Making the World Safe for Oligopoly

On December 21, 2000, in the closing hours of the 106th Congress, the Commodities Futures Modernization Act, complete with a lethal provision absolving certain toxic financial derivatives from regulation, glided quietly through the Senate, and was duly signed into law without demur by President Bill Clinton. For years, like the shark in Jaws, it moved beneath the surface, invisible to a heedless public. Then, in 2008, it erupted terrifyingly into the sunlight, as the world watched the global financial fabric ripped to shreds by the immensely destructive derivatives it had been protecting. In many ways, we are still recovering from that disaster.

Despite the destructive effects they can inflict on the rest of us, financial legislation, rules, and regulations all too often lurk amid thickets of small print, unnoticed by the world at large. This is neither surprising nor coincidental, given the generally incomprehensible language in which they are written. Who but a securities lawyer or bank lobbyist would have known, for example, the real meaning and purpose of footnote 563 of the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission’s implementing rules for the 2011 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act?

Dodd-Frank, among other things, was supposed to curb the worst excesses of derivatives trading as enabled by the earlier act. But footnote 563 (out of 662) to the rules reads: “Requirements should not apply if a non-U.S. swap dealer or non-U.S. MSP [the counterparty, or person on the other side of a trade] relies on a written representation by a non-U.S. counterpart that its obligations under the swap are not guaranteed with recourse by a U.S. person.”

These seemingly innocuous words comprehensively vaporized the entire much-heralded reform of the $700 trillion derivative market that had so nearly blown up the world just a few years earlier. The coded language signaled that trades run through an overseas subsidiary designated “non-guaranteed” by a parent corporation were entirely exempt from the regulations. Almost immediately, the bulk of U.S. derivatives trades began flowing through London-based subsidiaries, thereby evading the purpose of the Act.

While enacting this hollow reform of the derivatives market, Dodd-Frank also alleged to address the more fundamental problem of “too big to fail.” In 2008, the threat of monster institutions such as Citigroup and the AIG insurance company collapsing and bringing down the financial system had prompted panic and bailouts from the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve that ultimately amounted to some $16 trillion. Not surprisingly, giving this largesse to the very people who had cratered the system enraged the public, sparking the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements. Politicians therefore deemed it expedient to claim that the problem would not recur.

“No more bailouts,” crowed then-senator Chris Dodd. “Not only politically could you not get away with what we were able to do in 2008,” but, thanks to his eponymous legislation, “legally you cannot do it.”

However, to quote the poet Robert Burns, the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry, especially if there are platoons of well-remunerated lawyers and lobbyists helping the process along. In this case, the end result would appear to be that not only can our native Wall Street behemoths rest easy in the assurance that they will not be allowed to fail, their fellow “systemically important” banks around the globe now enjoy similar privileges.

Here’s how it worked: to ensure that the chaotic scramble of the 2008 bailouts would not be repeated, Title II of the new law created an “Orderly Liquidation Authority.” It stipulated that in the event that some “systemically important” financial institution appeared to be expiring, the secretary of the Treasury, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, and the president of the United States were to gather in private and agree to wind down the imperiled entity in an orderly and decorous manner, a process that would be carried out by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. This process, involving the highest levels of government, bears no resemblance to the process by which almost any other American company would be dissolved for foolhardy business practices. If Boeing, Microsoft, or some other large non-financial corporation should find itself in similarly dire straits, the only recourse is the bankruptcy court, with a judge overseeing the auctioning off of company assets in settlement of its debts and each creditor bound to stand in line for its meager portion. There would be recourse to the unbounded largesse of a federal regulator such as the FDIC.

The FDIC was created in the depths of the Great Depression in order to safeguard bank creditors, i.e. depositors like you and me, by taking control of an insolvent bank, reassuring depositors with a taxpayer-backed guarantee—and merging it with a solvent bank. But the “systemically important financial institutions” (SIFIs) that the new law rendered eligible for FDIC protections, such as JP Morgan or Citigroup, are not banks in the traditional sense, but financial holding corporations that may or may not own one or more banks. So what the law actually does is to offer “customers,” meaning counter-parties on the other side of “qualified financial contracts” (such as derivatives, securities loans, commodity contracts, futures deals, etc.) the same taxpayer-backed protection as ordinary bank depositors.

A securities lawyer well versed in the subtleties of the arrangement put it to me this way: “It’s all been based on the theory that, ‘oh, we’re limiting systemic risk, and we’re going to make sure we never have to do one of these emergency bailouts again,’ which is probably true, but it’s only true because they’ve already baked in the bailout…we now have this very clear implicit assumption that ‘there’s no possible way JP Morgan is going to be allowed to fail. So, go ahead and continue to do business with them.’”

Following the creation of “orderly liquidation” as a solution to the too big to fail problem in the U.S, other countries hosting important financial centers, still traumatized by the near-catastrophe of 2008, followed suit and set up their own liquidation procedures. But there remained a potential fly in the ointment: anyone doing business with a U.S. TBTF corporation could relax in the assurance that their money was safe. But what about cross-border deals with foreign corporations? Suppose, for example, a farmer in Iowa entered into a contract with a non-bank subsidiary of a Swiss mega-bank (call it “Swiss-U.S. swap company”) to hedge the price risk on his corn and put up collateral to seal the deal. Should it come to pass that the mega-bank back in Zurich went broke, the farmer would naturally seek to cancel the contract and take back the collateral. The farmer’s right to do so is protected under the U.S. bankruptcy code, thanks to an amendment to that law passed by Congress in 1990, ironically in the name of protecting against “systemic risk.”

But while this outcome would be good for the farmer it would be highly inconvenient for the Swiss authorities, who would be seeking to hoover up all the assets of the mega-bank in order to subject it to an “orderly resolution.”

Happily, at least for the international corporate universe, such irksome disturbances have been precluded by an unpublicized but potent agreement—not between governments, but by an international organization of which few outside the rarefied world of high finance have ever heard. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), with the motto “Safe, Efficient Markets,” is the trade organization for the multi-trillion dollar derivatives industry. It not only regulates the business, but keeps a watchful eye on the official state-sponsored regulators to make sure that meddlesome officials put in place no unwelcome restrictions. On July 31, 2018, ISDA issued what it termed a Resolution Stay Protocol “to enable parties to Protocol Covered Agreements…to amend the terms of each such Protocol Covered Agreement to contractually recognize the cross-border application of special resolution regimes applicable to certain financial companies and support the resolution of certain financial companies under the United States Bankruptcy Code.”

What this meant in English was that customers like our farmer who discovered that their counter-party in a deal was going broke were bound not to try and declare them bankrupt so they could grab some of their money back. They had to leave them to the orderly liquidation of their home governments which, as we have seen, had issued the implicit guarantee that they were too big to fail. Dutifully, global regulators, including in the U.S., required that TBTF firms demand that their counter-parties sign the Protocol and waive their rights to escape contracts with seemingly doomed subsidiaries.

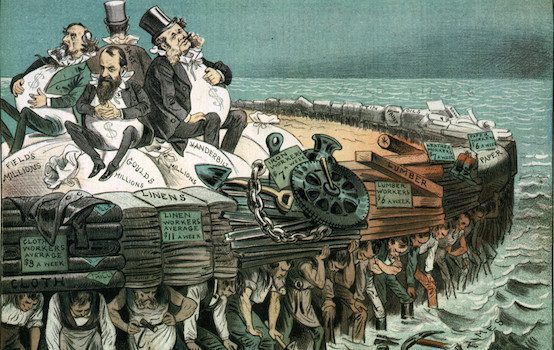

Beneath all the mind-numbing legalese, therefore, lurks a very significant message: too big to fail has been cemented in place everywhere, ensuring that the global financial system is absolutely dominated by a limited number of giant financial holding companies—not all of them banks. Secure in their governments’ protection, they enjoy privileges that protect them against competition, such as the cheap money that comes with a sky-high credit rating by virtue of their taxpayer-backed guarantee against failure. Customers have little choice but to use these firms, and little reason to object, knowing that governments around the globe will stand behind their “national champion” financial firms. Their senior managers and CEOs can therefore relax in the assurance that they are doing “God’s work” as they enjoy their stratospheric annual compensation.

We will not know how well this cozy system to make the world safe for oligopoly will work until the next financial crisis breaks around us. Such events are inevitable, and have been so since at least the year A.D. 33, when the over-leveraged Roman banking system teetered on the brink of collapse. It was rescued, of course, by an imperial bailout.

Andrew Cockburn is the Washington editor of Harper’s Magazine and the author of five nonfiction books, including Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins (2016). He has written for The New York Times, The New Yorker, Playboy, Vanity Fair, and National Geographic, among other publications. He currently lives in Washington, D.C.

Comments