Marillion: Prog-Rock’s Bards of Alienation

“The Cold War is done, but those bastards will find us another one.”

This cry might have come from any current reader of The American Conservative alive in the early 1990s—well, maybe without the bastard part. But still, an anguished expression from Russell Kirk or Pat Buchanan? Why not? After all, as TAC editor Bob Merry recently and wisely noted, so many so-called conservatives of the early 1990s “kicked Reagan to the curb” the moment they inherited the Republican Party. And it seems they kept kicking, mutating a military that came into existence solely to defeat the Soviets into a world peace-keeping force, a new Delian League. The bastards did find us another one.

And then: “They’re here to protect us, don’t you know. So get used to it. Get used to it.”

James Bovard or Virginia Postrel? Or some other grand libertarian of a quarter of a century ago? Why not?

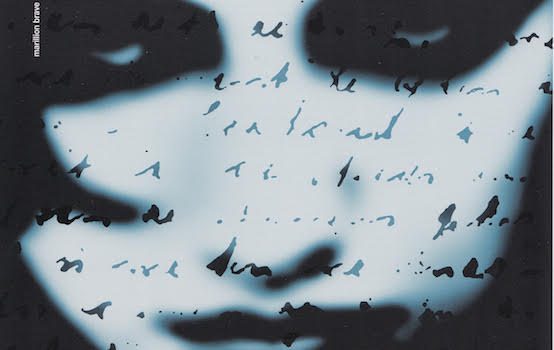

Actually, the words are prog rock lyrics from Marillion’s album Brave (1994).

Taking its name from The Silmarillion, the 1977 book released by the Tolkien Estate, Marillion formed in 1978 and released its first album, A Script for a Jester’s Tear, in 1983. With their third album, Misplaced Childhood, they hit it big as the name “Kayleigh” became a repeated word on MTV and all across European radio. In his excellent book Citizens of Hope and Glory, Stephen Lambe explains: “‘Kayleigh’ penetrated the UK public consciousness like no other song in Progressive Rock with the exception of ‘Dust in the Wind,’ which had done pretty much the same thing for Kansas in the USA in 1977.”

Indeed, the name Kayleigh—in a variety of spellings—became an important and trending name for girls throughout the English-speaking world.

“Fish” was none other than the charismatic and Goliath-sized Scottish lead singer of the band, Derek Dick. After one more album, Dick left, and Marillion hired Steve “h” Hogarth to take over lead vocals. To this day, the decision of the band to replace Fish rather than call it the end has deeply divided Marillion fans. Where Fish was clever and staccato, Hogarth is romantic and suave, bringing a fundamentally different sound.

With Hogarth, the band wrote and recorded 1989’s Season’s End and 1991’s Holiday in Eden. By corporate standards, the albums sold relatively well, each reaching number seven in the United Kingdom. Hoping to get the band to release another album that would sell as well as Misplaced Childhood, EMI’s delegate to the band told them: “Look what you guys need to do is to make a quick, sharp, surefire album, and, you know, get back to basics,” according to bassist Pete Trawavas. By “back to basics,” EMI’s man surely meant to produce another “Kayleigh” and make a huge profit.

Though now gone as an independent label, EMI, it should be remembered, was a major label in the 1960s through the 1990s, having made its fortune with artists such as The Beatles, Queen, Iron Maiden, Elvis Costello, R.E.M, The Smiths, Kate Bush, and Pink Floyd. It had, however, already revealed its true colors in 1988 when it allowed Mark Hollis to make arguably the finest album of the rock era, Spirit of Eden by Talk Talk. A commercial failure but a fan and critic favorite over the past 30 years, Spirit of Eden took 16 months to make, and EMI initially lost a considerable sum. The album has, however, transcended everything, including its label and its band. With its airy atmospherics, its silky flow, and its religious and sacramental lyrics, Spirit of Eden became known simply as the first “post-rock” album, breaking every genre and subgenre then in existence. It has since sold over 500,000 copies.

Marillion chose one of their sound engineers, Dave Meegan, to produce their third album with Hogarth. Having studied with famed producer and musician Trevor Horn (The Buggles, Yes, Seal), Meegan had also worked, perhaps most famously, with U2 on The Joshua Tree (1987) and Rattle and Hum (1988).

Meegan, it turned out, loved the gothic elements of sound, that is, the jagged nature of nature and of music, the uneven and the odd. Setting up their studio in a castle in the southwest of France, Meegan and the band recorded everything: from a fire crackling to random conversations to the air moving through hallways and turrets, all, it seemed, to pick up the random atmospheric of a passing ghost. “The theory was that if we fed all the mics onto tape then we’d pick up any passing ghosts as well. You can’t hear them but I can feel them here and there,” the atheist Hogarth remembered. “Brave is all about the spiritual aspect of life dominated by the non-spiritual, so we filled the songs with as many sounds and pictures as we could dream up—I sent our sound engineer out at dawn one morning to record silence for the beginning of the album!”

EMI’s desire to make a fast pound faltered almost immediately, as Meegan and Marillion began to echo Hollis’s work on Spirit of Eden. As it turned out, Meegan and the band took eight months to write the album and another seven to produce. Certainly, this was no longer normal commercial territory. Even the members of Marillion began to express concern over the time it was taking. But producer Meegan responded: “The way I see it, we could make a masterpiece or we could just make a very average record and you’ve got to decide which one you’d like.” The band chose “masterpiece.”

Inspired—or frightened—by the real-life news story of a young English woman who had been found walking around Severn Bridge unsure of her own identity, history, or age, Hogarth centered the concept of Brave around alienation, a human trapped in an overwhelmingly mechanistic and progressive world:

The babble of the family

And the dumb TV

Roar of the traffic and the thunder of jets

Chemicals in the water

Drugs in the food

The heat of the kitchen and the beat of the system

The attitude of authority

The laws and the rules

Hit me square in the face, first morning at school

The heroes and the zeroes

The first love of my life

When to kiss and to kick and to keep your head down

When they’re choosing the sides

I was never any good at it

I was terrified most of the time

I never got over it

I got used to it

Though many artists have depicted alienation, no one has done it quite as well as Hogarth and Marillion. From the moment the album begins to its final second 72 minutes later, Brave captivates its listeners.

WidowQuinn/Flickr

As with Hollis’s Spirit of Eden, Brave never lived up to the hopes that EMI had invested in it. Marillion would only write one more album for the label, its phenomenal 1995 release Afraid of Sunlight. And despite the time and effort that went into Brave, it never caught on the way Misplaced Childhood had. In his diary entry dated March 29, 1994, Hogarth expressed his frustration:

The general reaction to Brave can only be described as euphoric. Why does media and radio despise us? I guess you either love or loathe Marillion…. Conversion is a long and quantum jump. Our music seems to be behind a locked door. It’s fun in the room if you find the key!

Following Afraid of Sunlight, Marillion decided to leave not just EMI but the entire corporate rock world behind. Amazingly, the band charted its own course, and even more amazingly, it succeeded. As Hogarth told Prog magazine in 2016, commemorating their 20th year of independence, labels are “not doing it because they love you. If they’re really honest, they’re not even doing it because they’re excited about the music.”

In true entrepreneurial form, the band made its 1999 album marillion.com available to their subscribers on the website of the same name. It proved a huge success. A year later, the band innovated again, offering the very first crowdfunded album in the history of rock. Since then, the band has made one success after another. Though they’ve never sold in the numbers they did in the 1980s, they have, perhaps, the most loyal fan base in the rock world today. Those who love Marillion—such as Gianna Englert, a young political theorist at Southern Methodist University; famous Lutheran organist and music theorist Rick Krueger; and the venerable libertarian Tom Woods—follow the band through every tour and keep up with its every nuance.

Whatever Hogarth’s worries in 1994, he and Marillion have transcended their critics as well as themselves in almost every way that matters. When the album came out, one of its most ardent supporters was South African filmmaker Richard Stanley, who retold the story of Brave in an art film of the same title that year, using the album as a soundtrack. Though the ending of the film is, arguably, more dour than the end of the album, the film not only does justice to the album, it does justice to the art.

Twenty-four years later, the album remains as vibrant as ever. Just this year, audiophile and musician Steven Wilson remixed and re-released Marillion’s Brave. The deluxe, 60-page hardback edition of the re-release comes with the original mix of the album, the 2018 mix of the album, two DVDs of a 1994 concert, and a Blu-ray with the full Wilson mix in 24-bit, promo films, a bonus track, and a 70-minute documentary.

Music journalist Stephen Humphries (Christian Science Monitor, Prog, Boston Globe, American Way) explains the brilliance of Brave best:

Hogarth, an uncommonly emotionally honest singer, turns one person’s search for connection, meaning, and redemption into something that is universal to the listener. I often tell people that Marillion reaches emotional and musical planes that most other bands don’t know exist. Brave exemplifies those qualities. The beauty of Steven Wilson’s remix is how it creates even greater clarity and space in the instruments so that Steve Hogarth’s voice can seep through to the listener’s soul.

Looking back over the past three decades, it’s rather clear that the bastards did indeed bring us another one, and they do simply want us to just get used to it. Yet in large ways and small ways, we normal folks keep fighting back—through truth, beauty, and goodness.

This piece benefitted immensely from the writings of Paul Stump, Phill Brown, Roie Avin, Stephen Lambe, Stephen Humphries, Rich Wilson, and Jerry Ewing.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-in-residence. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.