In a Desert City, Frank Lloyd Wright and Traditional Architecture at Play

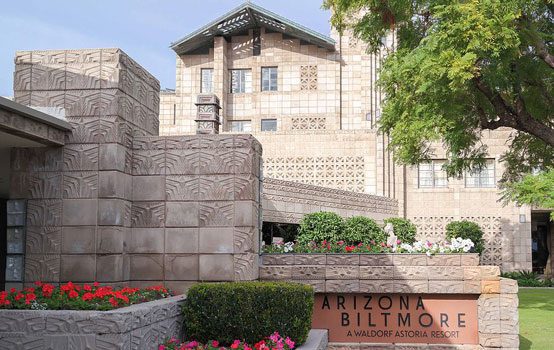

PHOENIX, Ariz.—For a building completed in 1929, the Arizona Biltmore resort hardly reads as “traditional architecture.” The prominent construction medium of gray sandstone blocks expresses a modern edginess. The front entrance is oddly asymmetric, with a geometric tower over the front door flanked on one side by a gable and on the other by an enclosed arcade. Traditional elements such as columns and vaults are certainly present but with unexpected configurations and details, and the silhouette is decidedly avant-garde.

But the more I explored the hotel, the more I became convinced that despite the aggressively stylized detailing, the Phoenix landmark is filled with traditional design elements—largely because of the use of human-scale doors and hallways and the entire layout’s dependence on terminating views. The Biltmore is an example of the vibrancy and potential within traditional design elements, demonstrating that the boundaries of traditional architecture are far broader than the Neoclassical, Federalist, or other “types” we often associate with the term.

Traditional architecture attempts to make sense of a space using shapes and materials that invoke symbols and forms that are already embedded with meaning for the people who will use the space. It differs from truly modern architecture in appealing to a shared sense of meaning—it believes in culture, in other words, and knows that limits in its ability to communicate are directly shaped by the limits of the culture’s collective imagination.

Modern architecture, on the other hand, tries for various reasons to break with symbols that already have cultural meaning. These reasons could include an overt rejection of tradition; a desire to express the architect’s personal philosophy in code; or an attempt to elicit a particular emotional response (usually an unpleasant one) disconnected from actual rational content. For example, modern architects may use oppressive spaces and shapes to communicate, without words, the philosophical view that every individual is completely cut off from every other, and that no experience can be truly shared. This is different from the emotional response one has in a cathedral; there, the architectural elements that lead to emotional responses are directly connected to the building’s purpose—glorifying God through a space—rather than existing solely to elicit a response.

***

Phoenix’s Arizona Biltmore Hotel and Resort was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and his former student Albert Chase McArthur in 1928. McArthur served as primary architect, but the resort demonstrates Wright’s signature quirkiness in spades. Though Wright, used to having complete control over his architectural projects, ended up in conflict with McArthur over the design of the resort, it is not hard to see Wright’s influence on the final product. For example, the primary building medium is fabricated sandstone blocks made from sand found on the building site (a Wright standby), each bearing an imprint of an Art-Deco design based on the palm trees that fringe the Phoenix skyline.

The Biltmore, like Wright’s other buildings, does not bring “classical” architecture to mind. It consists almost entirely of elaborately etched concrete blocks, stacked in walls of unexpected angles that give the whole place a maze-like feeling. In keeping with Wright’s commitment to what he called “organic architecture,” the buildings incorporate colors, shapes, and designs from various Native American traditions. The ceilings are almost all lower than expected, with the exception of the main hotel, which has a high-ceilinged but pleasantly narrow lobby, creating a space that has more in common with a medieval nave than a shopping mall.

The hotel was built in 1928, long before air conditioning made it possible to live in Phoenix year-round with any degree of comfort. Like Wright did with his nearby Arizona winter residence at Taliesin West, the Biltmore closed up in April every year and did not reopen until October. Awareness of this geographic reality is evident throughout the design: The low ceilings and thick concrete brick walls make the interior spaces feel cave-like, cool and moist from the interior water features. A design that would feel absolutely stifling in Michigan or Wisconsin—gray walls, small interiors and windows—is a blessed relief in Arizona, no matter what time of year it is.

Where I found the design of the Biltmore to most strongly invoke traditional architecture is in its dynamic between mass and negative space. In the resort, there are many long, surprisingly narrow halls (both indoor and outdoor) with unexpected angles that give a sense of being in a much larger complex than the Biltmore actually is. As I walked around the resort, the patterns reminded me of places with a very different aesthetic, such as small towns in Northern France: the curved or angled streets, the endlessly terminating views, the difficulty of understanding just how big a place is—and eventually, not caring how big it is and simply enjoying it. Contrast this with the experience of looking down a 30-mile, six-lane artery that runs through the middle of town, or an unadorned hallway that runs directly down the middle of a office-park building and ends at right angles to a wall of the same color as itself; these views make the viewer feel lost or subsumed in a massive, impersonal project, rather than underscoring his role as an active, intelligent, and imaginative participant in the landscape.

The sense of space that results from the elements that make up terminating views—slightly narrow streets, doorways, and buildings built on slight angles or curves—is simultaneously cozy and full of possibilities. There is something inescapably traditional about a graciously terminating view—not, to clarify, the view terminating at some inexplicable angle in the slab wall of a Brutalist heap. When well designed, a line of sight is not snapped off at the end but eases its way to the termination along a curve in the street or a series of stacked obtuse angles.

Such a space acknowledges that our experience must be moderated by reasonable limitations (the termination of the view), but it leads up to those limits by way of curves or welcoming, open angles that cause us to want to peek our heads around the corner and explore in another direction, where ideally we’ll find another gracious terminating view. The limits imposed by these kinds of spaces are realistic—much more realistic than the endless corridors of modern office complexes—but charitable. They indicate that much more lies within our limits that we perhaps perceive right away, and invite us to explore within them.

I was surprised to find these traditional architectural elements at play within the Biltmore resort. The concrete-block walls ease visitors gently around curves to unveil an unexpected new vista—a hidden, classically geometric garden, a swimming pool, a café veiled by oleander.

The point made by the space is that tradition can exist side-by-side with innovation, using technologically advanced materials in unexpected geography like the Arizona desert. Creativity in architecture doesn’t have to mean abandoning traditional elements and proportions, or the traditional narrative about the human participant in the space. The presence of the Biltmore in the midst of a city like Phoenix should be a reminder that beautiful, well-designed places are not restricted to a certain time or place, and a challenge to architects to find fresh ways to incorporate traditional elements into their spaces.

Jane Scharl writes from Phoenix, Arizona.