The Limits of Father Neuhaus’s Vision

I have been waiting to see what former First Things editor Damon Linker had to say about the new biography of Richard John Neuhaus. Damon — who is a friend — famously fell out with Neuhaus, and wrote a scathing book denouncing Neuhaus and his closest collaborators (Weigel, Novak) as “theocons” who sought to take over America. The attack made Damon permanent enemies within Neuhaus’s circles, in part because it seemed to them a kind of intellectual patricide. At the time, I thought Damon’s argument was extremely overdone, not because I was a pro-Neuhaus partisan (though I was a fellow traveler), but because it seemed to me to vastly exaggerate the power the theocons had.

It would be interesting to re-read Damon’s book now, almost a decade later, and see how it holds up. Rather than Neuhaus’s religion having corrupted American politics, it seems that exactly the opposite happened: American politics tainted Neuhaus’s religious vision. Damon begins his favorable review of the Neuhaus biography with an anecdote that symbolizes much:

I knocked on Richard John Neuhaus’ office door in late 2002 to tell him I wanted to write an essay for the next issue of First Things making a conservative case against invading Iraq. Neuhaus was the editor-in-chief of the conservative magazine, and I was his associate editor. I ran the book review section at the back of the book, helped editor James Nuechterlein line-edit the journal, and sometimes wrote essays and columns for its pages.

Neuhaus responded to my proposal in a tone of grave seriousness. “Oh Damon, that’s really not a good idea. You don’t want to get a reputation for being unreliable.”

Damon told me that story years ago, and the story tracks with a similar tale a First Things insider passed along some time back regarding Neuhaus, the magazine, and the war (which, cards on the table, I supported, in part because I agreed with the magazine’s stance; I have since come to believe that the Pope was right, and Neuhaus, Weigel, and all of us American theocons who supported the war, were wrong). The picture is one in which being seen as loyal to the team was more important than being right.

I don’t believe that Neuhaus was cynical; to the contrary, I think he was a true believer. And yet, when I read that Linker anecdote, I recall one of several angry telephone conversations Neuhaus and I had in the spring of 2002, when I was writing at National Review, and strongly — sometimes, I must admit, with an intemperance that I now find regrettable — criticizing the Roman Catholic bishops for their cowardice and cover-ups in the child sex abuse scandal. In one of those phone calls, Neuhaus excoriated me for letting down the side. He told me that if I persisted in criticizing the bishops, I was giving aid and comfort to the enemies of the Church, who would use politics to restrict the Church’s hard-won freedom to act.

I think he had a point. But it was telling that he was more interested in protecting the Church’s power and reputation in the public square than in exposing and correcting a great evil within the institutional church. In light of that cause, I was, well, unreliable. That general instinct, I believe, led Fr. Neuhaus — an indisputably great man — to make some key errors of intellectual judgment. He put his hope in the wisdom and rightness of the Bush administration, and in the wisdom and rightness of his team within the Church — the latter of which led to what I consider to be at best a calamitous embarrassment: his stalwart defense of the evil Fr. Marcial Maciel, and his strong attack on Maciel’s accusers, who, in the end, turned out to have been right.

Damon, who knew Neuhaus (I did not), agrees that Neuhaus was not a cynic about his alliance with the neocons:

But Neuhaus’ reaction to my proposal was not just a function of inside-the-beltway ambitions. It was also personal, an outgrowth of some of his deepest and longest-lasting intellectual convictions. Back in the late 1960s, when he was a self-described left-wing revolutionary, Neuhaus had suggested that the North Vietnamese were “God’s instruments for bringing the American empire to its knees.” He had migrated to a polar-opposite ideological position long before the time of the Iraq War, but he remained certain that America’s actions in the world were somehow central to God’s plans.

Damon goes in to praise Randy Boyagoda’s Neuhaus biography, even though it criticizes him (Damon) pretty strongly. He says that reading it made him regret that his and Neuhaus’s relationship ended as acrimoniously as it did:

I had no business working at First Things. I was never as religious as Neuhaus, and I never shared his views about the essential role of religion in American history and public life. Those are important differences. But the most intractable one — the one that eventually turned me from a dissenting friend into a publicly declared enemy — was our deeply antithetical views of the proper relationship of politics to the life of the mind.

I have a genuine respect for politics, recognize its importance and dignity, and think that it reveals certain aspects of human nature more vividly than any other activity or pursuit. But I also believe very strongly that its loyalties and commitments, its partisanship and partiality, stand in permanent, irresolvable tension, even fundamental contradiction, with the pursuit of truth, whether through reason or revelation. When philosophical, theological, or historical ideas are blended with political passions and convictions, the result is very often a species of propaganda.

Reliability may well be a political virtue. It’s also a pretty serious intellectual vice.

Boy, is that ever true — and it’s a vice that all of us are tempted to indulge in, no matter what our political and religious convictions. Favoring solidarity to the cause and its advocates over truth-telling — especially telling the truth to our friends and allies — is a recipe for disaster.

You really need to read Damon’s essay to see what he thinks of as Neuhaus’s most valuable legacy as a thinker: not his efforts as a politically engaged theologian, but his pensées as a suffering Christian. I read the Neuhaus book Damon praises, and agree with him that it is beautiful and profound. I thought about Neuhaus’s book about his own cancer many times when my sister struggled with it.

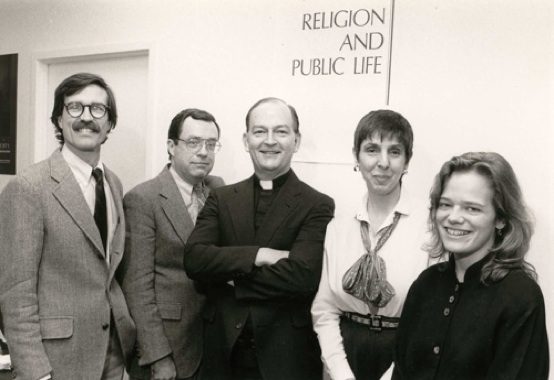

There is an enormous, Neuhaus-sized hole among the theocons today. I came to disagree with much of what he stood for, but I cherished the man as a thinker and a writer, and deeply miss his voice. We are in a post-Neuhaus age with regard to how conservative Christian thinkers consider the place of religious believers in the public square. The symposium First Things convened last autumn at its offices served as an unofficial recognition of that fact (or so it seemed to me). Read the reflections of Michael Hanby, George Weigel, and Your Working Boy, offered at that meeting.

I hope that one valuable lesson we theocons have learned from that era is that whatever role orthodox Christianity has to play in American public life, acting as chaplains to the Republican Party must be completely off the table.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.