How a Denver Coffee Shop Exploded the Gentrification Debate

The “gentrification” phenomenon unfolding in many American cities shows no signs of abating, as “gentrifiers” move into deteriorated urban neighborhoods, renovate homes, start new businesses, and pave the way for other people of higher incomes to follow. The result is usually the transformation of those neighborhoods. Of course such transformations often entail significant changes in the socioeconomic mix of the area and often in its ethnic and racial composition as well. That can generate controversy and civic anger.

That’s what happened late last year in Denver’s historic Five Points neighborhood, where a poorly worded sign set off civic agitations and attracted unwanted national attention. Around the Thanksgiving holiday, “ink! Coffee,” a Denver-based coffee chain, put up a sign outside its shop that contained a bit of a boast. It read: “Happily Gentrifying the Neighborhood Since 2014.”

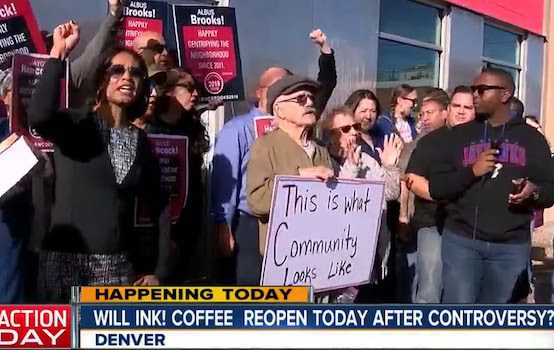

Bad move. The sign didn’t go over so well with some residents, many of whom congregated outside the little coffee shop in an angry mood. Hundreds showed up during a subsequent weekend to protest against the gentrification of their neighborhood, which they said had pushed out longtime minority residents. The shop building was sprayed with graffiti; at least one window was broken; the offending sign was carted off. The protesters demanded that the shop be shut down. Some wanted it replaced with a community center dedicated to helping residents with housing and other issues stemming from rising living costs in their neighborhood.

The shop was forced to close for more than a week. After it reopened I stopped by for a weekend visit. The broken glass on its front window had not been replaced. Although there were no protesters, the store was shuttered that day. A sign on its front door said it closes on weekends during winter, which seemed odd since weekends should be a busy time for a coffee shop. Indeed, the competing vendor across the street was open and packed with customers. It seemed that ink! Coffee was still struggling to recover its lost business.

♦♦♦

And the controversy didn’t recede quickly. A city councilman who represents the Five Points area suggested that ink! Coffee should have each staff member go through “cultural competency training,” presumably to ensure that staffers don’t harbor bad racial attitudes. The councilman, Albus Brooks, urged the coffee shop company to pressure employees into making charitable contributions in the neighborhood to demonstrate their civic good faith in the wake of the sign fiasco.

That led Vincent Carroll, a prominent retired newspaperman, to opine in The Denver Post: “In other words, an employee who has done nothing more offensive than greet customers with a smile while cheerfully inquiring what beverage they would like to order should be treated as a potentially bigoted ignoramus requiring an attitude adjustment.”

Carroll elicited a torrent of angry reaction when he called the protest against ink! Coffee “an embarrassment to Denver.” Anyone who expected the neighborhood of his youth to remain unchanged, he wrote, was “shockingly nave regarding the relentless power of the social and market forces that trigger such naïve makeovers.” He added there may be “one sure-fire cure” for gentrification: “urban decay and recession.”

That led one Post letter-writer to characterize Carroll’s op-ed piece as “embarrassing in its condescension.” Another wondered, “What’s Vincent Carroll smoking?”

Denver is of course not alone in being buffeted by intense feelings on the gentrification issue. In his Post article, Carroll cited press reports noting that the issue had roiled last year’s mayoral race in Atlanta, which in 50 years has gone from being majority white to majority black—and now seems on the threshold of becoming majority white once again.

And in Illinois earlier this year, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Chris Kennedy (yes, of those Kennedys) attacked Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel for what he called a “strategic gentrification plan” aimed at forcing African Americans and other minorities out of Chicago to make the city “whiter” and wealthier. The allegation backfired, as critics quickly alleged Kennedy was simply trying to exploit Emanuel’s poor standing with blacks in his city as a way of cementing his own support from African Americans in his gubernatorial run. The Chicago Tribune expressed a hope in an editorial that the governor’s race wouldn’t “get any uglier than it did this week” and suggested Kennedy had “hallucinated aloud” in pressing his allegation against the mayor.

Still, though Kennedy’s allegation lacked credibility and seemed politically motivated, it demonstrated just how emotional the gentrification matter can be, irrespective of the merits surrounding any particular controversy stemming from the issue.

♦♦♦

As for the Denver controversy, the question that emerges is why the word “gentrification” got so many residents of Five Points so riled up. Here we see the role of local loyalties and sentiments. It has everything to do with the history of Five Points, an area also known as the “Harlem of the West.” It is one of Denver’s oldest and most diverse neighborhoods. Named “Five Points” in 1881 for the five-way intersection of 26th Street, 27th Avenue, Washington Street, and Welton Streets, it historically has been a predominately African-American neighborhood. Back when it got its name, it was known for its jazz music scene and vibrant commerce. From the 1950s to 1990s, however, the community deteriorated due in part to drugs and crime. Properties were abandoned, and many businesses shut down. Many residents who were able to move did so. And many who were left behind languished in poverty.

The City of Denver has tried to revitalize Five Points many times through the years. But those efforts have fallen short due to Denver’s frequent economic boom-and-bust cycles. Thus did residents of Five Points become accustomed to empty promises. Around 2005, however, Denver’s economy finally took off with the energy boom, a growing tech sector, and an explosion in the craft beer industry. Buoyed by Colorado’s $2.7 billion craft beer industry (first in the nation), Denver has become the craft beer capital of the world. Meanwhile, U.S. News & World Report ranks Denver number two on its “Best Places to Live” list, both reflecting and spurring an ongoing influx of new citizens to the city and its environs.

Denver’s booming economy and vaunted quality-of-life index have particularly attracted, it seems, people of the distinctive Millennial generation, Americans born in 1984 or later. These young migrants—with strong lifestyle preferences—prefer to live in cities, particularly diverse neighborhoods within walking distance of nightlife and entertainment. Some of them streamed into Five Points. Businesses catering to these young and affluent newcomers quickly followed. Today’s Five Points is also known as “RiNo,” or River North Art District, an ultra-trendy zip code that features microbrewery bars, new age restaurants, contemporary art galleries, and hip concert venues.

Mod Livin’ Rino, a furniture/interior design shop, is one such new Five Points establishment. It sells finely crafted mid-century classic furniture with a modern flair. I noticed a lovely chair selling for $700 and a chest for $3,000. An interior designer who works at the store told me that the store owner is a Denver businesswoman who owns another furniture store on the more established East Colfax Avenue. She decided to open her second store in Five Points to get closer to a young, hip clientele.

But with the growth of Five Points came growing pains. The booming economy and expanding population have pushed up demand for housing. Denver is one of the hottest real estate markets in the nation, and Five Points is the hottest area in Denver. According to Zillow, the median list price per square foot in Five Points is $426, considerably higher than the Denver average of $343. The median price of homes currently listed in Five Points is $569,900.

Many long-time residents have left the neighborhood, including minorities (many of whom can no longer afford housing in the area). Though the neighborhood was once dominated demographically by African-Americans, today about 79 percent of residents are white. Further, some mom-and-pop businesses and independent artists, long a significant part of the social and economic scene, are leaving too. A notable closure was Tom’s Home Cooking, a beloved Southern soul-food eatery that had been an anchor in the community for 16 years.

During my recent visit I talked to Price Davis, owner of a neighborhood art studio. After some 23 years in Five Points, he now is in the process of closing his art studio. Davis explained that his property taxes have doubled just in two years, to $18,000 annually from $9,000. His insurance costs also skyrocketed. The cost of doing business makes businesses like his untenable, said Davis. Among his artist friends in Five Points, only five remain, and they all expect to depart sooner or later. Davis believes that the City of Denver prefers to bring in big corporations to Five Points rather than make an effort to keep independent businesses like his. Not far from his studio, a Shake Shack sign is hanging on a construction site, as if to bolster his point.

♦♦♦

The diversity of population and art has for years contributed to the attractiveness of Five Points. Though gentrification has brought economic growth and safer streets, it has also frayed the social fabric and eroded the community’s historic charm.

Besides, many argue that the area’s new economic growth hasn’t benefited everyone equally. About 40 percent of remaining minority residents still live below the poverty line, most of them in the area’s central and southeastern sectors. These are places that still have plenty of run-down properties and high crime rates. Residents there are also stuck with one of the worst public schools in Denver, Manual High School. In contrast, Five Points newcomers generally can afford $2,000 monthly rents and can send their children to high-performing schools outside Five Points.

Given all this, it isn’t difficult to see why some of the area’s long-time residents reacted angrily to ink! Coffee’s poorly worded sign. (Another one, at a different location, was even more insensitive: “Nothing says gentrification like being able to order a cortado.”) But of course vandalizing a coffee shop is a criminal act. Beyond that, it’s counterproductive, likely to scare new businesses away. And shutting down ink! Coffee isn’t likely to help the neighborhood or anyone who lives there. Low income residents can’t afford to reject economic development. Without an influx of new business, there can be no expanded employment opportunities or economic upward mobility. Five Points’ long years of economic languishment, prior to gentrification, certainly illustrate the point.

The City of Denver has tried to address the housing affordability issue with the typical progressive tools. Through zoning policies it sought to mandate that developers set aside a number of new development units as “restricted units,” to be sold or rented at government-determined affordable rates. But the unintended consequences weren’t difficult to predict. With prospects for profitability reduced or eliminated, developers abandoned drawing-board projects. With incentives to create new housing reduced, there was less housing. With less housing, real estate prices rose.

Such governmental policies distorted the market and ended up worsening the very problems they were intended to fix. Ruinous zoning and tax policies aren’t the answer. Letting the free market do its job is the only way the low-income residents of Five Points will have a fighting chance for a better life. As Vincent Carroll puts it, it’s no wonder that every so-called fix for displacement—housing subsidies, property tax assistance, construction mandates—“sounds positively puny compared to the surge of folks willing to pay what is necessary to move into neighborhoods they like.” Besides, he adds, critics should understand that “businesses that flock to revitalizing neighborhoods lift the tax base on which crucial government services depend.”

Helen Raleigh is a senior contributor to The Federalist and the author of Confucius Never Said.