Laboring in Vain

The modern city is in most ways a failure.

Unless the Lord has built the house, its builders have laboured in vain. Unless the Lord guards the city, the watchman watches in vain. Psalm 127:1

Arthur Trystan Edwards once pleaded for good manners in architecture. He later suggested that Modernism be in partnership with tradition. But the Modern Movement in architecture had rejected such a partnership; it did not value "traditional" architecture at all, or even recognize it had any merits. Indeed, Edwards noted that Modernists welcomed the demolition of old buildings in the expectation that, in their stead, room might be found for new modernist-designed buildings.

It was actually worse than that. In the wake of 1945, most local authorities, certainly in the United Kingdom, had planning offices headed by Modernist architect-planners, who possessed considerable powers. Nicholas Taylor perceptively described such commonplace conditions as municipal fascism. The designers and authorities responsible, however, were immune from criticism. Modernist housing dogma prevailed, even when most people seemed to want to live in low-rise, low-density suburbs.

Although the mechanisms differed, the results of widespread adoption of Modernist architecture and planning were similar across the globe. In the U.S., Modernism impoverished American towns and destroyed age-old social arrangements. In several countries, the tenets of Modernism were promoted by German émigrés. Soon, they dominated urban planning.

Seeing the possibilities for cost savings, property developers, industrialists, corporations, architects, and politicians backed Modernism. High-rise buildings and super-highways arose everywhere. No one could question Modernist orthodoxy for fear of being denounced as "conservative," "Fascist," or, worse, "bourgeois." It was later recognized after years of denial that something had gone wrong, but not before catastrophic destruction had been inflicted on urban fabric and urban civilization.

Modernism is predicated on the belief that utility alone is beautiful. That belief is partly derived from the writings of the Gothic Revivalist A.W.N. Pugin, but has been stripped of its religious connotations. While it is certainly true that something that is useful can be beautiful, its beauty is accidental, uncertain, and dependent on other factors. Architecture is not just about service or utility. To be architecture at all, it should have an effect on the human mind, spirit, and sensibilities.

Utility and beauty do not always lie easily in the same bed.

The Psalm at the head of this essay is given in the Authorized Version of the Anglican Church as "Except the Lord build the house: their labour is but lost that build it. Except the Lord keep the city: the watchman waketh but in vain." Sir Patrick Geddes paraphrased this verse, saying that unless the house is built with an ideal and the city also, the labor of creating them is in vain.

Much architectural and urban development since 1945 has been based on data, expediency, cost-benefit analyses, space and light standards, and way-off-the-mark traffic projections. In other words, design considerations have been confined to the Modernist vocabulary. But lavatories, window areas, and cubic capacity are insufficient on their own to create an environment uplifting to the human spirit.

Modernism's failure to acknowledge that fact is why the movement has ruined cities. A city should aspire to more than mere function. It should strive to be, in some sense, a work of art. Modernist architecture strips the spiritual, uplifting aspects of the built environment and replaces them with statistics, propaganda, and advertising. It contributes to the lost understanding of a city's symbolic worth. Its exaltation of empirical data has created enormous dangers.

The empiricist, viewing a medieval mappa mundi for the first time, might be tempted to be amused. From his or her level of supposed superiority, the measurable and obvious faults in the drawings can be identified. But the symbolic and spiritual significance of such a document will be elusive to him. He will not see it in the same light as a representation of a labyrinth in a cathedral floor, an ideal-city plan, or an Aztec vision of continents.

By depriving symbols of their reality and meaning, empiricists confuse and impoverish art, painting, sculpture, architecture, and city-building. The Modernists insist that only that which can be seen, measured, and explained in "real" terms will have any use for a society that has jettisoned much of its historical and religious cultural inheritance. But the devaluation of the symbol, and indeed its exclusion from architecture of the Modern Movement, has played an important part in what has turned out to be a disaster for the environment, and therefore for people, too.

The purely functional or empirical city is a dreary place, unrelieved by the finer, unquantifiable aspects that make life rise above the level of the ant-hill. But since so much of contemporary society is ordered around measurable phenomena that can be fed into a data-bank, those things of the spirit and the mind, being unmeasurable, are not included in the final analysis.

Consider hospital design as an example. Architects are not trained to read research papers in biology, chemistry, or physics. They rely on architectural critics, polemicists, theorists, and journalists to direct their views, few, if any, of whom have scientific backgrounds. They rush to produce the next "iconic" structure, which can only be realized with huge amounts of capital and a massive waste of resources. The welfare of patients is not considered, despite research showing that buildings, the environment, and surroundings can affect a person's health. Schools of architecture, influenced by Modernism, train students in hospital design based on formal, stylistic ideas of spaces and materials, despite the empirical evidence accumulating toward a greater understanding of how human beings react physiologically to their surroundings.

This illustrates a missing feature of today's architecture debate: Empathy, and an understanding of how gravity and stability in building design can induce calm and ease in those who have to live with the fruits of an architect's vision.

Just as there are those who criticize modern hospital design, many have reappraised the dominant theories of urban planning and architectural design. Some claim that to be successful, urban space must be a collective work, socially produced—the opposite of mainstream Modernist urban planning, which has been largely based on abstracted knowledge and non-participatory processes. In other words, it does not work if merely imposed as part of some design dogma, which was the endemic problem in Modernist-inspired work, as has been argued by critics such as Alice Coleman and Jane Jacobs.

Architecture depends on uncertainties and contingencies: What architecture is and what architects want it to be are often very different, for architecture has duties to the world and to humanity, to the real world, something often forgotten in the pursuit of Modernist abstractions. That is why the traditional street, the urban space, the very fabric of towns and cities, with all its messy, varied uses, and disparate elements, rarely survived draconian Modernist architectural interventions, which were too tidy and neat for the realities of use.

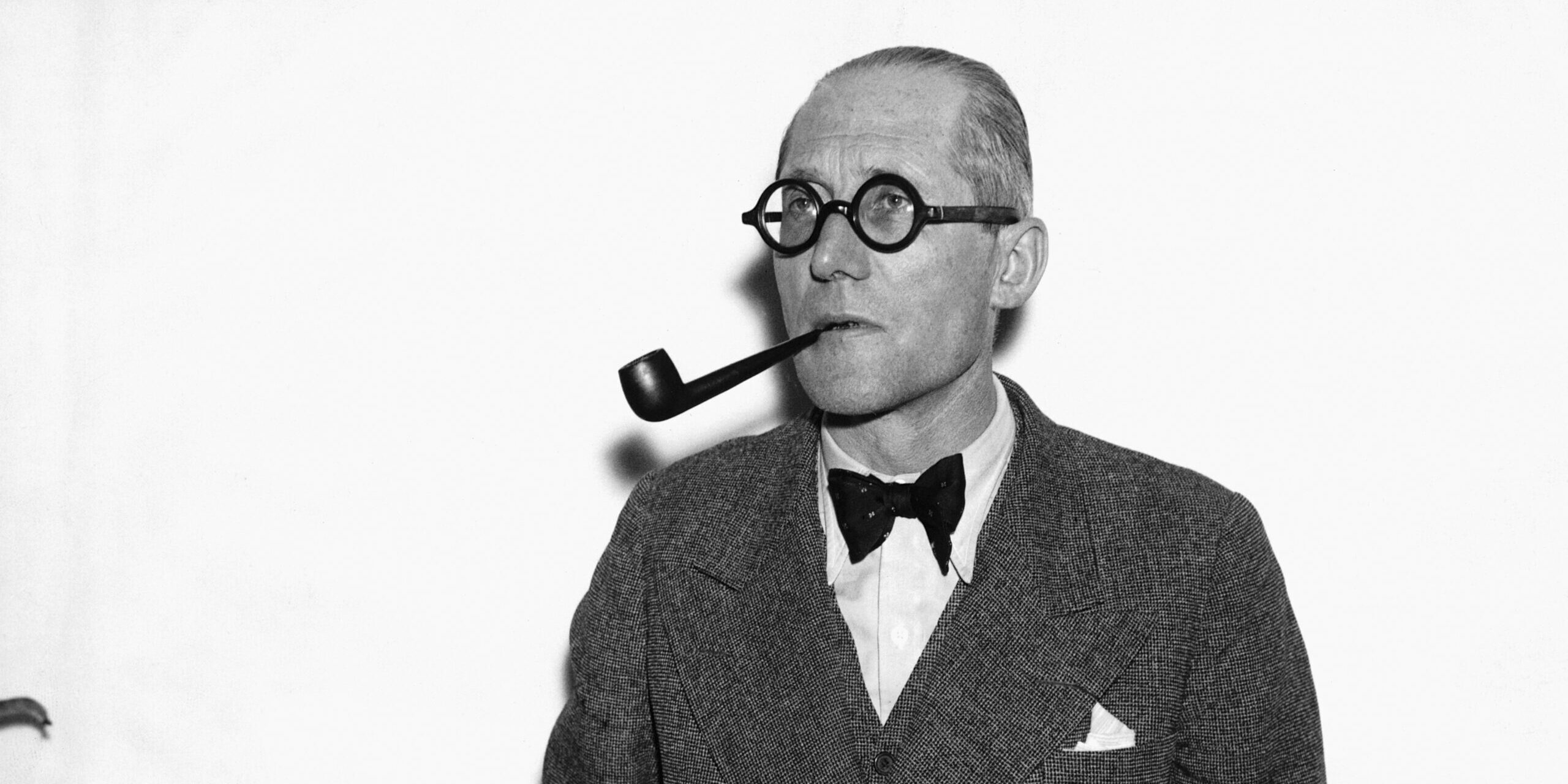

Jacobs was undoubtedly correct in arguing for untidy, mixed-use places that could be lived in, and Coleman’s dissection of what was wrong with Corbusier-inspired developments deserved attention. Both were nevertheless derided by the architectural establishment, which refused to acknowledge the damage it had inflicted on vital urban organisms, many of which became moribund as a result of Modernist interventions.

The modern city is in most ways a failure, and leaves its inhabitants feeling betrayed and without affection for their surroundings. Some commentators have offered prescriptions for the disease, including canalizing youthful energy, and creating a utopia in which work is made, in that ghastly phrase, socially meaningful. These are not cures, for the problem is the dystopian environment that has been inflicted on humanity. It is the built environment that must change, not its unfortunate inhabitants.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Ancient settlements, old-established towns, and cathedral-cities have their raison d’être. Those are among the places still pleasant to visit and inhabit, in which to work and live. But they are becoming fewer in number as more places fall victim to disastrous road proposals, blighting developments, buildings without meaning, and urban spaces that are uninviting, dangerous, and wind-swept.

Squalid environments attract protests and violence. It is not difficult to see why. Perhaps the Psalmist had a point after all.

This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.