Christianity’s American Decline

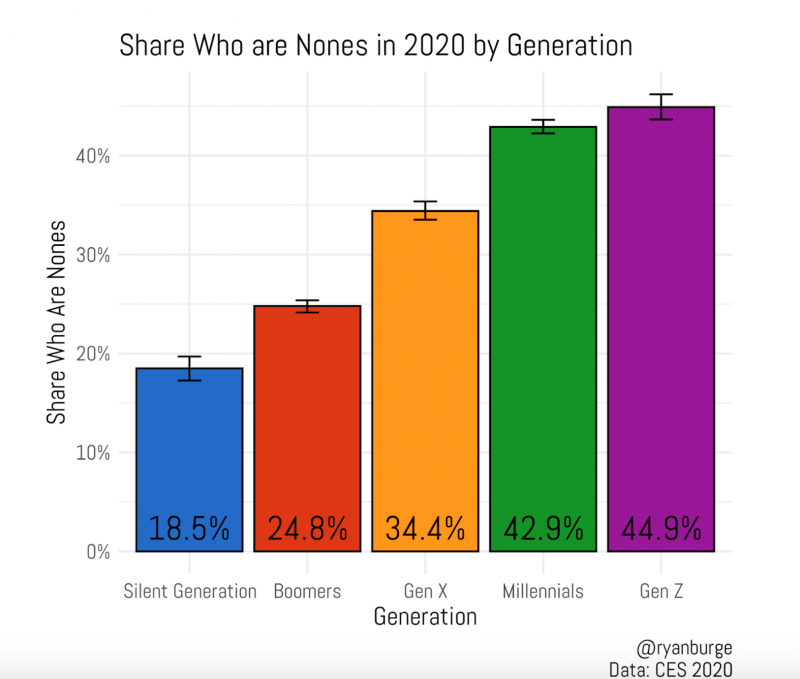

For people who care about religion in America, Ryan Burge is a must-follow on Twitter. He’s a political scientist and a Baptist pastor, so he knows faith both professionally and personally. In his latest article, he highlights what he says “may be the biggest cultural shift in our lifetimes”: the exodus of Generation Z (those born 1996 and later) out of religion. Take a look at this chart of his:

He says that Generation Z is already the least religious generation in US history — and their leaving the faith (or never acquiring it in the first place) is the main driver of America’s secularization:

Consider this: every day in America, hundreds of people from the Silent Generation (19% nones) and the Boomers (25% nones) die off and are replaced by members of Generation Z (45% nones) having their eighteenth birthday. This, by itself, will make the United States much less religious in 2030 than it was in 2020.

This is going to have a big political effect too. Look:

The conservative Nones doubled (from 2017) in just three years! Burge writes:

There’s clear evidence that those who identify as politically liberal are much more likely to say that they have no religious affiliation. In fact, in every survey from 2016 through 2020, at least half of liberal members of Gen Z say that they are atheists, agnostics, or nothing in particular. Among conservatives, the percentages are much smaller but they are growing. In both 2016 and 2017, less than 20% of conservatives said they were nones. That has steadily crept up to 29% in 2020.

This is something to keep an eye on going forward. Up to this point, the linkages between liberal politics and religious nones have been incredibly strong. But, with an increasing number of young conservatives indicating that they have no religious affiliation, they will be in a tough spot on election day. The Republican Party is overwhelmingly Christian and most national politicians pander to this base on a consistent basis. How the GOP pivots to attract and retain young nones will be crucial if they want to be a viable national party in the future.

I would like to know what separates conservative Nones from political conservative who are religious. That is, on what political points do they differ. Are the Nones pro-choice, for example? I’m guessing they are probably fine with gay rights, though I don’t know what they think about trans; maybe they’re for it. What, exactly, makes them conservative? I would guess — but it’s only that — that it’s anti-wokeness. I was at an event here in Budapest yesterday in which a friend of mine, a secular academic, said, “My conservatism boils down to this: I’m anti-woke.” I think that is a perfectly viable point of view, and probably one that a lot of secular people who identify as conservative share. Any of you readers of this blog who are secular conservatives, please say in the comments where you differ politically from conservatives who are religious.

Burge is correct that we on the Right are going to have to figure out some way to defend what religious conservative voters care about without alienating secular conservative voters. Hungary is a rather secular country, but one that is socially conservative. People generally hate wokeness, and they are mostly against LGBT rights, not out of religious conviction, but because they believe that the traditional family is a model worth affirming and even privileging. In the US, opposition to gay rights is tightly affiliated with religious belief, but that is 100 percent not the case in Hungary. This makes me wonder if there is a significant number of Americans who are more or less hostile to LGBT rights, but who consider themselves secular. I rather doubt it, but I do wonder.

If you would like to see Burge presenting his findings in a 15-minute TV interview, check him out from last week on Raymond Arroyo’s EWTN show:

Whatever the political fallout, these new data confirm the existential crisis for Christians that I wrote about in The Benedict Option. From the introduction:

I have written The Benedict Option to wake up the church, and to encourage it to act to strengthen itself, while there is still time. If we want to survive, we have to return to the roots of our faith, both in thought and in deed. We are going to have to learn habits of the heart forgotten by believers in the West. We are going to have to change our lives, and our approach to life, in radical ways. In short, we are going to have to be the church, without compromise, no matter what it costs.

This book does not offer a political agenda. Nor is it a spiritual how-to manual, nor a standard decline-and-fall lament. True, it offers a critique of modern culture from a traditional Christian point of view, but more important, it tells the stories of conservative Christians who are pioneering creative ways to live out the faith joyfully and counterculturally in these darkening days. My hope is that you will be inspired by them, and collaborate with like-minded Christians in your local area to construct responses to the real world challenges faced by the church. If the salt is not to lose its savor, we have to act. The hour is late. This is not a drill.

Alasdair MacIntyre said that we await “a new—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.” The philosopher meant an inspired, creative leader who will pioneer a way to live the tradition in community, so that it can survive through a time of great testing. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI foretells a world in which the church will live in small circles of committed believers who live the faith intensely, and who will have to be somewhat cut off from mainstream society for the sake of holding on to the truth. Read this book, learn from the people you meet in it, and be inspired by the testimony of the lives of the monks. Let them all speak to your heart and mind, then get active locally to strengthen yourself, your family, your church, your school, and your community.

In the first part of this book, I will define the challenge of post-Christian America as I see it. I will explore the philosophical and theological roots of our society’s fragmentation, and I will explain how the Christian virtues embodied in the sixth-century Rule of St. Benedict, a monastic guidebook that played a powerful role in preserving Christian culture throughout the so-called Dark Ages, can help all believers today.

In the second part, I will discuss how the way of Christian living prescribed by the Rule can be adapted to the lives of modern lay Christians of all churches and confessions. The Rule offers insights in how to approach politics, faith, family, community, education, and work. I will detail how they manifest themselves in the lives of a diverse number of Christians, who have lessons to teach the entire church. Finally, I will consider the critical importance of believers thinking and acting radically in the face of the two most powerful phenomena directing contemporary life and pulverizing the church’s foundations: sex and technology.

In the end, I hope you will agree with me that Christians today are in a time of decision. The choices we make today have consequences for lives of our descendants, our nation, and our civilization. Jesus Christ promised that the gates of Hell would not prevail against His church, but He did not promise that Hell would not prevail against His church in the West. That depends on us, and the choices we make right here, right now.

I invite you, the reader, to keep in mind as you make your way through these pages that maybe, just maybe, the new and quite different Benedict that God is calling to revive and strengthen His church is . . . you.

From Chapter One:

Not only have we lost the public square, but the supposed high ground of our churches is no safe place either. So what if those around us don’t share our morality? We can still retain our faith and teaching within the walls of our churches, we may think, but that’s placing unwarranted confidence in the health of our religious institutions. The changes that have overtaken the West in modern times have revolutionized everything, even the church, which no longer forms souls, but caters to selves. As conservative Anglican theologian Ephraim Radner has said, “There is no safe place in the world or in our churches within which to be a Christian. It is a new epoch.”

Don’t be fooled by the large number of churches you see today. Unprecedented numbers of young adult Americans say they have no religious affiliation at all. According to the Pew Research Center, one in three 18-to-29 year olds have put religion aside, if they ever picked it up in the first place. If the demographic trends continue, our churches will soon be empty.

Even more troubling, many of the churches that do stay open will have been hollowed out by a sneaky kind of secularism to the point where the “Christianity” taught there is devoid of power and life. It has already happened in most of them. In 2005, sociologists Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton examined the religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers from a wide variety of backgrounds. What they found was that in most cases, teenagers adhered to a mushy pseudo-religion the researchers deemed Moralistic Therapeutic Deism (MTD). MTD has five basic tenets:

• A God exists who created and orders the world and watches over human life on earth.

• God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other, as taught in the Bible and by most world religions.

• The central goal of life is to be happy and to feel good about oneself.

• God does not need to be particularly involved in one’s life except when he is needed to resolve a problem.

• Good people go to heaven when they die.This creed, they found, is especially prominent among Catholic and Mainline Protestant teenagers. Evangelical teenagers fared measurably better, but were still far from historic Biblical orthodoxy. Smith and Denton claimed that MTD is colonizing existing Christian churches, destroying Biblical Christianity from within, and replacing it with a pseudo-Christianity that is “only tenuously connected to the actual historical Christian tradition.”

MTD is not entirely wrong. After all, God does exist, and He does want us to be good. The problem with MTD, in both its progressive and conservative versions, is that it’s mostly about improving one’s self-esteem and subjective happiness, and getting along well with others. It has little to do with the Christianity of Scripture and tradition, which teaches repentance, self-sacrificial love, and purity of heart, and commends suffering—the Way of the Cross—as the pathway to God. Though superficially Christian, MTD is the natural religion of a culture that worships the Self and material comfort.

As bleak as Christian Smith’s 2005 findings were, his follow-up research, published in 2009, was even grimmer. Surveying the moral beliefs of 18 to 23 year olds, Smith and his colleagues found that only forty percent of young Christians surveyed by Smith’s team said that their personal moral beliefs were grounded in the Bible. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the beliefs of even these faithful are Biblically coherent. Many of these “Christians” are actually committed moral individualists who neither know nor practice a coherent Bible-based morality.

An astonishing 61 percent of the emerging adults had no moral problem at all with materialism and consumerism. An added 30 percent expressed some qualms, but figured it was not worth worrying about. In this view, say Smith and his team, “all that society is, apparently, is a collection of autonomous individuals out to enjoy life.” These are not bad people. Rather, they are young adults who had been terribly failed by family, church, and the other institutions that formed—or rather, failed to form—their consciences and their imaginations. MTD is not simply the de facto religion of American teenagers, but also of American adults. To a remarkable degree, teenagers have adopted the religious attitudes of their parents. We have been an MTD nation for some time now, though that may have been disguised.

“America has lived a long time off its thin Christian veneer, partly necessitated by the Cold War,” Smith told me in an interview. “That is all finally being stripped away by the combination of mass consumer capitalism and liberal individualism.”

The data from Smith and other researchers make clear what so many of us are desperate to deny: the flood is rising to the rafters in the American church. Every single congregation in America must ask itself if it has compromised so much with the world that it has been compromised in its faithfulness. Is the Christianity we have been living out in our families, congregations, and communities a means of deeper conversion, or does it function as a vaccination against taking faith with the seriousness the Gospel demands?

Nobody but the most deluded of the old-school Religious Right believes that this cultural revolution can be turned back. The wave cannot be stopped, only ridden. With a few exceptions, conservative Christian political activists are as ineffective as White Russian exiles, drinking tea from samovars in their Paris drawing rooms, plotting the restoration of the monarchy. One wishes them well, but knows deep down that they are not the future.

Americans cannot stand to contemplate defeat, or to accept limits of any kind. But American Christians are going to have to come to terms with the brute fact that we live in a culture, one in which our beliefs make increasingly little sense. We speak a language that the world more and more either cannot hear or finds offensive to its ears.

Could it be that the best way to fight the flood is to . . . stop fighting the flood? That is, to quit piling up sandbags and to build an ark in which to shelter until the water recedes and we can put our feet on dry land again? Rather than wasting energy and resources fighting unwinnable political battles, we should instead work on building communities, institutions, and networks of resistance that can outwit, outlast, and eventually overcome the occupation.Fear not! We have been in a place like this before. In the first centuries of Christianity, the early Church survived and grew under Roman persecution, and later after the collapse of the Empire in the West. We latter-day Christians must learn from their example—and particularly from the example of St. Benedict.

Four years since its publication, evidence mounts that the message of The Benedict Option — its diagnosis of the crisis, and its alarming conclusions — was spot-on. Last autumn, I met a Portland megachurch pastor at a Nashville conference who told me that when the book first came out, people in his circles read it, but thought it was too alarmist. “Now we are living its reality,” he told me.

We all are — it has just arrived in some places sooner than others. The warning that Father Cassian Folsom, the Benedictine monk who was at the time the prior of the Norcia monastery, gave me is even more potent today: if any Christian family wants to make it through what’s coming, they are going to have to do some form of the Benedict Option.

It is past time to stop falling back on this false dichotomy of being in the world vs. fleeing it. As I make very clear in the book, we lay Christians are generally called to be in the world. But if we are going to be in this post-Christian (and increasingly anti-Christian) world and hold on to our faith, we are going to have to spend more time away from the world, and focus more intensely on what makes us unlike the world. The book explains this.

The signs are very, very clear: America is leaving Christianity behind. We are not going to vote our way out of this crisis. Christian pastors and Christian laymen who comfort themselves with the idea that we can keep living as we have always done, and hope for the best, are lying to themselves. I wish it were otherwise, but this is where we are. The time for clerical Grindr games, or pastoral preoccupations with worldly politics, or happy-clappy religiosity is over. We are in a fight for our religious lives. Souls are at stake: the souls of young people today, and the souls of those yet to be born who might never have the faith presented to them, because they will not have grown up in a home where it exists. It can’t get more serious than this, folks.