‘Knives Out’ America

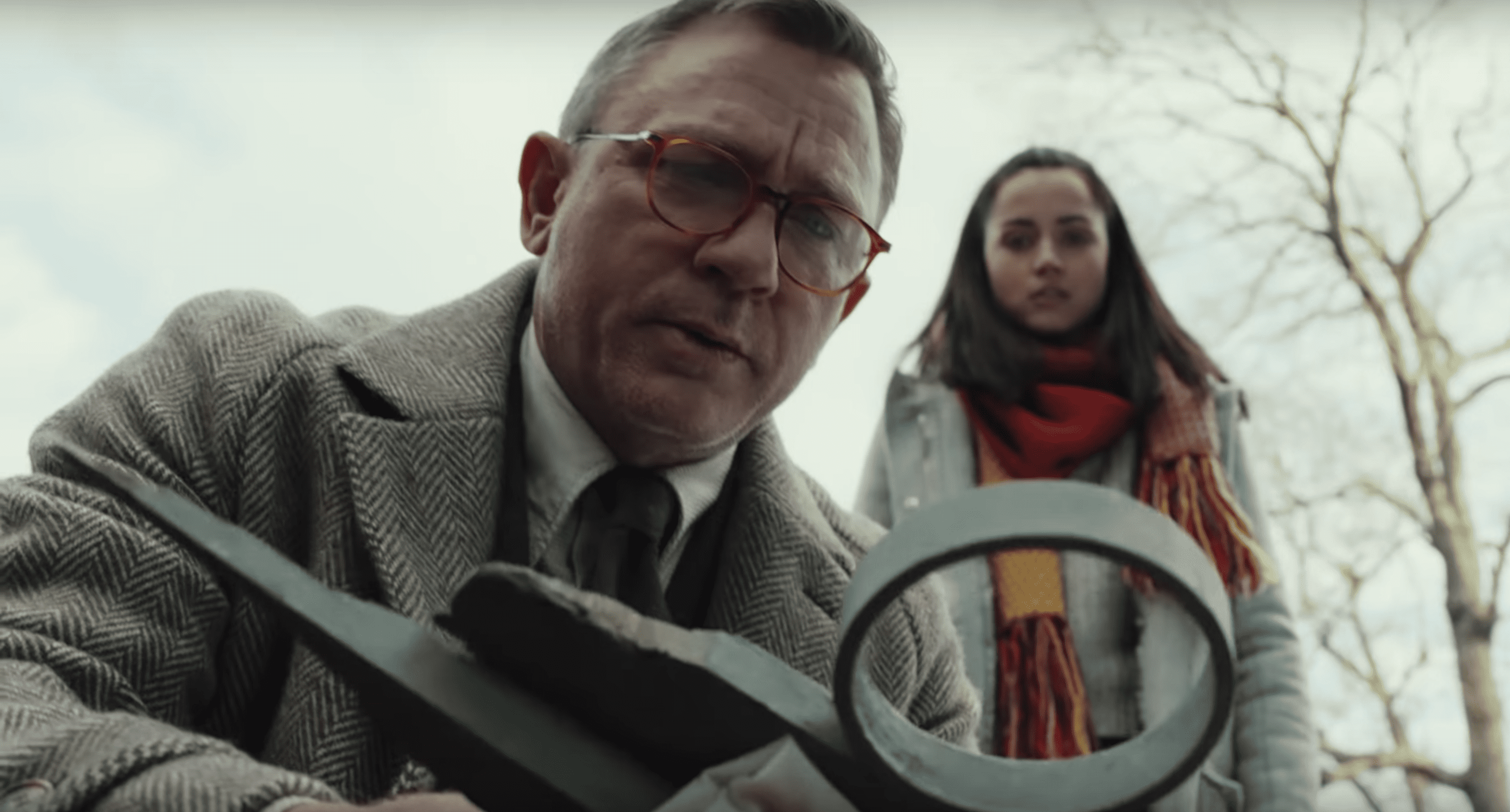

About a third of the way through Rian Johnson’s bloodsport of a film “Knives Out,” the raison d’aitre of a character is revealed: detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) is on the case, because someone gave him an envelope of cash.

Blanc’s compatriots, the dim local authorities, press him further. Why has Blanc, a New Yorker-profiled, celebrity detective, decamped to a local estate—quickly revealed to be a hothouse of psychosis—to investigate a routine death, the suicide of an melancholic old man? Blanc persists: it’s self evident, someone left him an envelope of cash.

It’s a seemingly innocuous moment, but serves to demonstrate the ruling ethic of the age: the primacy of money. No one is exempt, including Craig’s Southern gentleman sleuth. It takes one to know one, as Craig emotionally disembowels a contemptible cast of America’s officially rich.

There’s Jamie Lee Curtis’ portrayal of a self-made daughter of a millionaire. There’s Don Johnson’s portrayal of an aging bad boy who supports legal immigration, mind you, not illegal, and demonstrates that commitment by subjecting the family’s legal immigrant nurse to a vacuous inquisition in front of other party guests (the woman’s family, it turns out, is illegal).

There are new stars Katherine Langford and Jaeden Martell’s portrayals of the Zoomer political abyss: cultural Maoism against the alt-right. The only characters more deformed than the very online duo are the older characters who heedlessly mock their children, never stopping to query why scions of lavish privilege are so miserable, and have drawn such dark conclusions about the future.

And there’s Christopher Plummer’s portrayal of one of the only two characters meant to be sympathetic (Ana de Armas’ nurse being the other). Plummer, having long presided over this abattoir of anxiety, asks a question apparently many fellow Americans have in recent years: why didn’t he try heroin earlier?

The film has clearly struck a nerve: the hyper real story of dying titan of the mystery novel deciding to cut his shameful family out of his will. De Armas’ character is Plummer’s sin-eater, inheriting his fortune after he commits an apparent suicide.

The juxtaposition between De Armas’ striving Latino family and Plummer’s den of WASP rot is obvious. Less apparent: Plummer’s maneuver, like suicide, is ultimately selfish, a cleansing exercise that leaves its purported beneficiary left holding the bag.

Plummer’s family, whose ascent was based on literary wealth, now appears short on creativity and long on destruction. There are dueling reactions to this reality. Michael Shannon plays Plummer’s leech son, whose own career is stillborn, but has become a Machiavellian manager of his father’s legacy. After the will is released, Shannon plunges to depths, callowly threatening the nurse’s family’s immigration status, which of course he had been previously more than happy to overlook.

But the competing interpretation of the last days of this family comes in the form of Chris Evan’s character, named Ransom, who ultimately descends further and more impressively than Shannon, after his life of handsome hedonism is interrupted. Ransom is the only family member sanguine after the will is released. Plummer, in a moment of gene-deep fealty, remarks that the young man is the character most similar to him.

“Knives Out,” an apt title for an America that closes the decade in a cold civil war, shows the limitations of institutions that served the country until recently. What’s the purpose of family in an age of polarity undergirded by money? Should society worship innovation even when it’s stalled? And is it too late to put the knives away?

Blanc, of course, ultimately wraps up the central question of the film. But he answered the easiest one.

Curt Mills is senior writer for The American Conservative.