My Night At Vaclav Benda’s

If you read The Benedict Option, you’ll know the name of Vaclav Benda (d. 1999). He was a Czech mathematician, Roman Catholic, and leading anti-communist dissident. He went to jail along with Vaclav Havel. You can read more about him in this interview I published here last week with Flagg Taylor, an American academic who edited a collection of Benda’s essays, titled The Long Night of the Watchman.

From The Benedict Option, here’s a passage about him:

“A better system will not automatically ensure a better life,” [Vaclav] Havel goes on. “In fact the opposite is true: only by creating a better life can a better system be developed.”

The answer, then, is to create and support “parallel structures” in which the truth can be lived in community. Isn’t this a form of escapism, a retreat into a ghetto? Not at all, says Havel; a countercultural community that abdicated its responsibility to reach out to help others would end up being a “more sophisticated version of ‘living within a lie.'”

A good example of what this better life could look like comes from the late mathematician and dissident Václav Benda. A faithful Catholic, Benda believed that Communism maintained its iron grip on the people by isolating them, fragmenting their natural social bonds. The Czech regime severely punished the Catholic Church, driving many believers to privatize their faith, retreating behind the walls of their homes so as not to attract attention from the authorities.

Benda’s distinct contribution to the dissident movement was the idea of a “parallel polis” – a separate but porous society existing alongside the official Communist order. Says Flagg Taylor, an American political philosopher and expert on Czech dissident movements, “Benda’s point was that dissidents couldn’t simply protest the Communist government, but had to support positive engagement with the world.”

At serious risk to himself and his family (he and his wife had six children), Benda rejected ghettoization. He saw no possibility for collaboration with the Communists, but he also rejected quietism, considering it a failure to display proper Christian concern for justice, charity, and bearing evangelical witness to Christ in the public square. For Benda, Havel’s injunction to “live in truth” could only mean one thing: to live as a Christian in community.

Benda did not advocate retreat to a Christian ghetto. He insisted that the parallel polis must understand itself as fighting for “the preservation or the renewal of the national community in the widest sense of the word – along with the defense of all the values, institutions, and material conditions to which the existence of such a community is bound.

[Benda wrote:] I personally think that a no less effective, exceptionally painful, and in the short term practically irreparable way of eliminating the human race or individual nations would be a decline into barbarism, the abandonment of reason and learning, the loss of traditions and memory. The ruling regime – partly intentionally, partly thanks to its essentially nihilistic nature – has done everything it can to achieve that goal. The aim of independent citizens’ movements that try to create a parallel polis must be precisely the opposite: we must not be discouraged by previous failures, and we must consider the area of schooling and education as one of our main priorities.

From this perspective, the parallel polis is not about building a gated community for Christians but rather about establishing (or reestablishing) common practices and common institutions that can reverse the isolation and fragmentation of contemporary society. (In this we hear Brother Ignatius of Norcia’s call to have “borders ” – formal lines behind which we live to nurture our faith and culture – but to “push outwards, infinitely.” ) Benda wrote that the parallel polis’s ultimate political goals are “to return to truth and justice, to a meaningful order of values, [and] to value once more the inalienability of human dignity and the necessity for a sense of human community in mutual love and responsibility.”

In other words, dissident Christians should see their Benedict Option projects as building a better future not only for themselves but for everyone around them. That’s a grand vision, but Benda knew that most people weren’t interested in standing up for abstract causes that appealed only to intellectuals. He advocated practical actions that ordinary Czechs could do in their daily lives.

–

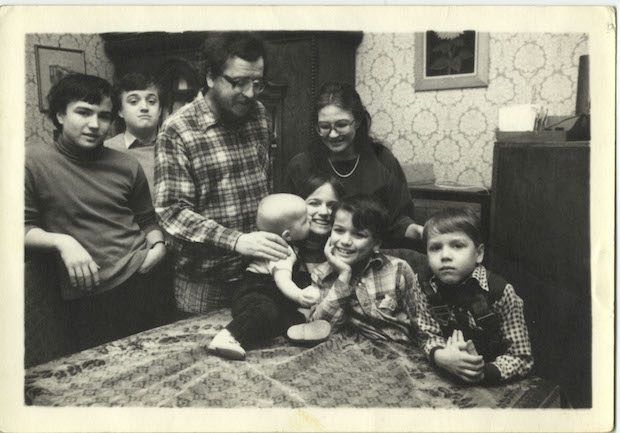

My Czech host, Father Stepan Smolen, arranged with the Benda family for me to visit the Prague apartment where Dr. Benda and his wife Kamila Bendova lived and raised their six children, now all adults with kids of their own. Kamila still lives there, and was able to gather five of the Benda children (and some of the Benda grandchildren) there in the family living room to meet me on Sunday night.

Last week, I published an interview with Flagg Taylor about Vaclav Benda and his work. Flagg once told me that the Bendas’ sense of Christian hospitality was such that they welcomed into their apartment dissidents, students, and ordinary people who wanted advice, counsel, or company in the long struggle against totalitarianism. And the other night, they welcomed me.

Father Stepan and I climbed two flights of stairs and stood outside the apartment door, looking at the nameplate. So this is the place.

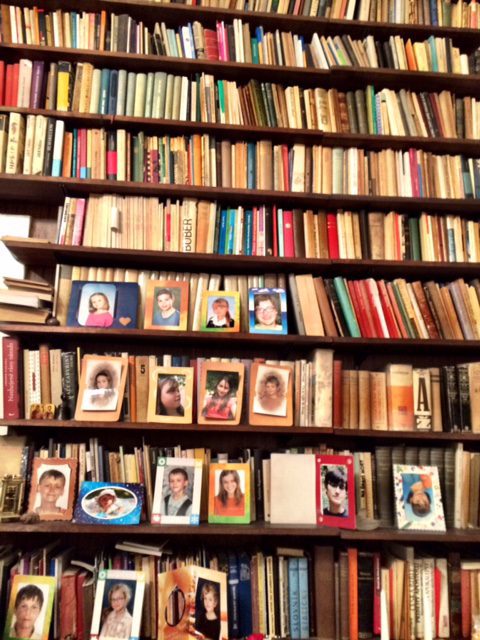

We were invited in by Patrick Benda, one of the six Benda children, all of whom are adults now. The apartment has high ceilings, and looks like exactly the kind of place you would expect a Prague intellectual to dwell. It was slightly shabby, in an utterly charming way. The walls are lined with tens of thousands of books. Here’s a shelf with photos of the grandchildren:

The sitting room where the Bendas held (and still hold) their seminars is dominated both by bookshelves and a massive crucifix:

Faith, family, and books: that’s what the Bendas are all about. This room is an icon of a way of living.

It is also a holy place, at least to me. Kamila told me on Sunday, “Because we lived just down the street from the place where the secret police tortured people, victims would often come here as soon as they were released, just to talk.” They knew there would be comfort at the Bendas’ house.

This is the house in which they raised their children. Kamila told me that she, a university professor of mathematics (like her late husband) read to her kids two to three hours every day.

“Every day?” I asked.

“Every day,” she said. It was part of their intellectual formation.

J.R.R. Tolkien and his Lord of the Rings was a cornerstone of the family’s imagination. I asked Kamila why.

“Because we knew Mordor was real. We felt that their story” — the hobbits and others resisting Mordor — “was our story too.”

She told me that as a mathematician, she knows that the ideology of science is what drives the world today. “Tolkien’s dragons are more realistic than a lot of things we have in this world,” she said, wisely.

We sat around in a big circle, the extended family (plus two other friends), Father Stepan, and I, talking about the Benedict Option, and about the family’s life under communism. The kids told me that their father raised them to be morally responsible in a particular way. He warned them that anything they might do to get in trouble — public drunkenness, for example — would be used by the government against him.

“That’s a heavy burden for a teenager to carry,” I said.

“We don’t see it that way,” said Martin Benda. “For us, it was a matter of being responsible to something outside of ourselves.”

Kamila talked about how she once received a letter from Vaclav from prison. In it, he wrote of the possibility that they would emigrate in exchange for early release.

“I wrote back to tell him no, that he would be better off staying in prison to fight for what we believe is true,” she told me.

Think of it: this woman was raising six kids all alone because her husband was a political prisoner. Yet she told him that the cause they served was more important than the relief of their suffering.

The kids told about how their parents vaccinated them against the disease of communist ideology by raising them to know that the things they heard at school and in the media were lies. In other words, Vaclav and Kamila were consciously countercultural, and understood that they had to impart the same sense to their children, to keep from losing their children to propaganda.

One of the Benda grandchildren said that her own father still does something like that: assigning the kids a certain book to read each month.

Vaclav Benda seems fearless, but Martin Benda said he was not a natural hero. Martin talked about a moment during the communist era in which his mother was late coming home, and he saw his father checking the window over and over, anticipating that she might have been arrested by the secret police.

“This is the moment when I started to admire my father even more,” said Martin. “That’s when I saw he was human. He was scared, but he did not want fear to master him.”

At one point, we were talking about the atmosphere of militant progressivism in the West, and how hard it is for Czechs to understand what’s happening in American universities. One of the Benda family friends, an academic, asked me if I had heard of Jordan B. Peterson. Yes, of course, I said.

“He is a miracle!” said this man.

Someone present explained that under communism, underground Christians looked with admiration to the West. But now they see so much decadence in the West, and don’t want it. Nor do they want to have anything to do with Putinism from the East — but this is what pro-Western Czech Christians often accuse them of. That is, if they don’t endorse whatever liberal theological fads are coming from the West, then that must mean (according to their enemies) that they are fellow travelers of Putinism. It’s not true, but that’s a particular struggle they face.

I kept thanking this amazing family for what they had given me through their father’s words and their own example. Patrick Benda told me that reading the new Czech translation of The Benedict Option inspired him to gather his wife and kids together, and tell them that they’re going to start praying together as a family. I thanked him for that, and said this is a good example of how we Christians today, building our parallel polis, need each other.

While I was sitting there, I was thinking about how much, much more this family has to teach us all about how to live faithfully in a world that is hostile to your Christian beliefs. I am sure this will not be the last time I see them, or visit their apartment, that shrine of faithful resistance and human decency. We in the West need to hear more, much more, from the wife and children of Vaclav Benda, the watchman who kept faith through the long night. Spending that evening with them, in their cavernous, book-filled apartment, was one of the great privileges of my life. I am deeply, deeply grateful to them all.

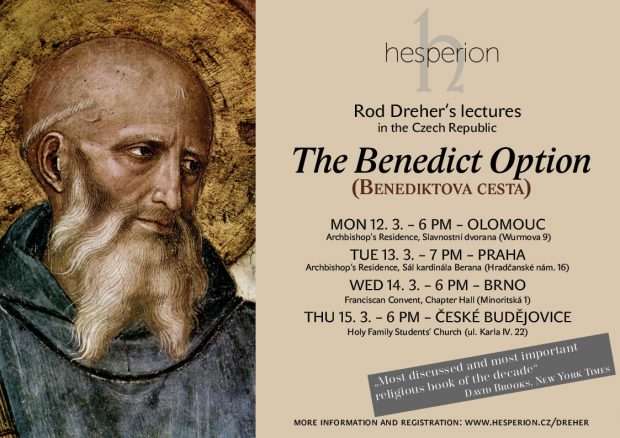

Hey readers, if any of you are in Prague, I’m giving a free Ben Op lecture in Prague tonight (March 13) at the Archbishop’s Residence. Come say hello!

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.