A Memorable Rejection

Sometimes, American aristocrats live up to their station.

In the course of my writing career, I have become inured to rejection.

No matter the care or eagerness with which I prepare the pitch for an article, I understand that its acceptance is far from assured. Call it getting older, call it becoming jaded, but I accept that no athlete wins every game. Why should I expect that every stray idea rattling around in my head will be met with enthusiasm? I no longer find it discouraging, deflating, or even especially noteworthy to receive one of what seems to be a set of standard replies preferred by magazine and newspaper editors when declining a submission, such as “I’m going to pass” or “This doesn’t fit our needs.”

Perhaps my studied nonchalance when it comes to editorial rejection can be traced back to one of my earliest submissions for publication. At the age of 12, I sent a batch of my political cartoons to the New York office of George magazine—and the rejection I received in the mail was so memorable that I asked my parents to frame it.

Some context may be necessary: Prior to finding my true calling as a critic and opinion journalist, I fancied myself a future daily newspaper cartoonist in the tradition of Charles M. Schulz or Bill Watterson. Already bewitched by the idea of appearing regularly in print, I suspect that the serial nature of the comic-strip format appealed to me: What could be better, I reckoned, than to be guaranteed a spot in the newspaper seven days a week? Not even breaking news or late sports scores could eat into the space carved out each day for Peanuts.

Recognizing that I was, at best, several years away from newspaper syndication, I set my sights on placing my panels on an ad hoc basis in my favorite magazines, which included, at the time, George. This magazine not only appealed to my burgeoning political interests—at some point, my hero worship had switched from Schulz and Watterson to Garry Trudeau and Jules Feiffer—but had something else going for it: the Kennedy mystique.

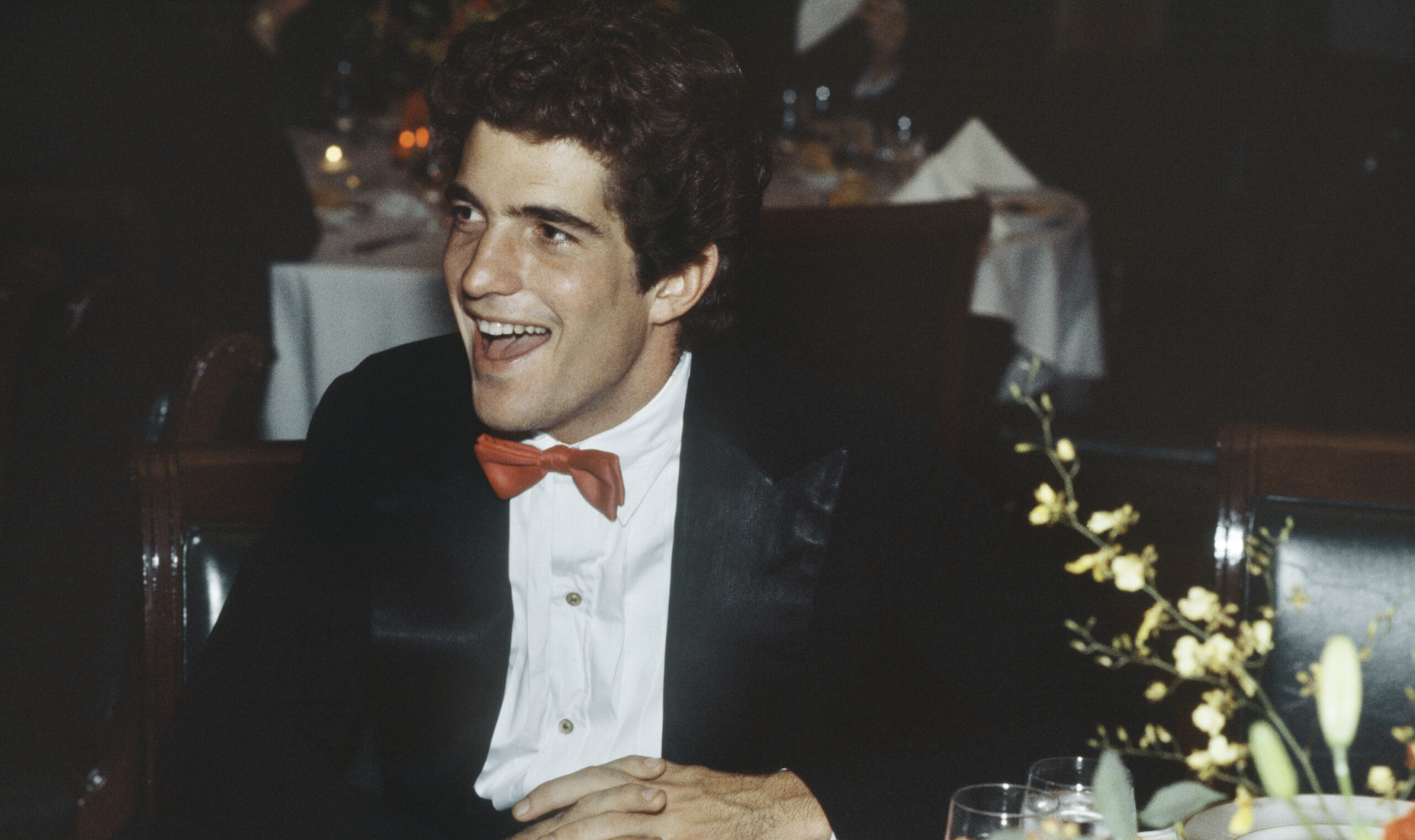

Founded in 1995, George represented a kind of mid-career do-over for the cofounder and editor John F. Kennedy, Jr. Having struck out in his sojourns as an actor and attorney, Kennedy evidently decided that Charles Foster Kane was a plausible model to emulate for his third attempt at finding a calling. What can be said except that print media still looked like a winning industry in the 1990s?

I remember George as being a fun, peppy publication with no particular political axe to grind—it was probably where I first encountered the bylines of both Norman Mailer and Ann Coulter—but I would be lying if I said that I paid attention to it for any reason other than its editor’s famous family.

In the same manner that she attended to the doings of the British royal family, my mother had been an enthusiast of the Kennedy family since the 1960 presidential election, when she, alone among her family, rooted for JFK over Nixon. Among her most treasured possessions was Six White Horses, a touching book-length poem written by a high-school student in Michigan named Candy Geer amid the national mourning following the president’s assassination. The poem, accompanied by haunting, evocative pen-and-ink illustrations, imagines JFK Jr.’s thought process as he attends his fallen father’s funeral: “They said my Daddy’s in that box— / The black one, with the six gold locks.” My mother’s younger brother gave her the book, and among all the moves she made in her life, she never lost it.

So, with the weight of my family’s reverence for the Kennedy family in the back of my mind, I submitted a batch of comic strip samples to George magazine. I have no idea what I sent, but I suspect that my cartoons parodied the political figures of the day: Clinton, Dole, probably Steve Forbes. Astonishingly, I received a reply in the mail some weeks later.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

“Thank you for sending along your cartoons,” the letter began. “Everyone here at George really enjoyed them and you are obviously very talented.” The next paragraph delivered the bad news in language that was then new to me—“Unfortunately, they are not right for us at this time ...”—but I remember my eyes reading past the rejection and instead focusing on the signature line below. The letter was signed by JFK Jr., who, at that point in his life, styled himself “John Kennedy” (foregoing his middle initial and the “Jr.”)

I had no expectation that the magazine would, as the letter’s writer promised, keep my cartoons “on file” in the event they might be used in the future. (George went kaput following Kennedy’s death in 1999.) It didn’t matter to me. After my parents had it framed, this rejection letter hung on my wall for years—officially a document of failure but, in my eyes, a reflection of a family occasionally capable of great accomplishment and grace. Simply put, Kennedy was under no obligation to reply to a wannabe cartoonist’s amateurish submission, but, to his credit, he treated me with appreciation and courtesy. Alas, he also gave me a preview of what became a lifetime of interacting with editors who judged my article ideas “not right for us at this time.”

Why do I place such confidence in the plans of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.? It is not merely that RFK Jr. has been right about so many issues—from the unconstitutional madness of the governmental response to the pandemic to the superiority of beef tallow for spud-frying—but also that his cousin, the president’s son, wrote an aspiring journalist such a polite and professional letter all those years ago.