In a Time of Trouble, Twelve Pillars of Wisdom

A recent book chronicles the life of a Catholic priest behind the Alcoholics Anonymous movement.

Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.’s Spiritual Sponsor by Dawn Eden Goldstein (2022, Orbis Books), 408 pages.

Two significant trends in America, one demoralizing and one remoralizing, are about to collide.

The demoralizing trend is the prevalence of addiction. In addition to the familiar demons of alcohol, tobacco, and gambling, newer demons, such as easily-mass-produced opioids and the dark seductions of the internet, pose dire threats.

The remoralizing trend is the revival of faith-based understanding of cultural and social problems and their remedies. We see, for instance, a surge in interest in homeschooling and school choice; the religious element in both is not far below the surface. Moreover, there is a renewed appreciation for Catholic social thought, starting with the recollection of Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum and stretching all the way to talk of post-liberal integralism.

We don’t yet know which moralizing will prove stronger, although there is plenty of evidence that America is turning away from the anything-goes attitude that has led to so much chaos, criminality, and tragedy.

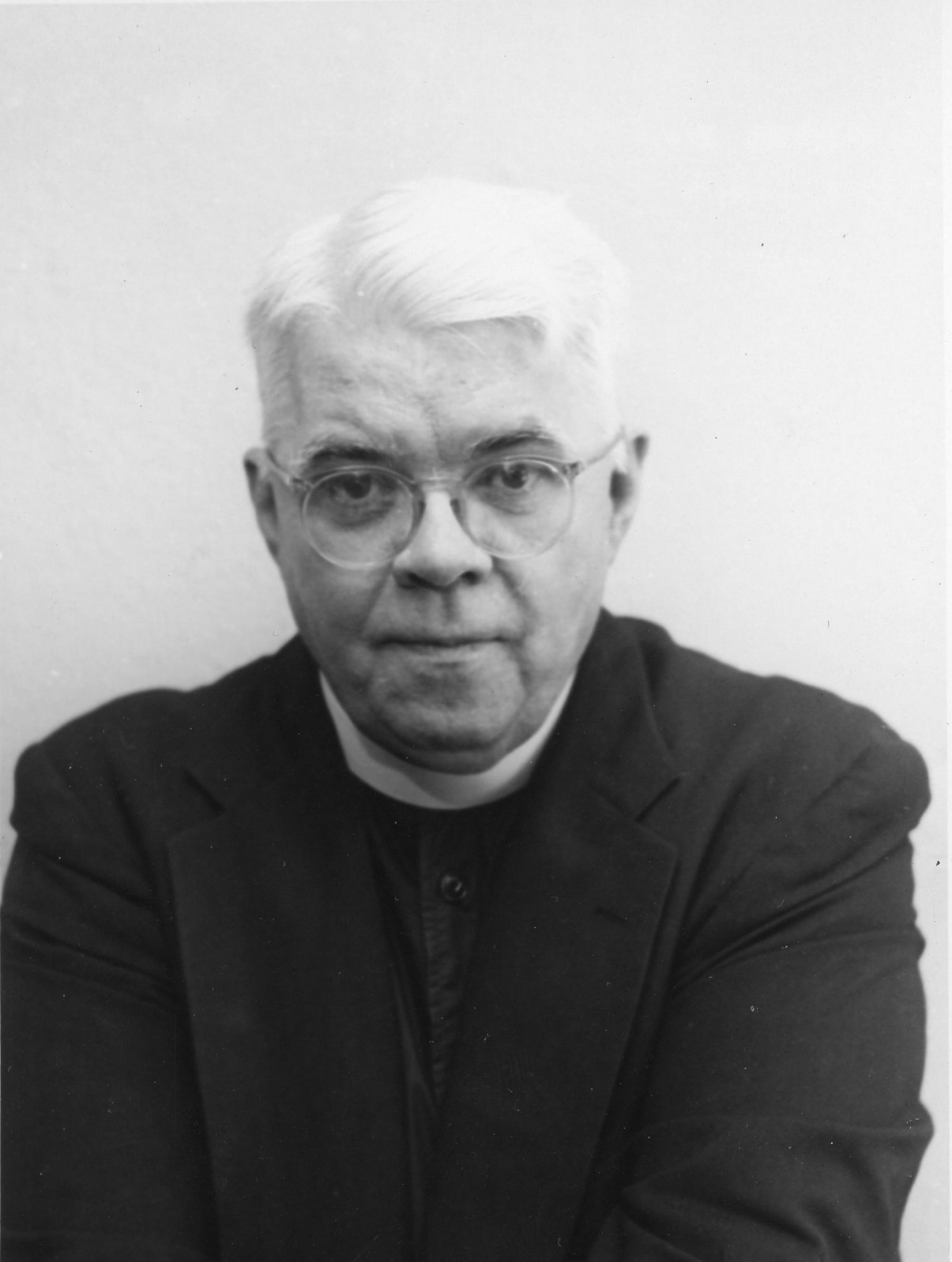

In this moment of reckoning, Dawn Eden Goldstein’s book, Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.’s Spiritual Sponsor, is propitious, as it not only recalls a neglected historical figure but also points to a tested solution. The “Bill W.” in the title is Bill Wilson (1895-1971), the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A), and “Father Ed” is the Jesuit priest Edward Dowling (1898-1960). When Dowling died, Wilson, his friend and mentee for two decades, wrote, “Ed was the greatest human soul that I’m sure I shall ever know.”

Of the two, Wilson is the better known. Having founded A.A. in Akron in 1935, Wilson spearheaded a self-help movement that flourishes, quietly, to this day. At one level, A.A. is therapy, open to all, no questions asked; indeed, the style of abbreviated last names (Bill W.) is in keeping with the nominal anonymity of its membership. And yet at a deeper level, A.A. is a waystation to faith. A.A.’s website describes itself as a “fellowship,” adhering to “spiritual principles.” And the Twelve Steps—the heart of A.A.’s path to rehabilitation and redemption—make seven mentions of “God” or “Him.”

Dowling, a lifelong resident of St. Louis, first encountered the Big Book—the Bible of A.A.—in 1939, whereupon a fellow priest, who had himself struggled with alcoholism, pointed out the similarity between the Twelve Steps and the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the 16th-century founder of the Jesuit order. The Exercises, a sequence of prayers and meditations, were of course familiar to all Jesuits. Indeed, as a mere novice in 1925, Dowling had expressed his wish to make a deeper study of the Exercises, “from philosophical, theological, sociological, educational angles.” As the young Dowling wrote to his sister, “the Exercises put humility as among the highest moral achievements—so fertile a soil for Love.”

Indeed, a decade before A.A., Dowling saw the Exercises “as providing a set of principles that could be practiced in every area of life.” Displaying the energy that has long typified the Society of Jesus, he looked forward to “popularizing their principles in these various fields.”

In chronicling how the Protestant Wilson and the Catholic Dowling came to work together in that pre-Vatican II era, Goldstein turns a keen eye on the nuances of mid-century America, when ecumenicalism was often suspect. As she explains, Protestant temperance literature “typically bore down upon alcoholics with warnings about the sinfulness of their behavior.” By contrast, the Big Book was more implicitly “Catholic,” being an “intense call to self-examination, conversion, and trustful surrender to God’s transformative grace.”

Goldstein herself is a study in transformation. Born Jewish, and once a pop-music writer who saw rock-and-roll as a kind of religion, she worked for tabloid newspapers in New York City before converting to Catholicism. In 2016, she became the first woman to earn a doctorate in sacred theology from the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein, Illinois; she is thus well grounded to describe how the sacred can coexist with—and operate within—the secular.

Thanks to A.A. and the Big Book, Dowling had a new lens through which to see personal torments. He himself was never an alcoholic, although he did wrestle with depression, and he applied Twelve-Step principles to what he called his “nicotinic addiction.” Yet Dowling always felt the call to look outward. As Goldstein puts it, “After he encountered A.A., he devoted much of his pastoral work to adapting the Twelve Steps to help people with any type of problem.” These problems included marriage counseling, poverty, and discrimination. (Goldstein steps lightly on Dowling’s application of the Twelve Steps to homosexuality.)

To read Father Ed is to be carried back to a different era, when Catholic influence was at a peak, when Hollywood made church-centric films such as Boys Town, The Song of Bernadette, Going My Way, and The Bells of St. Mary’s, and when Dowling’s St. Louis was a major hub viz. another movie of that era, Meet Me in St. Louis. Figures such as Charles Lindbergh, Gerald P. Nye, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, Judy Garland, and Fulton Sheen make appearances, ably contextualized. We even meet the descendants of Dred Scott, whom Dowling befriended and aided, and Father William Bowdern, the priest who inspired William Peter Blatty’s novel-turned-movie The Exorcist.

Dowling was an activist—for a brief time with the America First movement, and for a longer time championing labor rights and civil rights. Yet for much of his life, he was slowed down, even crippled, by ankylosing spondylitis, an arthritic condition. So much of Goldstein’s biography is epistolary and intellectual; to capture the life of Dowling’s mind, she has dug deep into the archives of Maryville University Library and the Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

In her scholarly hands, Dowling comes to life as a man with a mission—and actually, many missions, practical and spiritual. For all his close association with Wilson, Goldstein writes that Dowling’s “true purpose went well beyond sobering up drunks.” In one talk to an A.A. group in Delaware, Dowling declared

In the Alcoholics Anonymous plan of life, one finds an overall plan for personal adjustment. . . . When the A.A. movement was founded, it just happened that the immediate problem with Bill, the founder, was alcoholism. It is a program no less effective for other things.

What “other things”? In a 1944 piece in The Queen’s Work, a now-defunct Jesuit publication, Dowling asserted,

If you can’t stop biting your fingernails, growling at your mother-in-law, or are obsessed with any other deteriorating habit, just substitute your vice for alcohol in the following twelve steps and see if you have the courage even to start the program. It is very practical for men and women who are drinking too much loneliness, anxiety, and discouragement these days.

Indeed, the cleric had thought through many angles: “In moving their therapy from the expensive clinical couch to the low-cost coffee bar, from the inexperienced professional to the amateur expert, A.A. has democratized sanity.”

Yet for all his secular-sounding pitchmanship, Dowling never lost sight of his ultimate mission, which was connecting A.A. to Christianity:

Some 1900 years ago, a man named Peter sat down and wrote a letter to the members of some new groups that had formed. And this is one [thing] he said: “Be sober and watch, because your adversary, the Devil, as a roaring lion, goeth about, seeking whom he may devour. Whom resist ye, strong in faith.” Strong in faith. God keep you so.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

The passage doing duty here is 1 Peter 5:8–9.

Six decades after Dowling’s death, we see that roaring lions of degradation are still devouring, perhaps hungrier than ever. That’s the bad news. The good news is that Americans are realizing that various social experiments—including decriminalized, even legalized, even assisted, drug use—have turned out catastrophically. And while there’s no consensus as to exactly what to do instead, there is a realization that we have to make a change.

So Goldstein has picked a good time to remind us of the Twelve Steps. For instance, there is Step Four, in which we make “a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.” That is a good one. And there are eleven more, all just as good.