Purgatorio, Canto XVIII

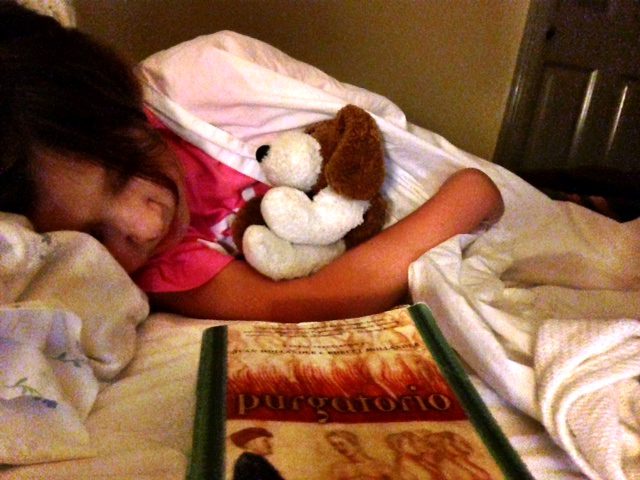

Just beyond the edge of the book, above, is my daughter Nora, and her stuffed doggie. Mama is out of town tonight, which means she gets to sleep in the big bed with Daddy. It’s been a hard day for her. There was nobody for her to play with this afternoon, and it made her think about how lonely she is. Her chin quivered as she tried to articulate what was in her heart.

“Do you want to get into Daddy’s lap and tell me about it?”

She bit her lip and nodded yes. I set my laptop down on the ottoman. She crawled up into the chair with me, and we had a talk. It culminated in me asking her, “Do you want to do something special with Daddy today?”

My daughter, who is seven, was working so hard to keep from crying that all she could do was nod nervously, her head buried in my shoulder.

“Let’s bake something together,” she said.

And so we did. We made a butter cake. I am not a very good baker — that’s Mama’s gift — but I did my best, and the cake turned out okay. The thing to know is that Nora turned out okay at the end, which was what was important. Doing something with Dad lifted her spirits, and made her forget her troubles.

I bring this up here, to preface our discussion about Canto XVIII, because here I am starting my daily Dante post just before midnight. When Nora and I finished baking the cake, it was time to go to vespers, after which there was a town party in front of the courthouse that I went to, and one thing led to another, and it’s midnight, and here we are.

I knew that I would be busy after vespers, which is why I was about to get started on the Canto XVIII post this afternoon, when sad little Nora ambled into the den. I work hard on my writing, really hard; I am not lazy about it at all. But that does not mean that I am not slothful. I am zealous for my writing, but far too often, I lack zeal for the other things in life that I should be doing — things like being with my kids. Truth to tell, I started to come up with a list of suggestions for things Nora could do while Daddy finished his Dante writing today. But thinking about this canto, in which Dante slogs through the terrace of Sloth, made me realize that my zeal for writing in this afternoon’s context was a form of Sloth.

That is, I had before me a weepy little girl who was lonely and who needed a friend, even if it was just her Daddy. She ought to have been my priority. I needed to have zeal to comfort her, and to show her that she is loved. I refused my usual impulse, which is to put writing first. In that sense, to have chosen to write instead of baking a butter cake with Nora would have been a form of laziness. As I write this now, I’m worn out, but I know that I won a small victory this afternoon over one of my worst dispositions. To have made my little girl happy, and to have spent that time baking with her, was gold. I forget that so often, and don’t see it because there is almost never a time when my mind is at rest. A man can be lazy as hell even if he’s working hard, if his zeal is misplaced — that is, if he does not have his loves rightly ordered.

Canto XVIII concerns Sloth, or as the Romans called it, acedia. Mazzotta says it is despondency, sluggishness, an “inversion of contemplation, tied to a sense of the loss of the outside world.” It is, he goes on, “indifference to anything outside of oneself.” Before reading the Commedia, I would not have thought of sloth in this way. My idea of slothfulness was the sluggard who won’t get off the couch and mow the lawn, or the teenager who would rather play video games than do his homework. It’s far more complicated than that, says Dante, who approaches the subject through a discussion with Virgil about love.

Dante asks his master to tell him what he meant in the last canto by the idea that love is the source of every virtue and every vice. Virgil explains that all actions begin with desire, but desires do not justify themselves:

It should be clear to you how blind

to truth those people are, who make the claims

that every love is, in itself, good love.

We can only judge which loves are good and which are bad by subjecting our desires to reason, which, says Virgil, “should defend the threshold of consent.” What a striking phrase. Virgil is saying in this canto that what makes us human is the power to rein in our desires by using our reason, and to refuse desires and impulses that tempt us before we assent to them with our will. In Orthodox Christian spirituality, these temptations are called logismoi. Here’s how they work on us, according to the Fathers of the Church cited by the pseudonymous Athonite monk Father Maximos in Kyriacos Markides’ wonderful book, The Mountain Of Silence:

- Assault – the logismoi first attacks a person’s mind

- Interaction – a person opens up a dialogue with the logismoi

- Consent – a person consents to do what the logismoi urges him to do

- Defeat – a person becomes hostage to the logismoi and finds it more difficult to resist

- Passion or Obsession – the logismoi becomes an entrenched reality within the nous of a person

According to Father Maximos, to consent to the logismoi is to cross over into sin. Do it often enough and you become defeated, and ultimately bound to that sin. Give your life over to it and you find yourself living in Hell in this life, or in the afterlife. The damned in Dante’s Inferno are people whose logismoi conquered their souls.

Last autumn, when I first began seriously dealing with my anxiety and depression — which is to say, trying to find my way out of the dark wood — my priest gave me a prayer rule that seemed staggeringly difficult to me. The gist of it was that I would spend an hour each day on my prayer rope, praying the Jesus Prayer: Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. If you do it as the Fathers instruct, you clear your mind of all extraneous thoughts, and focus on the presence of God. It’s hard to do. When I first began, I thought I was … well, I thought I was climbing a mountain, and doing so with numb hands and feet.

It was like this. A minute of two of praying attentively and then Lord Jesus Christ –hey, I’ve got to make sure I blog something about that thing I read this morning, and I’ve got to — have mercy on me, Lord Jesus Christ — I wonder if that book I ordered from Amazon is coming in today. Is Julie going to the post office, or am I? What’s for supper? Dang it, there I go again — have mercy on me — I’m so mad at that guy. What is his problem? I mean, how hard can it be to — crap, I messed up. Is it a sin to say crap when you pray? OK, let’s start over. Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God — squirrel!

Et cetera. You laugh, but that’s how it was. That’s how it still is, much of the time. But in those days, I was so easily thrown by my mind chasing thoughts like dogs chase squirrels in the park. The only way I managed to say my daily prayer rule was by sheer force of will. I prayed like that because my priest told me to, not because I wanted to. “How long do you want me to pray like this?” I said. “Every day for the rest of your life,” he said.

Brutal. But effective. Slowly, things began to happen inside me. The prayers were like a hatchet chipping away at ice. Things buried deeply began to surface. The Holy Spirit drew nearer. During this time, I was reading the Commedia, and when I came to the terrace of Sloth, I became profoundly aware of how much my slothful disposition hindered my spiritual progress. I have always been the kind of man who is eager to tackle personal challenges, provided I can find the answer in a book. This looks like a willingness to work hard, but it isn’t always that; in fact, it can be the opposite.

I’ve told this story before, but it’s worth repeating. In 1992, when I was living in Baton Rouge and had decided to become a Catholic, a colleague at work invited me to spend an afternoon with her working at the Missionaries of Charity soup kitchen downtown. That seemed like a Catholic thing to do, so I agreed. For hours, we washed pots and pans, and peeled potatoes. It bored the daylights out of me. I thought I was above that kind of thing. Maybe some ordinary convert could benefit from this, I thought, but the thing that I needed to be doing was reading theology.

There is nothing at all wrong with reading theology. But today, looking back on how my own highly intellectualized Catholic faith was shattered, I know that I would have been better off spending more time in the soup kitchen washing pots and pans and peeling potatoes. Likewise, last autumn, struggling to find a way out of the dark wood, I wanted to read books about it. But I didn’t have that liberty; I was told by my priest to pray, and to pray a lot, each day, meditatively. My desire was not to pray. My desire was to do anything else but sit still for an hour and focus on practicing the presence of God. But I did it.

It was the right thing to have done. Oh, I still struggle with it, and there are some days when my disordered zeal for writing or reading gets me to bedtime without having said my prayer rule. This is a hard habit to break. The things I love, I love intensely, so much so that it’s hard for me to be aware of how lost inside myself I’ve become in satisfying those desires. Here’s the thing: for me, the temptation is rarely toward loving bad things. It’s loving good things — intellection, including books and writing — out of turn. It is being insufficiently attentive to the things I am supposed to be zealous for, as opposed to the things I actually am zealous for.

Tonight I had a conversation with a neighbor. We talked about an old man of our mutual acquaintance, a gentleman who has been sick lately, and who may not have a lot longer to live. “I’ve got to get by and see him,” said my neighbor. “I swear I keep saying that, but it’s so damn hard to find time these days, you know? There’s just so much going on.”

I know. Believe me, I know. This is how I am too, every hour of every day. Let’s not fool ourselves, though: we will find time for the things we love. In this canto, Dante is telling us that we cannot allow ourselves to be driven by our desires alone, that to be passive in the face of raw desire is to fall into slavery to our cravings. We have free will, and we have reason. We have to identify the good and cultivate zeal for it — and that means training ourselves in asceticism. This is what Lent is especially for: disciplining our minds and our bodies so we can be free from the tyranny of restless, self-centered desire, and deepen our capacity for joy in satisfying right desires.

We will come to resemble what we love, and we will construct a habitus for ourselves that will make it easier for us to satisfy those desires. Reading Dante last year, especially this canto, I understood how much my own unhappiness emerged from my misplaced zeal. I wanted what I wanted, not what I needed, or ought to have wanted. The way out of the dark wood requires identifying the right things, then building your habitus so that you will find it easier to direct your will toward satisfying those desires.

What are the “right things” when there are rival goods? After all, there’s nothing wrong in principal with wanting to work hard at your vocation. Reading Dante and writing about it can be a very good thing. But not when it’s time to pray. Not when it’s time to put your little girl first. Not when it’s time to wash the pots and pans and peel the potatoes.

Near the end of this canto, Dante and Virgil see a mob of penitents rushing towards them. They are purging themselves of Sloth by running toward God, consumed now as they were not in their earthly life by desire for the Good, for the things of Heaven. Dante overhears the shades say:

“Faster, faster, we have no time to waste,

for time is love,” cried others from behind,

“strive to do good, that grace may bloom again.”

Time is love. Those tender, profound words resonate within me tonight, when I look over on the other side of my bed and see my sweet baby girl, and think about how much it meant to her that I said no to myself and my desire to spend the afternoon writing, and instead gave her an hour and a half of my afternoon today when she was hurting and needed a friend.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.