E.R. Dodds and Our Age of Anxiety

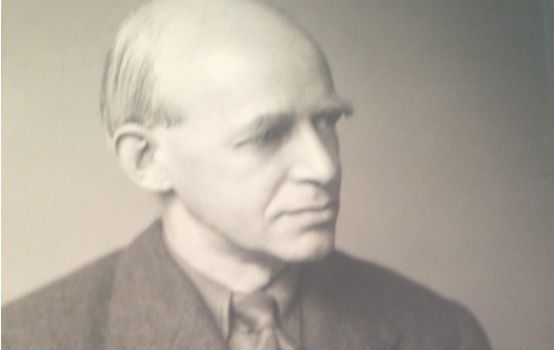

Almost 70 years ago, the celebrated Oxford classicist Eric Robertson (E.R.) Dodds—friend of T.S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley, mentor to W.H. Auden—challenged a set assumptions about classical rationality. Influenced by Jungian psychology and studies of the unconscious, Dodds surveyed “elements in human nature which govern without our knowledge.” In doing so, he changed the way historians think about Greek and Roman antiquity.

In The Greeks and the Irrational, Dodds explored the ancient flight from reason and humanism after the age of Plato and Aristotle, a long intellectual decline regressing to magic and astrology. Self-awareness and worldly error, Dodds suggested, produced guilt and self-doubt. Hellenic and modern civilization had created “progressive societies with remarkable achievements in philosophy and science” but seemed unable to sustain “the heavy burden of individual choice which an open society lays upon its members.”

Dodds compared this “fear of freedom” to modern uncertainty, repeating author André Malraux’s concern that “Western civilization has begun to doubt its own credentials.” His conclusions offer instructive parallels to recent thought from Andrew Sullivan, John Gray, and other leading social critics about contemporary identity politics and irrationalism.

Dodds’ 1965 book Pagans and Christians in an Age of Anxiety described religious conflict in Roman society during the rise of Christianity. Bread and circuses, bad emperors, and barbarian invasions might have doomed ancient Rome, but Christian do-gooders corroded Roman society from within, as Edward Gibbon observed. And Christians, once they got into power, shut down everyone else.

In 380, Theodosius I declared Christianity the official religion of the Empire, proscribing all other religions. Temples were closed, property confiscated, pagan holidays prohibited, and Olympic games ended. Freedom of religion vanished. Yet Christianity’s inheritance of classical philosophy led to intense intramural quarrels about God and theology rather than doctrinal unity.

The corrosion of pagan standing had begun many years earlier. Seeking martyrdom in 165, the exhibitionistic Peregrinus burned himself to death in a spectacular suicide at the Olympic festivals before an admiring crowd, becoming a Christian hero. Was he crazy or prophetic? Last month, LGBT-green activist attorney David Buckel similarly set himself on fire in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, warning of ecological catastrophe and human selfishness.

The early Christians did not doubt their credentials. Many of them—women, slaves, and miserable freemen—had little to lose from living outside the law. These rag-tag enthusiasts at first seemed treasonous, unpatriotic, or maybe even crazy. Christian failure to acknowledge the emperor’s birthday with a few grains of incense, said Dodds, was “deliberate and insolent expression of disloyalty, rather like refusing to stand up when the national anthem is played.”

This obnoxious self-confidence made Christians many enemies among ordinary Romans. “Like all creeds which claim the total allegiance of the individual—like communism, for example, in our own day—early Christianity was a powerful divisive force,” Dodds said, using italics to make his point.

To educated pagans, blind faith rendered Christianity contemptible. But what had been no more than an administrative nuisance or psychological curiosity in the early Empire became an actual menace to its stability and security: a state within the state, a secret society that disrupted social cohesion. The split between Christianity and idolators involved ruined friendships, traumatic family breakups, and disinheritances.

Caught in this transition, the eminent poet and statesman Ausonius (c. 310-395) provides an excellent example of 4th-century ambivalence. He lived as a professed Christian in the middle of spiritual disputes, outwardly observant, but only that. A public man, he thought Rome was forever and indestructible. He was crushed when his protégé and close friend Paulinus renounced high Roman imperial office to become a cleric. As did other bluebloods of the era, including the saint-to-be Augustine of Hippo, Paulinus chose a clerical career in lieu of state service.

Why did the Christians win the Roman culture wars? First, the anything-goes ecumenism of late antiquity led to “too many cults, too many mysteries, too many philosophies of life to choose from: you could pile one religious insurance on another yet not feel safe,” Dodds explained. “Christianity made a clean sweep.” The Church cared for widows and orphans, the old, unemployed, and disabled. Most important, the Church created a community that gave self-respect and meaning to lives, provided human warmth, and offered hope.

Since Dodds wrote, the Western world’s educated and powerful have for the most part abandoned Christianity. Multimedia blur fiction and fact, making fantasies appear real and true. In such a world, what rubrics will provide a moral anchor and semblance of community? What voices will give lives meaning and direction?

Washington-based journalist Andrew Sullivan has likened today’s campus activists to a religious sect, one that finds redemption through confession of white guilt and privilege, conversion, adoption of esoteric language, and adherence to a strict moral system. “Liberalism and empiricism have parted company,” warns political philosopher John Gray, an academic leftist and no friend of religion, in the Times Literary Supplement.

Crazy or prophetic? A rising quasi-religion propagates articles of holy faith through academic and corporate workshops, training sessions, and safe-zone certifications. In deconstructing canonical works, defaming ancient heroes, denouncing thought crimes, destroying icons and symbols, and closing down opposing viewpoints as hateful, it displays humorless fanaticism. The election of bad-emperor Donald J. Trump only deepens its zeal.

But its path to individual and worldly redemption violates human experience. Gray in particular questions its capacity to create a new global order that has been “nowhere encountered in history, which does not need to define itself through family or community, nationality or any religion.” Unlike Christianity, this quasi-religion offers no promise of eternal life. It gives off little warmth or kindness.

Likewise, the emerging intersectional priesthood has no intention of ceding secular power or accommodating adversaries. As an elect mindful of the responsibility to crush lies, convinced of its superior moral vision, it demands greater temporal power to redeem and punish recalcitrants.

As Dodds showed, belief systems that seem absurd to non-believers can and do create state-enforced thought monopolies. Once institutionalized, they can remain in power for long periods of time. Those who refuse to embrace sacred mandates and hierarchies are deplorable. They are mad, stupid, or evil, not merely stubborn or freethinking. Heresy contaminates. Nonconformists deserve legal reprisals, stigma, and ruin. To expunge the demonic threat, autos da fé, psychiatric hospitals, labor camps, and confiscations—many possible tools—are available to enforce divinely inspired righteousness.

Ironically, the radical critique of Western society depends on freedoms whose protection its adherents seek to curtail. What seems to give them energy is destruction, a faith that is unlikely to advance humanity or create what is glibly called “a better world.”

Dodds hoped that the West could sustain a reasoned, open civilization, perhaps through tools of psychotherapy. But decades later, psychotropic medicine and an electronic wonderland are what science and technology have rendered. As a consequence, today’s retreat from reason calls to mind Dodds’ friend Aldous Huxley and Brave New World as much as his own studies of Freud and Jung.

Gilbert T. Sewall is co-author of After Hiroshima: The United States Since 1945 and editor of The Eighties: A Reader.