‘Asymmetrical Multiculturalism’

Reader Jonah writes:

On Sunday, my wife had brunch with several friends who have children in kindergarten or early elementary school. All of them live in a nearby densely packed suburb here in our county, which is a “sanctuary” for illegal immigrants in all but name.

Every single friend confessed that they and their husbands plan to sell their homes and move to other areas of the county because “the schools have gotten so bad.”

All of these nice, liberal-signaling people are uprooting their entire lives to get their kids into better schools, but they can never speak the reason aloud. The schools turning bad is force majeure, you see, like a hurricane or an earthquake, but with utterly mysterious origins, like a pulse from another dimension that leaves the world’s top scientists scratching their heads.

It’s just so weird. White, Asian, and black people can haul ass away from schools that are overcrowded with Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan immigrants, schools that take tax money to implement programs for youth gang interdiction, and they can speak openly about the fact that they’re leaving, but nobody is allowed to utter why they’re leaving. It’s absolutely verboten to suggest that concentrating impoverished immigrants in certain places even sometimes has social and cultural down sides. We can’t even suggest that local politicians have mismanaged the influx of immigrants. We’re only allowed to reiterate that immigrants add colorful threads to the diverse multicultural tapestry of our community. We’re not allowed to say that schools are less safe, violent crime has doubled, and we have a gang problem we didn’t used to have—not even at brunch with friends, as if there are no options between tight restrictions and open borders.

This is a super-bourgeois observation — I mean that in the sense that what he’s talking about is the code among college-educated middle class white people. Funny story: once, about 20 years ago, I was visiting my folks down in Louisiana. One day, when I drove in from town, a mill worker from down the road had stopped by, and was on my mom and dad’s front porch visiting. He hardly knew me; I was Ray and Dot’s son who had moved away and was in the media. I walked in mid-conversation, and found this mill worker talking in a strange way about some big problem at the mill, and the Democrats this, and the Democrats that. I couldn’t make sense out of what he was saying.

After he left, I asked my folks what on earth the Democratic Party had to do with the problems at the mill. They all laughed. My sister, who had been sitting there listening to it, said that “Democrats” is the code white working-class people like the mill worker use to talk about black people when they’re in the presence of white outsiders who are likely to judge them as racists.

I can’t remember any details of what the mill worker said, but I do recall thinking clearly at the time that even if that particular mill worker was a racist, substituting “black co-workers” for “Democrats” in his narrative that afternoon wouldn’t have made it racist. The point was that this mill worker assumed that because I was white, and college-educated, and lived in the big city, that I hated people like him, and was prepared to judge any criticism of black people at all as racist. He wasn’t going to stop telling his story to my Louisiana family just because the city boy he barely knew had walked up … so he code-switched.

(And what a code word! This man, who is probably retired now, if he’s still alive, worked in a paper mill and lived in a trailer in rural south Louisiana — yet for him and his social circle, the word “Democrats” was synonymous with “blacks.” A generation earlier — my dad’s generation — all white men like him would have been registered Democrats. If that man is alive today, I bet he’s a Trump Republican, and was finally glad to have a Republican to vote for who sounds like him.)

To be honest, that simple mill worker was right to be wary about me, a middle-class urban white guy, for the same reason that reader Jonah says in his comment.

What Jonah is talking about is what the UK academic Eric Kaufmann calls “asymmetrical multiculturalism.” Park MacDougald writes about the idea here in New York magazine. MacDougald opens by talking about how thinkers and commentators on the left decry white identity, while their counterparts on the right respond by rejecting identity politics of all kinds. More:

This bipartisan aversion to white identity is the target of Whiteshift, a fascinating new book by the political scientist Eric Kaufmann. Kaufmann claims that despite our best collective efforts to repress the topic, white identity concerns are already in the process of reshaping politics across the West. Migration-driven demographic change is polarizing white electorates, pitting group-oriented whites determined to resist their decline against cosmopolitan whites who accept or even cheer it, leading to the liberal-internationalist versus populist-nationalist split we see in nearly every Western country. More controversially, Kaufmann argues that the identity-based concerns of whites who oppose or fear their demographic decline should not be considered racist, and that it is neither possible nor desirable for the mainstream to suppress or condemn them. Instead of assuming that all political expressions of white identity are motivated by prejudice, Kaufmann calls for a new “‘cultural contract,’ in which everyone,” white and nonwhite, “gets to have a secure, culturally rich ethnic identity as well as a thin, culturally neutral and future-oriented national identity.”

MacDougald notes that Kaufmann contends the future of the West is going to bring a lot more interethnic marriage, as a result of immigration. Kaufmann, who is one-quarter Latino and one-quarter Asian, says the he himself is an example of the future. More:

In the meantime, however, he predicts that the conflict between those who wish to slow this transformation and those who wish to accelerate it will become the defining cleavage of Western politics.

In fact, at the center of Whiteshift is the argument that this conflict is already reshaping our politics. In Kaufmann’s view, white identity concerns, not economics, are behind the rise of right-wing populism. For all the attempts to explain populism as a backlash to inequality or a revolt of the losers of globalization, Kaufmann, drawing on his own research and that of colleagues such as Karen Stenner and Ashley Jardina, sees it as an expression of conservative white opposition to demographic change. Among whites in the United States, for instance, support for Trump was strongly predicted by psychological conservatism and authoritarianism, white identity and ethnic consciousness, and opposition to immigration. (Similar measures predicted support for Brexit in the U.K.) Kaufmann also cites suggestive research not directly related to the election, such as Maureen Craig and Jennifer Richeson’s finding that whites, after reading a passage about their demographic decline, displayed greater levels of in-group bias and support for the GOP.

One more:

Kaufmann is not the first to suggest that populism is an expression of white demographic anxiety. Versions of this argument have been made before, often becoming, in simplified form, the basis of a morality tale in which Trump voters are racist authoritarians whose only real goal is to maintain white supremacy. Yet Kaufmann believes that it is perfectly legitimate for whites to prefer immigration restriction for cultural reasons, and criticizes the expansive elite anti-racism norms that see this preference as racist. These norms, according to Kaufmann, make it difficult for mainstream politicians to respond to their voters’ actual concerns, producing a vast unmet demand for restrictionist policies that the populist right is well-positioned to meet. They also lead restrictionist voters and politicians, who oppose immigration for cultural reasons but fear accusations of racism, to invent spurious economic or security rationales to justify their preferences. “Paradoxically,” Kaufmann writes, “it becomes more acceptable to complain about immigrant crime, welfare dependency, terrorism or wage competition than to voice a sense of loss and anxiety about the decline of one’s group or a white-Christian tradition of nationhood.” Consider the debate over Trump’s border wall. The president has cited terrorism, drug and human trafficking, and immigrant crime as reasons to build the wall, tarring immigrants as criminals while offering a policy that would do little to address his stated concerns. It would be far better, in Kaufmann’s view, if the president — or at least, the more intelligent of his advisers and supporters — were just to admit that what what really made them anxious about immigration was demographic change.

I strongly encourage you to read the whole thing. Every paragraph is meaty and challenging. The book is Whiteshift.

MacDougald says Kaufmann, a sociologist at the University of London’s Birkbeck College, believes that both the identity-politics Left and the anti-identity-politics Right, are going at the social and political questions wrong.

The Left observes what Kaufmann calls “asymmetrical multiculturalism” — the belief that every racial/ethnic identity should be asserted and celebrated, except white identity. This, says Kaufmann, is a strategy that works for “psychological liberals,” but not for everybody else. Asymmetrical multiculturalism is at work in the story reader Jonah told about the middle-class white people who are desperate to get away from bad schools that got that way for reasons that those white people cannot even bring themselves to speak about among each other. This is distorting, and destructive.

But the Right plays its own version of denial, in Kaufmann’s view, with its belief that all identity politics are immoral. They do this in part because they are trying to maintain moral symmetry: if it’s wrong for white people to identify with their race, and to pursue political policies based on what’s good for their race, then it must also be wrong for every ethnic group to behave that way. The problem with this, says Kaufmann, is that it’s unnatural and just plain wrong. People of various “tribes” do this all the time, and though it obviously can be abused, it’s better (in Kaufmann’s view) to allow everybody to engage in a limited version of this, rather than to deny that it has any validity at all. If whites were allowed by the popular culture to think of themselves collectively in the way blacks, Latinos, Asians, and others are allowed to think of themselves, then perhaps non-liberal whites would recognize that some identity politics claims made by racial minorities are valid and important to recognize.

That’s the theory, anyway.

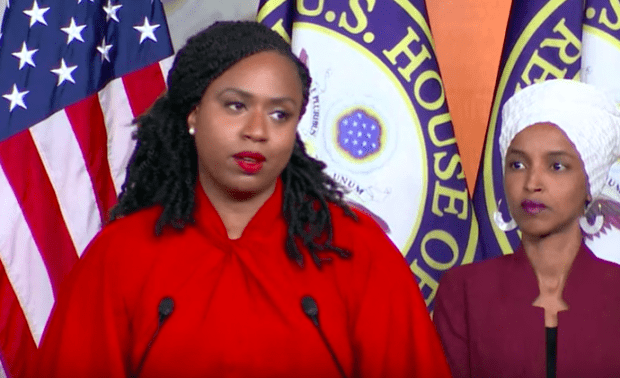

Imagine what would happen if a Republican Congressman said about whites in politics what Mod Squad member Rep. Ayanna Presley said about gays, Muslims, and racial minorities in politics last week:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PUFJNI-A63A]

We would have a national media freakout on our hands. Anderson Cooper would interview a loaf of Wonder Bread and a jar of mayonnaise on live TV. Frankly, I find what Pressley is doing here — policing the boundaries of minority politics — to be repulsive, and I would find it repulsive if a white Republican Congressman did it for whites. The fact, though, that this is considered normal behavior by progressives who are racial minorities, but absolutely unthinkable for white conservatives, testifies to the power of asymmetrical multiculturalism.

Speaking from my own experience, when I think of whites being allowed to think about race, identity, and politics in the same way as racial minorities, I think about segregationists like the late Gov. Lester Maddox, who said on that Dick Cavett interview I mentioned yesterday that he supports black folks who believe in defending the preservation of their race, and white folks who believe in the same thing. In 1970, when he said it. that was a transparently a fraudulently fair-minded argument for maintaining white supremacy.

Would it be today? Perhaps, but much less so. What about circa 2040, when America becomes a majority-minority society?

I hate asymmetrical multiculturalism because in the world I live in — among media, academic, and cultural elites, broadly speaking — it is a strategy for disempowering and marginalizing people on the basis of race, sexuality, and religious belief, and psychologically disarming any instinct for self-preservation among them. I’m one of those right wingers that Eric Kaufmann says is mistaken in his opposition to all identity politics.

He might be right about me and my kind. One thing is for sure, though: in this time of turmoil and social transition, conservatives who think like me are going to lose ground to white right-wingers — not conservatives; right wingers — who think like the black Democrat Ayanna Presley. Who, by the way, has more in common with Lester Maddox than she could possibly understand. In that sense, Donald Trump is arguably playing by the rules Pressley, Omar, and the asymmetrical multiculturalists of the American Left observe — and that’s why they hate him so much. I don’t think Trump is any kind of political genius, but perhaps it takes someone as uncultured and unformed by the norms of his economic class to reject the asymmetrical multiculturalism that is received without question by our elites.