In Fastest-Growing Texas, Rural Population Is Still Declining

Texas’s growth over the last two decades has been the envy of just about every state in the union. But while that growth has grabbed headlines, parts of Texas have endured some of the steepest population declines anywhere in the country. While that might not be surprising to some who refer to the area as “The Big Empty,” the downfall of communities that dot the area can be shocking to see first hand.

Despite the fact that Texas is the second most populous state in America, it still managed to grow by a staggering 14.1 percent from 2010 to 2018. However, parts of Texas have continued to suffer from population loss, specifically due to rural flight that started back in the 1950s.

It’s a similar story to countless other rural farming communities in America. Modernization and efficiency slowly crept from farm to farm over decades; the changes were like a drop in the bucket to those living through them at any particular moment, but altogether the process looks like a flash flood in certain areas of the country. A select few states haven’t witnessed this effect, but what’s surprising is that America’s fasting growing state has areas that have been hit harder than most others.

In North Texas, you can see the effects as you drive through what’s left of tiny towns like Peacock, Lueders, Clairemont, and Gouldbusk. Except for a handful of homes, they’re essentially all but ghost towns. You may not even notice that you’re driving through what was once a town when you pass places like Medicine Mound or Tuxedo. Even the moderately sized small towns like Coleman, Stamford, Anson, and Sweetwater saw their peak population decades ago.

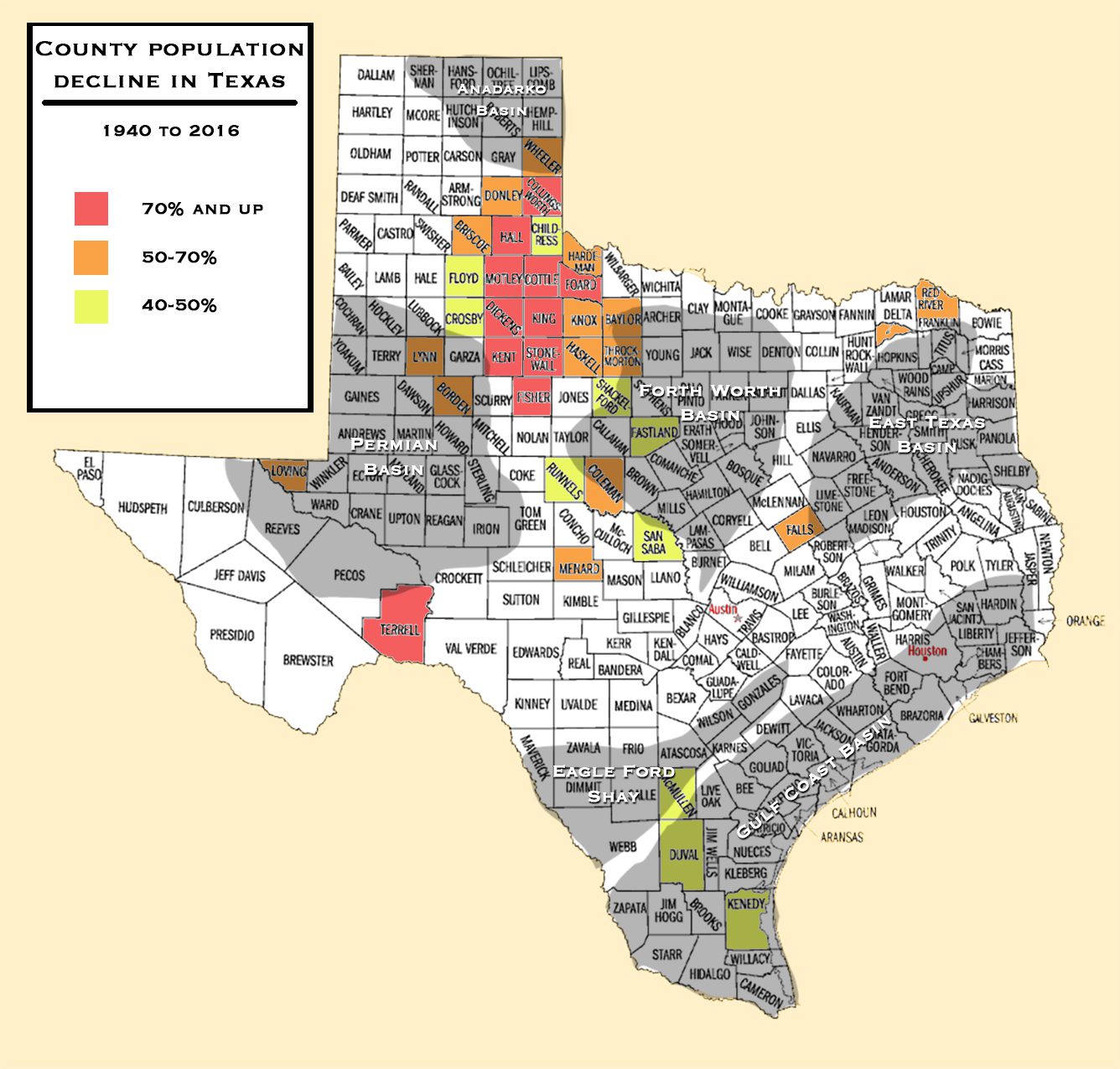

All of this is an odd story to hear coming out of the fastest-growing state. Yet, between North and West Texas alone are 10 counties that have lost over 70 percent of their population since 1940. Even though the pace has slowed, the trend for all of them is still downward.

Texas oil booms and busts?

If you know anything about Texas there’s a good chance it has something to do with oil. The state is known for oil wells and you’ll see them throughout most of the state when you travel there. However, with a quick look at where the oil and natural gas is and has been in the state, you’ll also notice that the majority of the counties that have lost the highest percentage of their population are just outside the major oil fields. The loss of people had less to do with the business cycle of oil than it did with agriculture—that, of course, being the reason many of this country’s rural towns were founded in the first place.

Areas surrounded by oil or natural gas mining, like Odessa and Midland, have grown by over 20 percent in the last decade, after their populations stayed flat or declined for much of the 1980s and ’90s. Now both towns boast populations of over 100,000. Other small counties around the state in the middle of shale and oil basins are seeing slight upticks in their populations as well.

A couple of bad years is nothing that makes you feel compelled to move hundreds of miles away when your family has lived in the area for generations. In this part of the state a farmer working on the same family land for decades looks back to ancestors who made it through the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression—in the same decade—and can’t help but feel they just need to persevere too. Coincidently, or perhaps not coincidentally, the rate of suicide among farmers has been increasing the last few years.

Living in a town where your ancestors have streets and parks named after them makes leaving a difficult choice. People lament when a local store closes, or a family leaves, but with no natural or man-made disaster, it’s hard to think of these diminishments as part of a trend that has been going on for decades. Folks just sit back and recall the days when the local high school had 300 kids compared to 125 today. It’s a long but inexorable decline.

Across much of “The Big Empty” are towns like Mozelle, Clairemont, Swenson, and Gouldbusk, that almost resemble the fields that used to be the town of Tuxedo. Maybe a single last standing building separates the two, till it is gone and there’s nothing but open land, a farm, and a name place on a map. Possibly a historical marker.

An oft-heard query from those who live outside rural areas is “why don’t they just move?” Maybe as mentioned above, there’s a stubbornness or pride for some. In Texas maybe even more so than other places. However, the often-used phrase “hindsight is 20/20” never also took into account how far into the physical distance one could see with it. Economic booms in distant cities like Austin, Dallas, San Antonio, or even Odessa are hard to truly grasp until you’ve lived there in person, even if they’ve been booming for decades. Your town doesn’t feel like it’s the Walking Dead, until it does.

The Stamfords of Texas

Throughout this part of Texas, you’ll find towns like Anson, Brady, Mason, Stamford, and Coleman: towns of a few thousand people with business districts that are part ghost town, part revitalization effort, peppered with vacant and active businesses. Many are manned by the primary owner, and many have monthly rents that resemble prices closer to the per-foot costs of their big-city counterparts.

Most of these towns benefit from being the county seat and have taken on those that have left the smaller towns but wished to stay in the area. A sort of last refuge before retirement and death, or a move to a more urban area. Some towns have managed to keep things stable, like Brady and Mason, while others like Stamford and Coleman find themselves continuing to shrink, much like the smaller towns around them.

More than a few of these small towns are likely hoping to be the next Fredericksburg, a town of 11,000 that is similar in vein to Park City, Utah, with its art galleries, wineries, and historic buildings, but on the Texas prairie instead of in the mountains. With one tourism-heavy town in that part of the state already, other community leaders may want to start thinking of different ways to make something similar happen. Though the odds are there will be more towns who fall than make that leap.

One of those new ways of thinking might be coming from the newly elected mayor of Stamford, James Decker, a farmer and lawyer, who grew up in Stamford, before moving away for college. After graduating from Texas A&M, then law school, he returned to Stamford with his wife, to practice law and start a family. At 34 he is definitely one of the younger politicians in his part of the state. He also makes no attempts to hide the fact that Stamford has its share of problems.

Hiding the problems in Stamford wouldn’t be easy to do either. Driving around it’s not hard to notice, parts of Stamford, on a much smaller scale of course, are eerily reminiscent of Gary, Indiana or Detroit. Decker readily admits they have more than their fair share of abandoned properties: “We’ve demolished about 250 abandoned or blighted buildings in the city, but we estimate we have about another 500 to go.”

Despite a decline in population stretching back to the 1950s, Decker is ever the optimist about the future of the town. “I see a lot of those suburbs trying to create culture and environment. They’ve seen the niche. But they’re trying to create culture and environment of what’s been present in these rural communities since Stamford was founded.” He references how some planned suburban communities are building town squares in an effort to replicate small-town life and attract young families; basically, the things Stamford and other towns have had since the first plots were sold. “We need to embrace that and realize what people are looking for is out there, but we need to give them a reason to want to live and do it here.”

One of the things Decker isn’t looking to repeat is the old “keep doing what you’ve always done” attitude because he knows that’s just going to get more of the same. He notes that when small towns based around textiles, for example, loses half of their jobs in a short time frame that gets people’s attention in a hurry. But the loss of agriculture jobs never had that “big boom moment” and his town and others are racing against a clock that has been counting down for decades now.

Mayor Decker is hoping to make Stamford a case study in how to revitalize a rural community, in spite of a trend in rural ag communities that has been going in the opposite direction. While the future is uncertain for Stamford, he is sure about one thing: the next 30 years will be the difference between “being prosperous or being a shell of its former self”—and, he adds, not just for Stamford, but most of rural America.

Vincent David Johnson is a Chicago-based photojournalist, filmmaker, and the person behind the Lost Americana documentary project. When he’s not working on Michigan Avenue, chances are you can find him in rural America checking out a town you’re not going to see on a travel show. Follow his work at @LostAmericana.