Make America Grunge Again

Grunge identified many of America’s problems, even if it couldn’t offer solutions.

Twenty-five years ago, in an act of apathetic surrender to mediocrity, rock and roll announced its precipitous decline into irrelevance. The event that marked rock’s demise was Billboard’s 1998 decision to name Creed—known for such immediately overplayed, insufferable singles as "My Own Prison," “Higher,” and “With Arms Wide Open”—as their “Rock Artist of the Year.” It was as if the musical powers that be were implicitly acknowledging rock and roll no longer had anything novel or important to say.

Since that fateful year, has it? The most popular bands of this century include Coldplay, Maroon 5, Linkin Park, the White Stripes, and the Killers. Sure, some of these bands have been talented, selling millions of records with songs that were sometimes creative, often enjoyable, and usually catchy. So catchy their art is quickly appropriated by advertisers to sell every product under the sun.

But who would accuse the favored bands of the last quarter-century of being truly innovative, of carving out new, uncharted territory? Most of them seem as artificial and intentionally mainstream as The Monkees. Does Maroon 5 even play their own instruments? And as much as I adore the Black Keys, a band that in its early years perfectly represented the frustrated, post-industrial tenor of Rust Belt Ohio, they are at their best when retreading, or modifying and improving, paths made by earlier blues rock musicians many years before. And they are self-aware and self-deprecating enough to make light of their wealth and mainstream fame.

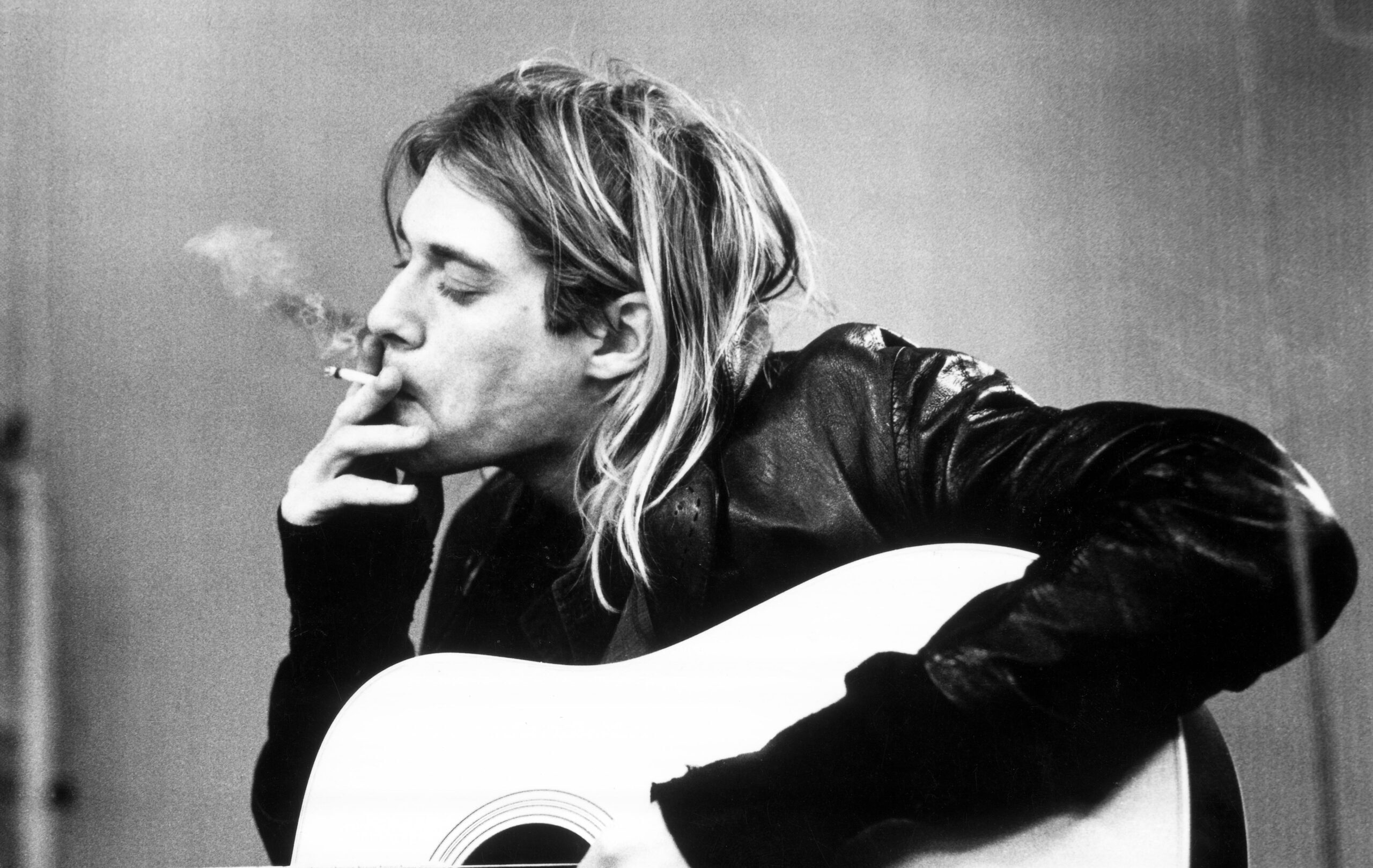

But Creed, like many of the other post-grunge poser bands of the late 1990s—Nickelback, Puddle of Mudd, Staind—were simply jejune copycats of perhaps the last legitimately novel rock movement, the authentically counter-cultural grunge bands of the late 1980s and early 1990s, most of whom hailed from the Pacific Northwest. Pace Adam Levine or Chris Martin, could anyone imagine the subversive, spotlight-averse Kurt Cobain doing a commercial for Target or T-Mobile? Hell, before anyone outside a small town in Pennsylvania knew the name Taylor Swift, Pearl Jam sued and tried to tour outside of Ticketmaster in 1995; the company responded by organizing a boycott of the band and making veiled threats to promoters.

What made the greatest grunge acts—in all their raw angst and anti-establishment cynicism—seem somehow fresh, even unprecedented in their entrancing employment of distorted electric guitar and angry, introspective lyrics? Many have argued it was Seattle’s isolation from the rest of the music industry that helped foster grunge’s peculiar character. Jonathan Poneman of Sub Pop, a Seattle-based independent record, has said: “Seattle was a perfect example of a secondary city with an active music scene that was completely ignored by an American media fixated on Los Angeles and New York."

Though we now think of the Seattle area—home to Starbucks, Microsoft, and Amazon—as the embodiment of the globalist, technocratic class, it was once a remote, working-class city, populated by Boeing union workers, loggers and fishermen. Sub Pop co-founder Bruce Pavitt called Seattle "very working class," which seeped into the grunge aesthetic, whose musicians wore flannel and thrift store truckers' hats, and played pawnshop guitars. That certainly was the case for some of grunge’s biggest names. When Nirvana’s Nevermind hit number one in the U.S. charts in 1992, lead singer Kurt Cobain, the son of a waitress and an auto mechanic, was living in a car. Jerry Cantrell, lead guitarist of Alice in Chains, grew up on welfare and food stamps in Tacoma, Washington.

One of the most curious things about the grunge phenomenon is that a musical genre defined by its outspoken rebelliousness and refusal to conform occurred simultaneously to perhaps America’s greatest geopolitical victory: the defeat of global communism. Nirvana released its first album, Bleach, in 1989, the year the Berlin Wall fell. Alice in Chains signed with Columbia Records that same year. In 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, Pearl Jam released Ten, which would in time certify thirteen times platinum; Nirvana’s Nevermind was selling 400,000 copies a week by December of that year.

Why was it that at the very moment when America was at its most economically and militarily powerful, when it alone carried the mantle of global superpower, when Francis Fukuyama was championing “The End of History,” that grunge, in all of its skepticism towards patriotic trust in democracy, capitalism, and God, became popular? Perhaps because the genre’s spokesmen were raised in an America that felt not the blessings, but the curses of an ever more liberalized America and a “smaller earth.” Between 1980 and 1985, employment of operators, fabricators, and laborers fell almost 16 percent, a loss of millions of jobs. The technocratic class waxed eloquent over free trade and the sexual revolution; the working class suffered the disastrous consequences.

Indeed, one of the traits shared by most of the well-known figures of the grunge movement was an intimate familiarity with divorce. Cobain, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder, Alice in Chains’ Layne Staley and Jerry Cantrell, Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, and Stone Temple Pilots’ Scott Weiland were all products of broken homes. All born in the 1960s, they were the first generational casualties of the sexual revolution and its permissiveness towards divorce, remarriage, and cohabitation. Cantrell once spoke of his mother leaving his father: “He didn’t walk out on us. We left him. It was an environment that wasn’t good for anyone, so we took off to live with my grandmother in Washington.” Cobain in a 1993 interview admitted that he yearned for a "typical family...I wanted that security, so I resented my parents for quite a few years because of that."

This, little surprise, led to frustrated, dark lyrics that often centered on—as grunge’s Wikipedia article correctly describes it—“social alienation, self-doubt, abuse, neglect, betrayal, social and emotional isolation, addiction, psychological trauma and a desire for freedom.” The titles of some of the best songs of the genre say it all: Soundgarden’s “Fell On Black Days”; Alice in Chains’ “Down in a Hole”; Pearl Jam’s “Black”; Nirvana’s cover of "Jesus Doesn't Want Me for a Sunbeam.”

That antipathy towards God was shared by many of the leading lights of grunge. For a time placed with pious foster parents, Cobain briefly became a devout Christian before renouncing the faith altogether and mocking it such as in the video for “Heart-Shaped Box.” Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell attended Catholic grade school, but his mother pulled him out because he was about to be expelled. “With a religion like that, it's not designed for anyone to question,” he later claimed. In a 2009 interview with the Guardian, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder—who ridiculed Christian faith in songs such as “Glorified G” and “Do the Evolution,” declared: “So much in America is based on religious fundamentalist Christianity. Grow up! This is the modern world!" Staley said much the same in a 1991 interview: "I have a fascination with how brainwashed people get with religion and how they'll give up their money, their time and their whole life for a cause that they're sure is right, but I'm sure is wrong.”

Why were grunge artists so antagonistic towards Christianity? Part of the answer likely lies in a distrust of authority stemming from the broken homes that defined their childhood. Yet also, it seems, many of them perceived hypocrisy in the unholy alliance between public Christianity and unchecked capitalism, often manifested during their upbringings in the prosperity gospel of corrupt televangelists. During a 1993 interview, Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic jokingly mimicked a street evangelist he encountered whose preaching was tainted by materialist themes: “When I die I will go to heaven and the streets will be paved with gold…. You will have a Pontiac in your garage. You will all look like Farrah Fawcett-Majors, regardless of gender.”

That hostility towards authority took other forms, as well, and some of these curiously rhyme with contemporary populist, conservative narratives about elite America. Novoselic in that same 1993 interview criticized an article about Nirvana which appeared in Newsweek—“an establishment magazine,” in his words—which he explained was largely inaccurate in its portrayal of the band. “Then I started flipping through other stories about the Middle East, and whatever, and I started thinking, how much credibility do these stories have?”

Moreover, it was grunge’s birthplace, Seattle, which in 1999 would witness violent riots against the World Trade Organization that featured a coalition of "teamsters and turtles,” the latter a nickname for environmentalists. Despite opposition to free trade from some figures on the right (such as TAC’s founder Pat Buchanan) and many on the left, the leadership of both parties in the 1990s—as well as most of the establishment—endorsed open markets. In response to the anti-WTO demonstrations, the New York Times wrote an (erroneous) story claiming protestors threw Molotov cocktails at police, while CNN, ABC, CBS, and NBC sought to portray demonstrators as violent extremists. And yet the “Battle in Seattle” seems now to have presaged a stronger anti-globalist, anti-free-trade movement in America. Protestors even created a spoof newspaper claiming Boeing was relocating overseas.

That anti-establishment mentality manifested itself in other humorous ways. The New York Times in November 1992 published a full-page story on grunge and its new “lexicon,” which included supposedly sub-culture slang words like “bloated” (drunk), “cob nobbler” (loser), and “swingin' on the flippity-flop” (hanging out). Unbeknownst to the NYT journalist, Rick Marin, the whole thing was a hoax concocted by Megan Jasper of Caroline Records, whom Marin had interviewed. Jasper later admitted to Thomas Frank at The Baffler her fabrication. Frank publicly gloated: "When The Newspaper of Record goes searching for the Next Big Thing and the Next Big Thing piddles on its leg, we think that's funny."

Of course, grunge wasn’t just about sticking it to the man. The music was often arresting in its tragicness, loudness, and dissonant harmonies. Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil wrote many songs in septuple meter in 7/4 time, such as the band’s hit “Spoonman,” while lead singer Cornell’s staggering vocals on such songs as “Pretty Noose,” overwhelmed audiences. I still remember that first electrifying experience of hearing Cornell sing “Burden In My Hand.” Pearl Jam could craft both speedy rock tracks such as “Even Flow” or “Corduroy,” and tear-inducing sentimental ballads like “Yellow Ledbetter” and “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town.”

And, obviously, they could offer some of the best live rock shows ever performed, among which Nirvana’s 1994 MTV Unplugged performance is unparalleled. Uncharacteristically recorded in a single take in November 1993, the concert featured staples such as “Come As You Are” and “All Apologies,” but also hauntingly mesmerizing covers of David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World,” and Lead Belly’s “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” Almost thirty years after first hearing it, the record still gives chills. Not released until almost six months after Cobain’s death in April 1994, the album debuted at number one and sold almost seven million copies.

Eddie Vedder and Kurt Cobain were quite capable lyricists who painted scenes, however disturbing, that came to life through their ability to evoke pathos. Vedder, ever the dramatist, sings in “Black” of lost romance:

And now my bitter hands Cradle broken glass Of what was everything All the pictures have All been washed in black Tattooed everything All the love gone bad Turned my world to black Tattooed all I see All that I am All that I'll be, yeah

Cobain’s lyrics were typically more blunt and biting in their impiety. In “Lithium,” he sings:

I’m so happy, ’cause today I’ve found my friends They’re in my head I’m so ugly, that’s okay, ’cause so are you We’ve broke our mirrors Sunday morning, is every day for all I care And I’m not scared Light my candles, in a daze, ’cause I’ve found God

This brazen negativity was often pilloried. In one memorable Simpsons episode, Homer meets the grunge band (or at least grunge adjacent) Smashing Pumpkins. Homer declares: “You know my kids think you're the greatest, and thanks to your gloomy music they've finally stopped dreaming of a future I can't possibly provide.” Lead singer Billy Corgan responds: “Well, we try to make a difference.”

That is funny, but not entirely fair to grunge, which spoke with an unprecedented degree of authenticity and vulnerability. Alice in Chains’ hit “Rooster,” written by Jerry Cantrell, is a reflection on his father, a Vietnam War veteran who served in the 101st Airborne Division. The lyrics include this bracing line: “Walkin' tall machine gun man; They spit on me in my homeland.” Would any band of the `60s have sung so sympathetically of what working class draftees faced in the jungles of Southeast Asia? Pearl Jam in turn sang about political dissidents, kids shooting themselves in the classroom, and women trapped in bad relationships.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

In that respect (and many others), grunge represented an aggressive repudiation of the superficial, chauvinist, hair bands of the 1980s. Kurt Cobain was quite vocal in his animus towards bands like Poison and Bon Jovi, even if he acknowledged that following Nevermind’s success Nirvana had also become “mainstream.” Perhaps that deep anti-establishment ethos explains why grunge’s day in the sun was so abbreviated: Once its representatives had become, however briefly, household-name millionaires performing sell-out stadium-seating concerts, their raison d'être, let alone their credibility, was undermined. Cobain shot himself in 1994, and Staley overdosed on the same day eight years later; Scott Weiland overdosed in 2015, and Cornell hanged himself in 2017; Screaming Trees’ Mark Lanegan, who struggled with alcoholism and drug addiction throughout his life, died just last year at age fifty-seven.

“I have seen all things that are done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and a chase after wind,” wrote Qoheleth in the first chapter of Ecclesiastes. The grunge generation—who amid a time of remarkable American economic prosperity were already suffering the destabilizing, atomizing consequences of the sexual revolution and globalism—felt that biblical sentiment deeply. Indeed, grunge may very well have been the last legitimate musical protest against a deracinated establishment and its bourgeois condescension towards those on the periphery. Music critic Dave Whitaker in 2011 declared grunge “the last American musical revolution.” And though grunge artists would just as likely repudiate a connection to the MAGA movement as embrace it, there is a real sense in which their stories and protests foreshadowed those of blue collar voters realigning with an increasingly protectionist Republican Party.

Indicting the establishment for its exploitative behaviors and hypocrisy is one thing. Offering an alternative, and being willing to lead such a project, is quite another—an enterprise that requires, among other things, hope, charity, and even faith. I would argue that at least partly explains why grunge so quickly petered out, subsumed, as it were, by larger corporatist forces who exploited their genre to make millions via inferior imitations. Grunge could identify the problem, but, because it had rejected not only consumerism, corporatism, and soulless careers in cubicles, but also the vivifying, redemptive power of religious faith, its ability to propose solutions, let alone survive, was meager. There’s a lesson there in our time of renewed populist fervor. Otherwise our future may be as impoverished and banal as Creed.