Daniel R. DePetris is a foreign policy analyst, a columnist at Reuters, and a frequent contributor to The American Conservative.

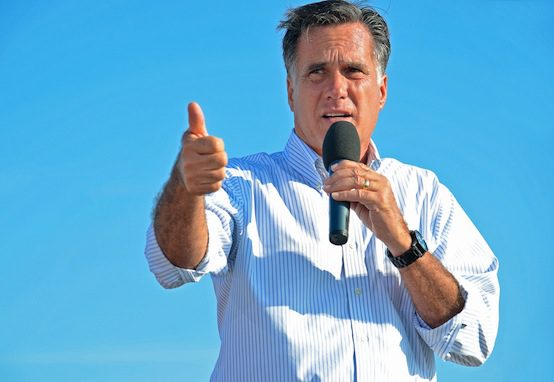

America Falls Out of Love With Mitt Romney’s Foreign Policy

When Mitt Romney lost to Barack Obama in a presidential election that most Republicans believed was winnable, the former Massachusetts governor was quickly dismissed as an also-ran—the GOP version of Michael Dukakis. He was no longer the handsome, older, savvy businessman who would turn the economy around, but a bumbling, privileged stiff who couldn’t dislodge a vulnerable incumbent.

The stink of the 2012 defeat stuck to Romney during the 2016 GOP presidential primary, when then-candidate Donald Trump excoriated him for choking like a dog.

The tables have now turned slightly. Many Republicans now look at Romney not as a defeated nominee, but as a statesman of sorts. No doubt Never Trumpers like Bill Kristol and Rick Wilson are praying that Romney challenges the president in 2020 and brings the Republican Party back to the time when Trump was just another reality television star.

Romney, of course, already decided that a third presidential run wasn’t worth it. Being a U.S. senator, however, was another story. So he ran for a seat in Utah and won overwhelmingly in 2018. Six months later, there he was on the Senate floor, giving his maiden address, subtly poking Trump in the ribs without saying his name.

He talked about everything you would expect him to talk about: morality, civility, decency, freedom, unity, free trade…and alliances.

One of the major gripes from Democrats and many Republicans in Washington is that Trump doesn’t care much for alliances. He treats friends like foes and foes like friends. This is a slogan tailor-made for a bumper sticker, but it’s also what a significant swath of the establishment believes.

Trump may deliver a speech in London and mouth nice words about the “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom, but deep down he looks at everything as a transaction. He isn’t the first commander-in-chief to fulminate in private about the stingy Europeans who don’t provide their citizens with national defense capabilities befitting a Western power. But he is the first to openly, strongly, and repeatedly condemn them for it.

The 45th president views trade predominantly as a balance sheet. South Korea, Mexico, Japan, the European Union—it doesn’t matter how long a country has been a friend to the United States. If the U.S. is running a trade deficit, then it must get tougher and demand fairer terms.

The Washington establishment can’t stand this approach. The president’s critics and even some of his supporters regard it as overly simplistic, deliberately antagonistic, and plain rude. Romney is one of those people, and he said it outright on the Senate floor on June 4.

“It is in the United States’ most vital interest to see a strong NATO, a strong Europe, stronger ties with the free nations of Asia and the subcontinent, and with every free country,” the junior senator from Utah remarked. “We need to hold our friends closer, not neglect them or drive them away.”

Therein lies the Republican foreign policy dichotomy today. On one side are the Romneys, Marco Rubios, and Bret Stephenses of the world who continue to peddle stereotypical phrases like “U.S.-led liberal international order,” and label any finger-wagging at U.S. allies as disrespectful, childish, and ultimately counterproductive. And then you have Trump, a far more nationalist figure who thinks the U.S. is being exploited by countries that should be thanking us for our help.

Both sides have their faults. Trump’s worldview is steeped in his decades-long career in real estate, marketing, and show business—industries that prize the bottom lines of profit and ratings. This is reflected in his admiration for Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a walking, talking diplomatic disaster if there ever was one. But outwardly, Salman exudes power and decisiveness—and is more than happy to purchase tens of billions of dollars in U.S. military weapon systems with which to bomb his enemies.

Both sides, though, are also right in part. Mitt Romney correctly underscores that America’s alliance system is one of our nation’s greatest strengths. But Donald Trump is right that maintaining alliances for their own sake—and without expecting anything tangible in return—shouldn’t be the objective, and may in fact perpetuate an unsustainable status quo.

There are few Republicans who have truly sought a happy medium between the Romney and Trump approaches on foreign policy. Most foreign policy on Capitol Hill is reflexive, hewing to shopworn internationalist talking points or hawkish posturing. In terms of what the American people want, however, Trump’s preference for a greater degree of restraint and putting democracy promotion and regime change in the rear-view mirror appears to be winning out.

In the words of a February 2019 Eurasia Group Foundation report authored by New York University’s Mark Hannah, the “desire for a more focused foreign policy is at odds with the more expansive role generally favored by foreign policy experts.” The liberal hegemony Mitt Romney continues to preach like gospel on the Senate floor is fast becoming unpopular among the broader electorate.

It is clear now that there has never been a period in the modern era when the establishment Mitt Romney represents has lost so much of its appeal. It will be interesting to see whether Republican lawmakers, elected to represent their constituencies at home, begin to fall in line with the rest of America.

Comments