Slavery Reparations Won’t Change the Past. What About the Future?

Congress decided yet again to hold a hearing on slavery reparations, this one on June 19. There’s a campaign to be waged against Donald Trump, after all.

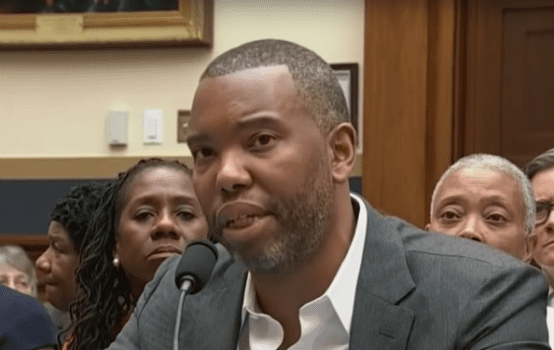

The hearing featured intellectuals like Ta-Nehisi Coates and second-tier celebs like Danny Glover laying out a long history of horrors. What was missing was what has been missing since 19th-century efforts to pay freed slaves failed directly: how handing out money is supposed to fix anything. It will not change the past and no one has made clear how it will positively affect the future.

Reparations in their earliest form were proposed after the Civil War, when the government sought to give 40 acres of land and a mule to each freed slave. That idea died with Abraham Lincoln, though the concept never really went away (old age pensions were considered for former slaves in the 1880s). Reparations took on new life when, in every Congress from 1989 until his retirement in 2017, Representative John Conyers introduced a bill, HR 40, concerning reparations. The numerical designation itself was a reference to the original failed attempt with those 40 acres.

Now nearly every 2020 Democratic candidate except Joe Biden supports some version of the bill’s basic goal: a commission to study the idea of reparations. Any actual payments are a long time coming. But in a Not Trump campaign, spotlighting divisive racial issues that no one will actually have to act on is a key strategy.

At the most recent hearings, Coates framed reparations around the continued impact of slavery: “Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy.” Coates became famous for writing an essay, “The Case for Reparations,” in 2014. It is typically cited as a foundational text, and as such formed the core of Coates’ testimony. Upon examination today, however, it seems more intent on prioritizing moral purity and ideology above making any “case.” It conflates historic lynchings with modern injustices—”land taken from black families has become a country club”—where the reader is left to assume that blacks are not welcome.

Coates and others in this debate find an awful lot of racism in a country that just a few years ago twice elected a black man to the presidency. To explain away Barack Obama—whose existence upsets an otherwise continuous recalibration of suffering from the plantations to Colin Kaepernick—Coates claims, without evidence, that “in the contest of upward mobility, Barack and Michelle Obama won by being twice as good and enduring twice as much.” He gave no details about Barack enduring “twice as much” while growing up in the suburbs, attending Hawaii’s most expensive private prep school, then Columbia University, then Harvard Law School, then becoming a member of the Senate.

But we get it: Coates’ America is and has always been based on black and white, even as he strains to connect the horrors of the Middle Passage with whatever struggles they imagine Obama went through at Harvard. But Coates’ essay is “The Case for Reparations.” You would expect it to make one beyond our relatives suffered, we still suffer in ways connected to that, so white people give us something.

Yet Coates stops there, angry as hell, as do others who argue for reparations. His attempts to move away from the emotional and ideological towards something concrete—exactly what paying reparations would accomplish—hit a dead end. At one point, he claims that reparations would close the wealth gap between blacks and whites, a naive statement given that, since 1980, incomes of the very rich (the 0.1 percent) grew 400 percent faster than the economy, while the other 90 percent (of all races) fell behind.

Coates defines reparations as “the full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences.” Another proponent mused about the “liberating power that can be unleashed by this kind of introspection,” as if calling for a Ken Burns-Spike Lee Netflix series.

If reparations really are some sort of delayed moral rebalancing, then the idea is cheapened when it comes with an Amazon gift card (others have suggested zero-interest loans for black home buyers, free college tuition, money to black-owned businesses, and so on). Yet Georgetown University giving scholarships to African-American kids, funded by a tuition increase, all to make up for the school’s having once owned slaves, seems aimed more at making Georgetown feel less guilty (and silencing its critics) than any significant righting of historical wrongs. A token gesture?

The idea is further cheapened when people argue against anything that might be due to anyone else, that this must be a black thing or nothing. So leave out the others who sleep on a mountain of bones: Chinese worked to death building the railroads, Irish laborers killed by malaria in the New Orleans swamps, Jews denied asylum and sent back to the Holocaust, Italian child laborers in the textile mills, Appalachians poisoned in the coal mines, generations of underpaid women denied the vote, and Hispanics relegated to inner-city slums.

Crudely expressed as “my ancestors didn’t own slaves and yours didn’t pick cotton,” the reality is that the horrors of slavery were committed by a limited number of whites. Only about 5 percent of the slaves taken from Africa ended up in America. Less than one quarter of white Southerners owned slaves, with half of those holding fewer than five. The majority of Americans had nothing to do with slavery, and many trace their lineage to those who arrived after any of the discriminatory acts Coates testified about.

Reality betrays the modern-day rebuttal: that everyone is in on it because slavery was the prime mover to discrimination of blacks, and all whites have profited from it. While percentage-wise more blacks live in poverty today than whites, that means little in terms of actual lives when the mouths to feed are counted: numbering 14 million, twice as many whites are impoverished in America. It is hard to claim that “white privilege” is spread broadly across our economy.

Tallies of suffering aside, we are still left with the core question: what is the value of paying reparations, to one group or to all of them? The self-referential truth is that reparations will help heal us—restorative justice. The history is far less clear.

Following World War II, Congress created the Indian Claims Commission to pay reparations for seized land. Any good intentions were lost among the lack of accurate records, and in the end the Commission produced 43 volumes of decisions that showed they paid out less than $1,000 for each Native American. But double, triple, multiply times 10 the amount—could you still argue that those reparations would have changed much about the state of Native Americans? Percentage-wise, more Native Americans today live in poverty than blacks. The suicide rate for Native Americans is 3.5 times higher than for other groups, due to poverty, substance abuse, and unemployment.

There was also the 1948 Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act, which paid for property lost when the owners were forced into internment camps, and a second piece of legislation in 1988, which paid out $20,000 with an apology to each direct survivor. Exactly what good was done by these gestures remains open to discussion. It certainly has not stopped George Take from making a post-Star Trek career as a professional victim.

There’s nothing wrong with moral gestures per se, but when you’re opening the public purse to assign a dollar value to righteousness, it’s reasonable to ask what the money buys. Does racism end in America? Do angry whites quit hating blacks? Do people bartering victimhood into entitlement quit? If we accept black leaders‘ judgment that there is an ongoing de jure and de facto impact of slavery today, do those also go away? Or do we just drift back into “conversations” about race, having spent money in search of a solution it ultimately can’t provide? The cynicism that accompanies such conclusions is only part of the problem, however. Worse is how reparations are a damaging distraction.

Talk about reparations that have no chance of happening is an excuse to avoid the much harder work of enforcing our anti-discrimination laws in employment and housing, making sure schools are not separate and unequal, and lifting millions of Americans of all races out of poverty. Those challenges will not go away with reparations.

America is complicated, as it is not just a black/white society, less so every year. So politically, how do Latinos feel if there’s a big investment just in the African-American community, and they’re looking around and saying, “We’re poor as well. What kind of help are we getting?”

Before you decide I’m a racist, that last paragraph isn’t my words. It’s what Barack Obama had to say about reparations. He wasn’t invited to the latest hearings, and his thoughts are very much missing from the dialogue today.

Peter Van Buren, a 24-year State Department veteran, is the author of We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People and Hooper’s War: A Novel of WWII Japan.