olga’s breakdown in The Days of Abandonment, Ferrante says that frantumaglia is ‘a vortex-like fracturing of material living and dead,’ and adds that she herself sometimes suffers from this ‘illness.’ In another interview, she reports, ‘I know what it means to break apart.’”

The snorkeling philosopher of the mind: “Philosophers of mind, with some notable exceptions, still investigate consciousness from the comfort of their armchairs, occasionally venturing into a neuroscience laboratory. Not so Peter Godfrey-Smith. He does his philosophy in a wet suit. A keen scuba diver and snorkeler, with a passion for marine biology and a deep knowledge of evolutionary theory, this Australian philosopher does much of his thinking underwater on the reefs and open water a few hours’ drive from Sydney. In his previous book Other Minds, he gave us a glimpse of the world of octopuses—short-lived, highly intelligent, soft creatures, that can shapeshift and colour change in an instant, and which display evidence of a very different way of being from ours. Godfrey-Smith believes they have minds, perhaps more than one per animal, perhaps a mind per tentacle, plus a central one. In Metazoa, his aim is far more ambitious, though octupuses get a long chapter here too. He wants to provide a philosophical analysis of the evolution of consciousness, one firmly grounded in close observation of the biology and behaviour of a wide range of different sorts of animals, primarily marine animals, explained through an examination of key phases in the evolution of subjective experience. His is a special and rare kind of attention: informed by scientific research, yet sensitive to what he is seeing, the particularity of the creature in front of him, and what it might imply, always to the fore.”

Dominic Green on the legacy of Phil Spector: “Phil Spector, who died in prison on January 18 from complications of COVID-19, was the very model of the modern music producer, and also a convicted murderer. That, it seems, isn’t a problem. Had Spector opined that there are two genders, or that all lives matter, his music would be off the radio. Instead, he shot Lana Clarkson in the face and we still listen to him. This is as it should be. The artist and the art are only the same in copyright law, and only then for a few decades after the artist’s death. Even during that period of posthumous profit, the music business is notorious for prizing apart the creator and the created. And you enjoy Bernini’s sculptures, even though he sent a servant to slash the face of his unfaithful mistress with a knife. In Spector’s case, we cannot afford to have it any other way.”

Monique Roffey wins Costa book prize for The Mermaid of Black Conch.

Geoff Shullenberger reviews Catherine Liu’s Virtue Hoarders: “Virtue Hoarders is the latest entry in a decadeslong debate. John and Barbara Ehrenreich first proposed the term ‘professional-managerial class’ in the late 1970s to designate a new social class that had emerged in advanced capitalist societies. The class’s role was to oversee, in their words, “the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.” As Liu explains, ‘the Ehrenreichs’ PMC comprises deracinated, credentialed professionals, such as culture industry creatives, journalists, software engineers, scientists, professors, doctors, bankers, and lawyers, who play important managerial roles in large organizations.’ For the Ehrenreichs, ‘professional-managerial class’ was a neutral descriptor, neither celebratory nor condemnatory. This is not the case for Liu, whose polemic, in effect, seeks to vindicate the use of the term as a slur by Sanders fans on Twitter. The book’s main contribution to our understanding of class politics is Liu’s account of ‘virtue hoarding” as the primary mode of the class’s rule. As she explains, ‘Whenever it addresses a political and economic crisis produced by capitalism itself, the PMC reworks political struggles for policy change and redistribution into individual passion plays.’ The politics of virtue-hoarding is anti-universalist: Rather than pursue shared public goods, its function is to fortify the class’s dominant position by morally distinguishing it from the underclass.”

Photo: Cathédrale Saint-Lizier

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.