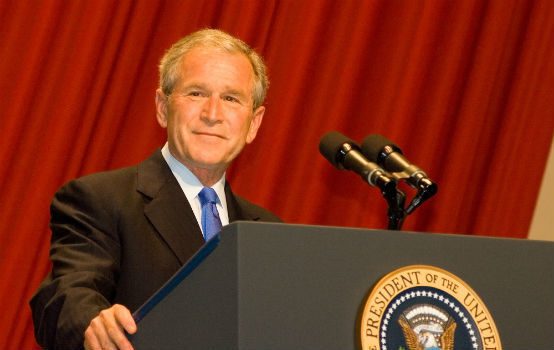

A Tax Cut Straight from the George W. Bush Playbook

As the Senate celebrates passage of its $1.5 trillion tax cut package, Republicans still have a daunting task ahead of them. They’ll have to iron out some significant inconsistencies between the Senate and House bills, as well as settle on what can realistically be achieved. They’ll also have to figure out how to sell what could be their only legislative achievement of 2017 without it succumbing to the usual cries of “tax cuts for the rich!”

Earlier this year, Republicans claimed that tax reform would simplify the tax code. One look at the bill the House rolled out proves this is not true. The GOP legislation accepts the premise of taxing wealthier people more and retains—and actually adds—layers of tax brackets. It does eliminate several popular deductions, which could be seen as a simplification—unless you’re one of the people benefitting from them.

On balance, a tax cut would help grow the economy. The U.S. has the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world at 39.1 percent, so any bill that lowers that number will help boost employment.

But this is also a deficit-financed tax cut—in other words, we’re putting the $1.5 trillion on credit, which we’ll have to pay back over the next 10 years. And that $1.5 trillion tab is a conservative estimate, as the bill actually provides $3 trillion in cuts by sunsetting certain provisions. Republicans are asserting that the cut to the corporate rate will bolster the economy so dramatically that the package will pay for itself. But there are serious reasons lawmakers should be wary of this argument.

First, it was taken directly from the George W. Bush-era tax cut playbook. It seems like ages ago that the government actually had a surplus, but back when it did, President Bush argued that his tax cuts would be paid for with increased revenue from a boosted economy. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan agreed, citing the government’s projected surpluses. But that was before the housing market bubble and the Wall Street crash, which caused revenue projections to fall dramatically. Ultimately, the Bush tax cuts were paid for on credit. And that’s a problem because tax bills that are paid for have positive effects on the economy, whereas deficit-financed tax cuts have very little to negative long-term impact on growth.

Secondly, more than two thirds of the nation’s debt comes directly from autopilot spending programs. When lawmakers discuss “cuts,” they’re only talking about discretionary spending—less than a third of overall spending. With an insolvent Social Security trust fund, Congress needs to get serious about the nation’s long-term fiscal health and slash the spending side of the equation. It’s simply magical thinking to believe that our financial problems can be solved by deficit-financed tax cuts alone.

Finally, we need to actually retire debt during times of economic growth, so that if and when the market crashes, we are not drowning in red ink. Interest rates will eventually rise, and somewhere down the road, the global economy may suffer another burst bubble. It’s massively shortsighted to face that future day with over $1 trillion in debt from this tax cut alone.

As the wrinkles in the bill are ironed out in conference committee, some of these issues may be resolved. But the debt problem likely won’t be. Senator Bob Corker attempted to secure a legislative trigger that would have repealed the tax cuts if they caused deficits—but that provision was ultimately left out and Corker voted against the Senate package.

There are significant differences between the House and Senate versions that need to be resolved, including whether individual tax cuts should be permanent, whether to repeal the health insurance mandate, when to enact a corporate tax cut, and how to handle the mortgage interest and state and local tax deductions.

Other provisions are consistent across both bills. Senate lawmakers decided to include a section of the House bill that repeals the Johnson amendment, an unnecessary and unfair penalization of political speech that takes place in churches, religious schools, and other tax-exempt non-profits.

As conference legislation starts to take shape, the question before conservatives is whether its inevitable shortcomings are significant enough to cost their support. Senator Rand Paul, an ardent fiscal conservative, argues that lawmakers should not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Paul wrote in an op-ed:

I would prefer a larger cut. I would prefer that the Senate bill match the House bill and keep some form of state and local deductions so that no one gets caught in the trap of losing too many deductions at once and failing to benefit from the tax cuts. Lastly, I’d like to see more permanence on the individual side. Some of that is still achievable. Some of it is due to the peculiarities of the budget and Senate rules and will have to wait for another day. The good news is—we can do this every year.

It’s true that the bill could—and should—be better. Having to vote for the least-bad option is one of the most frustrating parts of our current politics. The cut to the corporate tax rate will undoubtedly bolster the labor market and add U.S. jobs, which are significant positives. But lawmakers also need to ask themselves whether that’s worth adding $1.5 trillion to our debt—and whether our heedless and headlong national spending spree will ever come to an end.

Barbara Boland is the former weekend editor of the Washington Examiner. Her work has been featured on Fox News, the Drudge Report, HotAir.com, RealClearDefense, RealClearPolitics, and elsewhere. She’s the author of Patton Uncovered, a book about General Patton in World War II, and is a summa cum laude graduate of Immaculata University. Follow her on Twitter @BBatDC.

Comments