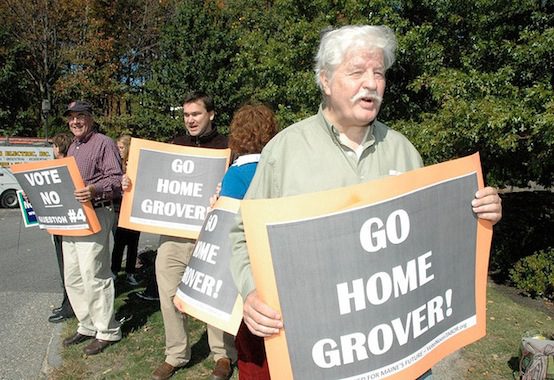

Debating the Merits of the Norquist Pledge

At the Americans for Tax Reform website, Paul Blair takes issue with my recent criticisms of the Grover Norquist-spearheaded Taxpayer Protection Pledge.

Let me clarify one thing before I wade into the specifics of Blair’s response. He signs off by saying I should “stop searching for a singular mechanism by which to prevent all that is ‘bad’ in Washington. No such force exists.” Hear, hear! I agree implicitly with that statement. And when I wrote about the Coalition to Reduce Spending’s new, supercharged pledge, I was praising it for recognizing that an “unintended consequence” of the Norquist pledge was to increase lawmakers’ reliance on deficit-spending.

Nonetheless I concluded the pledge is as misguided as Norquist’s:

For the record, I think a statutorily required balanced budget is a stupididea, and that anyone who signs this new pledge is terrifically insane and should therefore be disqualified from public office. Other than that, it’s a significant improvement on Norquist’s porous pledge.

Regarding that last line, I hope it’s clear to the reader that, like Robin Williams in “Good Will Hunting,” I was being “ironical.”

Back to Blair, who writes, “Galupo misses the mark, whether it is on purpose or by mistake, for a number of reasons. First, the Pledge is one protection for taxpayers against an increased financial burden of a growing federal government.” That’s a pretty astonishing assertion, when you think about it. 1) Why shouldn’t taxpayers be responsible for a “growing federal government”; and 2) Who else ultimately could be responsible for it? It is not, after all, a foreign government or some exogenous entity that has attached itself to the body politic.

The Pledge was not simply a means to “holding the line on taxes,” as Blair argues. It was supposed to “starve the beast” — that is, compel lawmakers to reduce federal outlays. Blair insists it’s not the Pledge’s fault that politicians keep spending: “It is but one tool in the shed of protections against a government that demands you fork over more of your hard earned cash to pay for its overspending problem.”

But what if Norquist’s tool hasn’t been just ineffectual? What if it actually made the problem worse?

This gets to the core of why I believe the Norquist pledge is an impediment to reform. Blair writes, “The biggest failure of Galupo’s critique of the Pledge is his attempt to make a connection between holding the line on taxes as an excuse for increased spending. By no logic are they connected.” Really? No logic at all? Ten dollars of spending for every six dollars in taxes hasn’t made big government feel artificially cheap, as George F. Will observed on ABC’s “This Week”?

As the late William A. Niskansen reluctantly concluded:

If our political system then leads to decisions that roughly reflect voter references, the longer-term challenge for those of us who favor limited constitutional government is to try to convince voters to reduce their demand for the services financed by federal spending. Until that time, some increase in federal taxes appears to be a necessary part of a fiscal policy to balance the budget.

In a 2006 profile of Niskansen, Jonathan Rauch argued similarly:

[C]onservatives who are serious about halting or reversing the dizzying Bush-era expansion of government—if there are any such conservatives, something of an open question these days—should stop defending Bush’s tax cuts. Instead, they should be talking about raising taxes to at least 19 percent of the GDP. Voters will not shrink Big Government until they feel the pinch of its true cost.

Third, the most effective constraint of all is to raise taxes and cut spending: exactly the sort of anti-deficit package that anti-tax conservatives pummeled the first President Bush and President Clinton for approving, and exactly the sort of package that the current President Bush and his anti-tax allies are sworn to block.

The conservative movement is in no position to accept or even acknowledge those implications, now that tax cutting has become the long pole in the Republican tent. Therein lies the element of tragedy. By turning a limited-government movement into an anti-tax movement, conservatism has effectively gone into business with the Big Government that it claims to oppose. It is not starving the beast. It is fueling the beast’s appetite. And the beast has a credit card.

That’s right: the beast has a credit card. And Grover Norquist — inadvertently — extended its credit limit.