American Orphans in the Wasteland

On this Memorial Day, we hope you’ll appreciate revisiting this feature from our January/February issue.

We strode through the rubble of West Raqqa, a section of the city recently wrested from ISIS that July of 2017. Rifle shots echoed through the streets. The shots were not, I thought, directed at us, half a dozen Americans, Syriac Christians, and Kurds, but we moved nonetheless toward the exchange of fire, toward a building held by Kurds from Qamishli, the frontline against ISIS. To reach it, we would have to sprint over an open area of street perhaps a hundred yards across. Before we got there, I slowed to take a photo. An American fighting with a Christian militia saw me slow and yelled, “It’s usually the last guy who gets hit.”

As we reached the street, I caught up to the others and we sprinted to the building, closer to ISIS yet somehow safer. We climbed the stairs toward the roof, part of which had been blown open by explosions days before, and from there watched the sunset amid sniper exchanges that grew infrequent in the gathering night. The young men interlocked arms at the shoulder and smiled for photos, delighted in one another’s company, delighted to cheat death another day.

It seemed that every man-made thing in Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and the Euphrates—the cradle of civilization—was a wasteland. Only the desert lay untouched. By its barren roads one came to Raqqa, the heart of what remained of the Islamic State, a site of torture, crucifixions, and worse. Raqqa had been a desert frontier city in antiquity; then a crossroads of Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Persian empires; then the capital of the Caliph Harun al-Rushid, and lately of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. That caliphate was slowly losing ground in bloody assaults by a makeshift army of unbelievers.

The place was emptied of most life, the pale buildings but skeletal remains of a city. Aside from some trapped civilians and ISIS hostages, those who remained were the Arab, Kurdish, and foreign soldiers of the Syrian Democratic Forces on the one side and the equally diverse forces of the Islamic State on the other. This was a country governed by no state and no order any westerner could comprehend, yet it was a frontier between good and evil. Here, also, were two Americans.

Nearly two years later, on May 2, 2019, I sat at my desk in Washington, D.C., and found in my email a picture in which that American, Kevin Howard, looked back to warn me not to stop lest I be hit by a sniper. His eyes were sunken and aloof, the obscured windows of a wounded soul. In the foreground was another American, Taylor “Doc” Hudson, who ran point, crouching down as he approached the open crossing. Kevin was 29 at the time, a former Marine who grew up in the foster care system in California, enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17, and served in Iraq. Doc was a soldier-medic in the SDF, also from California. Both Kevin and Doc saw reports of the horrors ISIS was inflicting on Yazidi women and children—rape, enslavement, mutilation, murder—and decided that this was their fight. “I couldn’t sleep after I saw what was happening to the Yazidis,” Doc told me in Raqqa.

They did not know each other in 2014 when ISIS conquered much of Mesopotamia, but their lives soon became bound up in war, a premodern war fought by soldiers from the four corners of the earth, tribesmen, conscripts, teenage orphans, ideologues and idealists, devout believers and sociopaths.

Each participant had a name—often several—to distinguish his war self from his other self. Kevin had been called “Kane” in the French Foreign Legion, “Zagros” by the Kurds of the YPG, and “Christian” in his new unit, the Syriac Military Council (MFS). That unit began with a handful of Christians but now included Muslims, both Arab and Kurd, and other ethnic and religious minorities. Taylor was known variously as “Paul” in the Foreign Legion, “Akkad” after the son of an Assyrian family who was killed when ISIS overran the Khabur river region in 2015, and “Doc,” as he prefers to be called by those who knew him in Syria.

Soldiers on all sides assumed noms de guerre, usually linked to their places of origin. Kevin and Doc’s war names were not, but neither was that place altogether irrelevant, at least in my mind. In travels around the region, Americans from the West coast, especially California, seemed to turn up in the most unexpected places. There was the tall, young Arab man in traditional attire who approached me in Sa’ana, Yemen, to ask in unaccented American English where I was from. He was from California. Then there was the American who had joined ISIS and worked in their Mosul headquarters, then disappeared as the fighting intensified in 2016; he too was from California. There were others. Why did they always seem to be from the western edge of the continent?

Frederick Jackson Turner argued that it was the frontier that formed America’s institutions and the egalitarian mindset of those who conquered it. California was the place where the American frontier ended and the Pacific began. The errand into the continent’s vast wilderness of forests, deserts, and mountains began in the backcountry of Appalachia and spanned the continent to the Pacific. It was there, amid cruel nature and primitive violence, that the American sense of liberty took form, that second sons forged new destinies or perished, that fallen men were made anew. The American frontier not only shaped the character of its citizens but captured the imagination of people around the world.

The American West was a place where bastards and orphans might be redeemed, where good and evil flourished at extremes and in close proximity. The settling of California may have marked the end of the frontier, but not of its underlying spirit—the wanderlust, adventurism, and idealism.

By the time Kevin and Doc were born, there was little in California to test one’s mettle. It was by then synonymous with extravagance, comfort, and perhaps, above all, vanity. But they decided to pursue the ancient test of manhood—war—and to do so against the unequivocal evil of their day. It’s not so easy to distinguish or even perceive good and evil amid the bourgeois comfort and postmodern values of contemporary America. The fight against ISIS offered precisely that stark dichotomy. In that fight, they were prepared to stake all.

***

And so the two sons of California made their way to the deserts of Mesopotamia, compelled by idealism, brokenness, adventure, redemption, madness—any and all of the above. They traded in the comforts of the domesticated frontier for the austerity of the desert, for millennia a place of purification and preparation, a liminal space between the before and after, where one shed his identity and assumed another. Or a place to confront temptation and evil. It was also a place for healing. Even the soldier might find in the desert that which in every generation draws prophets and monks: clarity of mind and spirit. It was the same for Kevin and Doc, and for those whom they fought beside and against, whose ancestors had also gone into the desert to find meaning, though they spoke different languages and professed different creeds.

They were better prepared than many who fought there. Kevin had served in combat with the Marine Corps in Iraq, where he was wounded, and had some sense of what to expect. SDF units were ethno-linguistically and ideologically diverse and this inhibited communication and coordination. They were also less well-equipped than the U.S. military. But Kevin was used to hardship from childhood. He told me in Raqqa that he was an orphan, that much of his youth was spent in a boys home. There was an intensity with which he conveyed the name: “The Hanna Boys Center.” He paused and pointed at the notebook as I wrote, a deliberate gesture that I pondered later. When he came of age, he served in the Marine Corps and, after a brief incarceration, the Foreign Legion.

Doc had little military training besides familiarity with weapons. His primary role in the SDF was as a medic, since he had some medical training. He also had joined the Foreign Legion but like Kevin did not stay long. His own upbringing was more stable than Kevin’s: two parents whom he knew and an education at private schools. The two met in Syria in 2016 and fought in several battles together against ISIS.

One of the largest militia groups in the SDF was the YPG, a secular Marxist offshoot comprised heavily of progressive-minded Kurds. Kevin and Doc were quickly disillusioned with the YPG. “If you can get people to die for atheism, you have a frightening ideology,” Doc told me in 2017. They left the YPG for the MFS, a smaller but growing unit within the U.S.-backed SDF. The Syriac unit imposed no ideology and as a result attracted diverse recruits. But the YPG Kurds were consummate fighters and Kevin and Doc admired them, especially the fearlessness with which they fought. The dark mystique of ISIS struck terror in hearts from Mesopotamia to North America. But these Kurds, like many Syriac soldiers, were unafraid of ISIS or death, and there was a freedom in that. Still, the MFS remained their unit, perhaps because there is more even to war than fighting.

By the time I met them in 2017, Kevin and Doc were masters of their craft. They had survived the Battle of Tabqa Dam months earlier and were now in West Raqqa, where the SDF had participated in brutal urban combat earlier that summer. After weeks of relative calm, there was a skirmish one morning after an ISIS suicide bomber attacked an SDF position, followed by intense exchanges of fire and larger ordnance. Kevin spoke afterward of the “fog” that takes over, in which the context of the moment fades and the combatant goes on autopilot. It is a common feature of war that science has only recently begun to understand. In these moments, the amygdala, sensing danger, commands the hypothalamus to release adrenaline—the “fight or flight hormone”—into the bloodstream. A kind of rush ensues. The long-term effects on the brain and nervous system are harmful, but in the instant moment it fuels a kind of euphoria. All of this occurs in split seconds, without conscious direction.

“At our first major battle in Raqqa, we fought for 30 hours straight,” says Doc. “When it’s over, your body aches and you crash. But at the time, you don’t really notice.” Humans are not designed for such protracted conditions. As with drugs, a person can become addicted to the exhilaration of the adrenaline rush. Also as with drugs, the crash that inevitably follows is often accompanied by a sense of shame, complicated by the presence of euphoria and trauma from the violence witnessed or inflicted. Many who survive violent trauma only find consolation in the company of others who’ve endured similar experiences; words invariably prove inadequate, but the sense of sharedness can alleviate the shame and loneliness. Afterward, many try to recapture that euphoria in drugs or alcohol or some other experience. In the process, they become isolated from family and friends, exiles within themselves, never again quite free but instead slaves to an experience in the past that they try to relive or redeem.

That intensity and burnout was already present in the eyes of the combatants of Raqqa. I wondered about ISIS, a few hundred yards away. Here were young men with anima, with life and spirit. Every branch of Abraham’s descendants was here fighting under some banner or other, exiles from their countries, even a few from America.

In Nineveh, in neighboring Iraq, I had seen where ISIS slept on stone floors in churches and tunneled deep into the earth to survive airstrikes. They destroyed tombstones and used statues of Christ and his mother for target practice. They strapped explosives to themselves and charged forth like the Gadarene herd, as if possessed by some primitive region of the mind where blood lust and libido dominandi reigned. “Creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present,” Orwell wrote of the Nazis, “and if they are ghosts they are at any rate ghosts which need a strong magic to lay them.” Creatures. Ghosts. That strong magic consisted of a blend of airstrikes and people like Kevin and Doc. In this war they flourished, lords of a stateless chaos.

This was not a war whose gentlemen victors and vanquished would later hold reunions at renowned battlefields or whose “no man’s land” would be crossed for a Christmas truce. In this war, no limits were set by standards of chivalry, nor did emissaries bear gifts for each camp’s king. Such pleasantries occurred even during the Crusades, but not here. This was total war, waged by drug-riddled jihadists, who weaponized drones and burrowed into the earth with shovels and desecrated cemeteries, an ancient pagan ritual in which the conqueror eradicates all memory of the ancestors of the vanquished—any trace that Yazidis and Christians ever dwelt there.

ISIS maximized the terror they inflicted on captives and adversaries. As the SDF closed on a hospital in Raqqa, ISIS held children up in windows in the hopes that the SDF might shoot at the movement, not able to discern the children at that distance. Around this time, the SDF learned that ISIS was welding families into buildings, concrete tombs above ground where the poor civilians were left to die of thirst or hunger or airstrikes. This revelation slowed the advance of the SDF, which sought to avoid civilian casualties. “You didn’t kick doors, because they’re booby trapped,” Doc recalled. “So we blew walls down with satchel charges. Some guys killed families who were welded in. It was incredibly savage. Those people are subhuman. All so that ISIS could report back that we were killing civilians for propaganda.” Despite this and similar tactics, the death toll of civilians was relatively low; the casualty rates among some SDF units, however, were staggeringly high. All of it was more than the mind can endure for long. Kevin and Doc had already endured it for more than a year.

About a month after we met in 2017, an ISIS drone-mortar hit their position in Raqqa. Doc suffered a traumatic brain injury and was hospitalized for several months. The ensuing blurred vision, dizziness, and a lack of depth perception made it impossible either to fight or serve as a medic. As Doc healed and Kevin increasingly showed the effects of exhaustion, compounded by his own traumatic brain injury from combat in the Marines, they began to question what they were doing there. All that once seemed clear was increasingly obscure. I’d told them at our parting, “You have to go home, and when you get there, you have to heal. You’ve done your part in this fight.” They didn’t agree or disagree; they seemed like brawlers who would welcome restraint from others but wouldn’t walk away voluntarily. It may be that they feared going home more than staying, that that which made them cling to this place was precisely what was destroying them. In the chaos and violence of this wasteland they at least had a telos.

But what awaited them at home? The former frontier was a land of strip malls and suburban plenty—an air-conditioned world designed to insulate persons from any discomfort and reality, however ugly. The identities Kevin and Doc had forged in Syria might dissipate in America, where they would be reabsorbed without differentiation. It seemed a choice between two wastelands. Part of them felt more at home in the desert frontier. But it wasn’t really home. Nor was home. Nevertheless, they decided to make their way back, through months of setbacks, negotiations, and border crossings, all during a war in Syria and a Kurdish push for independence in Iraq. They finally arrived, after a long journey, in America.

***

The first time Kevin Howard returned home, after his discharge from the Marine Corps, he went to a party where he saw his girlfriend with another man. Enraged, he drew a handgun, threatened the man, fired shots into the ceiling, and was subsequently arrested and served time. Infidelity haunts the imagination of the soldier far from home, so much so that an oral tradition of “Jody calls” has been around since at least World War II. (“Jody” is the dishonorable fellow back home who pursues the soldier’s girlfriend in his absence.) Generations of drill sergeants have used Jody cadences to dampen the homesickness or depression of trainees, to inure them to betrayal. Kevin’s girlfriend had been his first, but not his last experience of betrayal.

After they parted ways in the Middle East, Kevin and Doc didn’t see each other again until the summer of 2018. Doc returned to Tucson, Kevin to the Bay Area, where he’d grown up. Kevin was nearly penniless when he got back from Syria and soon left the Bay Area for Montana and then the Dakotas to work in the oil fields. He worked the fire season in Oregon before returning once more to the Bay Area, where he tried to get housing from Veterans Affairs. When he was informed that the wait would be six months, Kevin landed on the streets. He called Doc, who sent him what money he had (a few hundred dollars) and told him to come to Tucson. Kevin came and Doc found space for him.

Kevin carried with him a list of things he wanted to do in his life, one of which was to own a house. To share in Doc’s house in Tucson meant a great deal to him. Kevin also found a girlfriend and for a time seemed to believe that assimilation into civilian life might be possible, even imperative. But there was another part of him that longed for what they had left behind. The frontier wilderness beckoned, with its war and chaos, its terrible euphoria and moral clarity and purpose. Kevin had wounds from the Middle East but also from childhood, untreated through his life, unhealed by the years.

Around the time Kevin was making his way back from Syria, news stories began to break in California about sexual abuse at the Hanna Boys Center. The abuse took place over a period of fourteen years, which overlapped with Kevin’s time there. Kevin seethed with anger when the center came up; Doc suspected that he had suffered abuse there, or perhaps earlier in life.

The return to America was hard for Doc, too. His place in Tucson was in the flight path of the local Air Force base, and when planes flew over in the night (especially the A-10), he lay in bed and shook. He often remained in his room in the first months back. “There would be days without any sleep and then I’d sleep 20 hours straight,” he recalled. Doc weighed the idea of using land bequeathed to him to start a desert retreat for combat veterans. Kevin, ever prone to swings, urged Doc to make it a place to train for military deployments of the kind they’d joined in Syria. Doc had no interest in this. Syria was peculiar because of the evil nature of the Islamic State and the anarchic context of the war. Kevin resented the rebuff.

In the spring of 2019, Kevin came to believe that he may have been dispossessed of money owed to him by a relative. Those around him sensed that something was wrong with him. “That’s when he started talking about Myanmar,” said Doc. There was a conflict in Myanmar and Kevin considered going there to join a militia—another adventure. Doc discouraged him, noting that it was a very different war than the one in Syria. Kevin barely left his room in the week that followed. “It was easy for him to feel betrayed,” Doc reflects.

Then came the blow upon a bruise. Kevin suspected that his girlfriend had been unfaithful. For the second time, he’d fallen in love, and for the second time, he’d been betrayed. He told a Marine friend with whom he’d served in Iraq that he was contemplating suicide.

In the early evening of April 30, 2019, Kevin went into the mountains just west of Tucson, to a place on Tumamoc Hill. He took a shotgun with him. Tumamoc was adjacent to Sentinel Peak. He ascended by a circuitous path over igneous rocks and found a stone alcove on the hill’s face from which he could peer down into Tucson on the broad valley plain below. There he erected a wall of loose rocks from the hill to conceal himself.

On these hills, Spanish sentinels stood watch centuries before and before them Native Americans, the lookouts of ancient peoples whose names and histories are long since lost. Perhaps the view reminded him of the deserts of Mesopotamia, where he had defined himself against the evil of his day and fought that evil unto exhaustion. Or perhaps the view reminded him of California, of the childhood he never had and the absence of which he never mourned. In the valley below was the civilization he fought to protect, a world that had already forgotten ISIS. Beyond the city were mountains and desert, much like the place where he found, for a time, identity and meaning. Some remnant of that desert lay trapped beneath the highways, office parks, and concrete lots. Whatever his own part in the war against the ISIS caliphate, waged in another desert now far away, that fight was over. And here was desert all around but no more frontier, and no place for him in the civilization below. He had no hope of healing nor of belonging anywhere. He posted his intentions along with a photo of his view on social media.

In Oregon, Kevin’s former Marine gunnery sergeant saw his post. As Tucson police scrambled to figure out where Kevin was and determine whether the armed veteran was a threat to more than himself, the gunnery sergeant cross-referenced the image Kevin posted to geolocate his position outside Tucson. A call went out on the internet to help a brother Marine in need.

***

Stefan Rivenbark did not know the name Kevin Howard when he rose in Tucson that last day of April. He returned home from work that evening and saw on a Marine Corps message board that another Marine in Tucson was contemplating suicide. He raced in his truck toward the hills.

Rivenbark approached the police checkpoint after sundown and was turned away at the entrance to Sentinel Peak, where Doc had already been searching for hours. Rivenbark looked at the peak opposite Sentinel. “Can I search that hill?” he asked. The officer gave her assent and Rivenbark scrambled up Tumamoc Hill. At one point, he got within thirty yards of Kevin, though he did not know it. He called out in the darkness. “Kevin Howard, this is Sergeant Stefan Rivenbark, United States Marines. Can you hear me?” Kevin did not respond. The search continued.

“I was up there,” Doc recalls. “I think he knew I was up there. I hope he knew that people who cared about him were looking for him. That he wasn’t alone.” Whatever his tortured thoughts, in the night on that hillside in the desert, Kevin Howard despaired.

Doc heard three shots, Rivenbark heard two. Doc sprinted down from Sentinel Peak and across the loose rocks and the cactus-filled gap toward Tumamoc, while Rivenbark, much closer, turned toward the shots and climbed again toward the place where he’d been before, but he was stopped by the police. As each met the police, they asked, “Did you shoot him?” They had not. Kevin’s first shot (or two) were apparently fired so that the searchers could find him.

There he lay contorted among the rocks in the darkness for two hours before they found the body of Kevin Howard: Marine, convict, Legionnaire, Syriac militiaman, American, orphan. He lived in abandonment, betrayal, trauma, and violence. He died in much the same way, but not entirely alone.

***

Neither Doc nor Rivenbark slept that night. After the shots, they were escorted down by the police and waited for nearly two hours before the police confirmed that Kevin was dead. After a few sleepless hours, they returned to Tumamoc Hill and searched for the place where Kevin died. When they finally found it, they saw where his deoxygenated blood had blackened the crimson rocks, part of his skull, part of his brain, and a pair of gloves left behind in the night by the police. As they stood there, the sun rose. Pitiless time marched on.

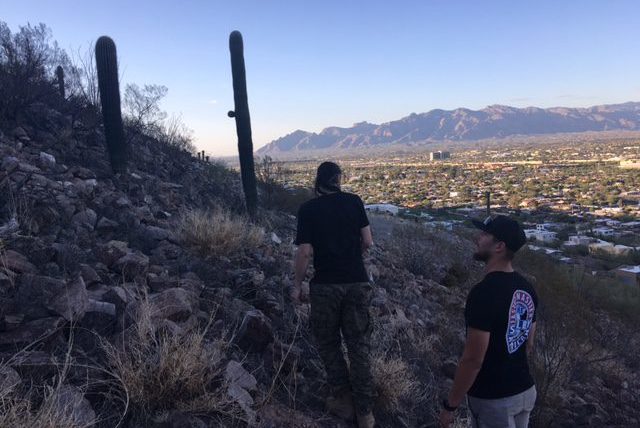

Two years later, on Memorial Day weekend 2021, I stand with Doc and Rivenbark just below Tumamoc. Rivenbark has the bearing of a Marine, tall and stoic, though this conceals the sense of duty and compassion that brought him here two years before. “I still have anxiety when I look up at this mountain,” says Rivenbark. We make our way up. It’s late in the day and the sun is setting behind Tumamoc as it did the night they searched for Kevin. It takes some time to find the spot but we eventually arrive at the stone alcove.

We stand for a long time in silence and look alternately at the ground and the valley below. The silence is broken only by brief words as the men relive that night in 2019. “I’ve thought about every scenario,” says Doc. “What if I got within a few feet, could I have stopped him then?” Minutes pass. “I thought about it for months after,” says Rivenbark. “What if I’d gotten here sooner?” We look out upon Tucson, at the fading daylight that stretches across the valley. Another lengthy silence is broken as Doc begins to weep. Rivenbark wraps an arm around him.

If Kevin had known the harm his suicide would cause, might he have gone back down the mountain? The memory of his courage on the battlefield is tarnished by this final, irrevocable act of violence, against himself, which harmed his closest friend and his brother Marines, even this stranger who searched for him in that darkness, a darkness not of his making.

When Rivenbark returned to this place after a sleepless night two years before, he saw how close he’d come to Kevin. He pondered it all again now. “I still have nightmares,” says Rivenbark. “I can smell the blood. Part of his skull on the fucking ground. The fact that they could leave that behind…” Like so many veterans, Rivenbark’s service didn’t end when he left the Marine Corps: his worst trauma came not in his part of a generation-long war in the Middle East but on a desert hill near his native Tucson. Now nightmares and fellowship bring him back to this place. It’s not the war he imagined when he enlisted, a very different kind of sentinel among the crags and cactuses.

When it is nearly dark, the three of us make our way down Tumamoc Hill.

***

“Do you remember that photograph from Raqqa,” Doc asks me at his house in Tucson, the same day we went up Tumamoc Hill. “The one with us and all the Kurds?” I tell him that I do. “You and I are the only ones alive from that picture.” He nods slowly, as if to drive home an implausible truth. “Everyone else is dead.” In the photo were Kevin and several Kurds, and a smiling Doc. A few weeks before we met in Arizona, another young American who fought with him in the SDF died of a drug overdose, by no means the first. Old comrades from the war against ISIS continue to die in the safety of America.

Doc’s house is an adobe structure whose perimeter is lined with chain-linked fence and signs that warn of dogs and security cameras. He greets me at the iron gate, gaunt and bearded, with camouflage fatigues loose on his thinned frame. He has aged far beyond the four calendar years since I met him and Kevin in Raqqa. We enter his house and sit in a cool room illumined only by light from the adjoining kitchen and cracks under the door. In the grey light, it feels like Mesopotamia long before conversation takes us back there.

“Kevin told me it’d be hard coming home,” he says. “I had no idea.” The combination of PTSD and the traumatic brain injury he suffered in Syria causes seizures and insomnia. “I’d take the worst day there over an average day here.” He pinpoints a type of trauma described by many veterans: fearlessness in the heat of battle, but terror felt far from the front when enemies struck unexpectedly. “Your expectations make all the difference. When ISIS is a few hundred meters away, you expect the worst.”

Once, while smoking cigarettes on a rooftop in Raqqa with an Arab man from the SDF, an ISIS sniper hit the Arab soldier in the head and his brains and blood splattered on Doc; a second later, the sound of the shot fired reached Doc’s ears. “It was horrific, and haunts me looking back, but it didn’t even get my heart rate up in the moment. But here when I hear a firecracker, I panic.”

The experience of terror combined with a sense of helplessness often traumatizes, setting the fight-flight-freeze response on a hair trigger in everyday life. “For me, I just function better in a war zone,” he says. “Maybe it’s because parts of my brain shut down that don’t otherwise function properly.” Neuroscience suggests this is precisely what happens.

Doc finds himself today in a third wasteland, not Mesopotamia or the American frontier but that of the traumatized mind. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, psychiatrist and leading scholar-practitioner of trauma treatment, writes in The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, “We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on the mind, brain, and body. This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present.”

The traumatic imprint thus becomes an inescapable feature of one’s psychological landscape, as much a part of the present as the rocky hills above Tucson. It also becomes the only reality in which the person feels alive. “Somehow the very event that caused them so much pain has also become their sole source of meaning,” writes van der Kolk. “They felt fully alive only when they were revisiting their traumatic past.” This is a common paradox of trauma, and the addictive rush of war: one feels trapped in a nightmare from which he seeks to escape, even while he tries to escape back into the nightmare to feel alive. The traumatized mind might even regard attempts to heal it as a threat, since to heal would be to part with the hypervigilance upon which one’s safety depends.

Trauma is not a past event for people like Kevin and Doc, nor millions of others. It resides and recurs constantly in the mind, where terrifying sensations experienced during the traumatic event replay in an endless loop. Neuroscience suggests that the traumatized brain cannot contextualize the experience by placing it safely in the past. So such people remain trapped in a nightmare from which they cannot escape and perhaps do not wish to awaken, for only in high intensity situations or in the process of re-traumatization do they feel fully present. The traumatic past thus becomes timeless, a hellish present without end.

It is a bitter irony that Kevin and Doc sought in the violent wilderness of Mesopotamia a telos that would deliver them from before into the after, only to arrive in a psychological wasteland where time halted and pain was perpetual. The relived trauma is stripped of a sense of time or forward progression. As psychiatrist and researcher Iain McGilchrist writes in The Master and His Emissary, brain damage, like trauma, can interrupt “temporal sequencing” or the “temporal flow,” which results in decontextualized fragments of experience. The sensations and intensity of the traumatic experience are relived over and over, consciously and unconsciously, amid the light of day. We are conditioned to think of Hell as a place where torments are inflicted, with the absence of time as only a secondary feature. But the cessation of time can itself be the worst affliction, akin to the absence of reason or hope. Clock time becomes the illusion, the violent experience the present reality.

The only way out of this wasteland is to restore context to the experience, to put it in the past and thus restore the temporal flow and with it context and then, perhaps, reason and meaning. This is the work of therapies like EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), a relatively new treatment that works by a process of lateralization that jars loose traumatic experiences from memory loops in order to allow the brain to contextualize them: That was Syria in 2017, but it’s in the past; I survived it and am safe here. Patients often experience EMDR as a process in which they are a passive observer; the therapist’s role is to help the patient’s brain to heal itself. Doc says EMDR helps him.

Doc knows that the wilderness he must survive, the human brain, has only begun to be mapped. It is traversed by other survivors, most of whom wander without awareness of the other sojourners. The more we learn, the better hope there is for people like Doc. He finds consolation in the other wanderers, especially military veterans. He notes that many of them also miss the intensity of a combat zone, particularly the sense of purpose that comes from fighting evil. The vets with whom he speaks, especially friends of Kevin’s, accept him as one of their own. Perhaps they understood that the war against ISIS was fought primarily not by soldiers of recognized states but by men like Kevin and Doc, soldiers of no nation. They also understand the struggle ahead will not be against evil on a battlefield but in the mind, against trauma, depression, and despair.

***

The day after his suicide in 2019, I looked at that picture of Kevin Howard from the seventh floor of the State Department and felt as far removed as one could be from the lawless roads of Mesopotamia and the polyglot militias warring on its frontiers. “It’s usually the last guy who gets hit,” he warned. It occurred to me that perhaps it had been a mistake to tell Kevin to go home. Maybe the real wasteland wasn’t the rubble of the Islamic State or the Syrian desert; maybe it was California. Maybe Kevin belonged in that strange place where he found a purpose, a telos, however alien or absurd it may seem to most of his peers, however dangerous. Maybe it was sufficient unto a life to kill evil men who raped, enslaved, and murdered. Maybe that’s more than most of us will accomplish in a lifetime.

I sat there in a prolonged silence, like the silence I would experience on Tumamoc two years later with two good men—in that place beyond words where we contemplate the chasm between what is and what ought to be, where we reason by means beyond our capacity for expression.

America ran out of frontier but not frontiersmen. The original frontiersmen sought adventure at the extremes of the New World, its chaos and violence. In the lawlessness of the Middle East, people like Kevin and Doc sought to rediscover something of that life. In the midst of chaos and violence there seemed to be a power to remake the wanderer. Kevin was a frontier orphan without roots in either blood or soil but drawn to the frontier itself. He sought the wilderness and whatever freedom or redemption he might find there—and fled deeper wounds from childhood about which we can only speculate. But the land in which he fought and bled wasn’t a destination—only one form of the wasteland in which he was trapped. The frontier was always the next, unrealized thing. Myanmar. Another war, another frontier, ever-elusive redemption and healing, permanence and meaning, a sentinel’s post in an ancient desert.

There are more Kevins than we care to imagine. Men and women who from childhood survive trauma and neglect and abuse only to remain trapped in a perpetual, hellish present. Some find themselves in the military or law enforcement or some similar role, only to discover that there is too often no place for them in the world they protect. They wander in a wilderness of sorts, not a place of preparation or purification but a lonely wasteland in which they master the craft of survival but little else. Some, like Kevin, do not survive—even as neuroscience and therapy offer healing that for a fortunate few seems miraculous.

There are more Kevins than we care to imagine. Men and women who from childhood survive trauma and neglect and abuse only to remain trapped in a perpetual, hellish present. Some find themselves in the military or law enforcement or some similar role, only to discover that there is too often no place for them in the world they protect. They wander in a wilderness of sorts, not a place of preparation or purification but a lonely wasteland in which they master the craft of survival but little else. Some, like Kevin, do not survive—even as neuroscience and therapy offer healing that for a fortunate few seems miraculous.

War and trauma and the many harsh realities of existence are familiar to our primitive selves. Everything about suburban bourgeois existence is designed to separate us from those realities. But to some that existence feels like a lie. This, at least in part, is why young men run from it, into the wilderness, into war, into alcohol and opioids. To them the lie is less tolerable than whatever may happen in the wilderness.

Christian schoolchildren are taught that God will never burden a soul with more than it can bear. As we grow older, we discover sooner or later that this, too, is a lie, likely born of the same need to take refuge from reality. Perhaps God, if he’s there at all, has a greater capacity for mercy than the cosmos has for misery.

Andrew Doran served on the Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. Department of State from 2018-21. He is a senior research fellow at the Philos Project.