Purgatorio, Canto XXIV

Readers, before I forget, on Sunday, BBC Radio 4 is broadcasting (online, for us Yanks) Part I (Inferno) of a three-part radio play of the Divine Comedy. John Hurt plays older Dante. It says 3pm, which I guess is GMT, meaning four hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time in the US. I’ll be in church when it broadcasts live, so I’m hoping they’ll archive it online.

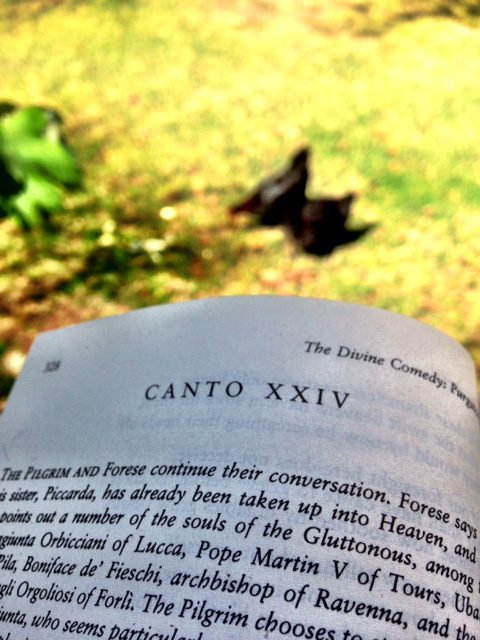

Made it back home late last night, just ahead of the bad weather here and the earthquake there. I’ve been sleeping most of the day. It’s a cool, windy, sunny afternoon here, and I’m on the side porch, reading and watching the chickens cluck and pick in the yard. There are worse ways to spend one’s afternoon.

Forese continues to show Dante around the terrace of the Gluttonous, emaciated from their fierce fasting. They are not ashamed to be identified in Dante’s eyes, despite their horrifying appearance. This reminded me of something the man who drove me from Pepperdine to LAX told me. When he heard what part of the country I was from, he, an older black man, said he had once worked in New Orleans as a waiter in a well-known restaurant.

“The head waiter was a white man who had been high up in the Klan in Louisiana,” the driver told me. “He was one of the finest men I’ve ever known. Something happened to change him. A lot of us waiters were black, and when we found out who he had been, gave him hell for it. He just took it. That’s when I knew he was for real.”

“For real?” I said.

“Yeah, that he had changed,” the driver continued. “I’ve been around drunks and addicts before, and you can always tell which ones have beaten their problem by how they act when their problem comes up. The ones who are over it are humble about it. The ones who get all defensive, those are the ones still struggling with it. That man I worked for, he died of a heart attack when he was only 53. A fine man.”

Humility.

Among the emaciated Gluttonous is Pope Martin IV, his “face more cracked and scaly than the rest.” By his fasting, he “purges eels from the Bolsena served alla vernaccia.” In his notes on these verses, Hollander says that Martin IV was known for his devotion to this delicacy, which required drowning Lake Bolsena eels in Ligurian white wine, then roasting them. Martin would also come out of church meetings and exclaim, “O Lord God, how many ills must we bear for Your holy Church! Let us have a drink!” and repair to the table for consolation. A pontiff after my own heart, that one!

One of the shades asks Dante if he is the author of a particular romantic poem. Dante answers:

“I am one who, when Love

inspires me, take note and, as he dictates

deep within me, so I set it forth.”

This is a key tercet, because it indicates how Dante is being changed by his pilgrimage. He began as a poet who praised Love as passion ungoverned by reason — a passion that, as he saw with Francesca and Paolo in Canto V of Inferno, can take hold of readers’ hearts and lead them to damnation. He has learned that God is Love and Love is God, and therefore that he, the poet, can only trust his inner voice if it is guided by the Holy Spirit — that is, conditioned by the truths of Christian revelation.

After Forese and Dante part, the pilgrim and his two companions come upon quite a sight:

Suddenly a second tree, its branches green

and weighted down with fruit,

caught my eye as we came nearer.

I saw a crowd beneath it raising up their hands

and calling — I don’t know what — up at the foliage,

like headlong, foolish children

who beg, but he from whom they beg does not reply

and, to make their longing even stronger,

holds the thing they want aloft and does not hide it.

Then they went away as if enlightened…

This, we learn, is a shoot of the Tree Of The Knowledge Of Good And Evil, from which Adam and Eve ate, in defiance of God’s command. The Gluttonous are, of course, starving, and crave the fruit of the tree. But the divine voice from within the tree apparently (for Dante can’t hear) tells them that they may not taste of it, because that would be to re-enact the deed that caused the Fall. At least that’s what Dante, Virgil, and Statius hear when they come near to it. This is a test of the depth of the Gluttons’ repentance. They obeyed the authority of God’s voice, not the commands of their cravings.

Then, a bright shining Angel appears, to show the pilgrims to the next terrace, along “the road for those who would find peace.” Dante:

His shining face had blinded me,

so that I turned and walked behind my teachers

like someone led by only what he hears.

That’s the Hollander translation, but I think the final line in Musa’s version makes this a little clearer: “letting the words just heard direct my feet.” See what happened there? Dante was so struck by awe at the divine — symbolized by his temporary blindness in the presence of the Angel — that he obeys right authority without thinking about it. He does exactly what the penitents did when they heard the voice from within the Tree. Their senses told them — screamed at them — to eat the fruit held high above them. But they instead listened to the command of God, and walked on. We see in this tercet above that Dante’s will is being converted, joined with God’s own.

This demonstration causes the Angel to strike another P from Dante’s forehead. Dante then hears a voice saying that those whose hunger for righteousness (justice) exceeds their hunger for food are blessèd indeed. This, of course, comes from one of the Beatitudes: “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.” (Matthew 5:6)

The Lenten fast exists to train us to hunger for righteousness more than we hunger for food. The eels of Lake Bolsena can be as dangerous to our souls as the serpent in the Garden of Eden.

UPDATE: A few more thoughts on this. It occurs to me that in our Anglo-Saxon culture (versus, say, France’s or Italy’s), many people assume that enjoying fine food at all is a manifestation of gluttony. This isn’t true. If you watch the film Babette’s Feast, you see that eating simply did not save those pious Danes from sin, and in fact it was precisely feasting that caused them to repent, and to forgive their brothers and sisters. We Orthodox are instructed that fasting is fine, but never to forget that even the demons do without food; eating modestly does you no good if it’s not accompanied by a change of heart, and in fact if it makes you spiritually prideful, fasting can lead to sin.

Remember, sin is missing the mark by dwelling in a disordered relationship to what you love. For Statius, just freed from the terrace of Greed, it wasn’t hoarding money that earned him a place there, but being too free with spending it. I used to know a woman who would spend herself into deep debt every Christmas, buying expensive gifts for everyone she could think of. It was a kind of compulsion. She told herself that she was being especially generous, but it was pretty clear that her spending was all about satisfying her craving to be seen as generous. Other people were just pawns in her inner drama. I came to understand that the poor lady was so insecure that she thought buying expensive presents for everyone would assure her of their love. That may not have been greed as is commonly understood, but it was an extremely disordered relationship to money and material things.

Similarly with food. The cycle of fasting and feasting allows us to enjoy good food in the right season, and to put it aside in season. The thing is not to let it control us. An anorexic is as obsessed with food as an obese compulsive eater.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.