Kevin McCarthy, Meet Frederick Gillett

The 118th Congress should take a page from the 68th.

The opening of the 118th Congress was marked by voting drama usually associated with the outcome of presidential primaries and elections. The election of House speakership is normally a quiet affair, but Republican Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy needed fifteen rounds to win the post.

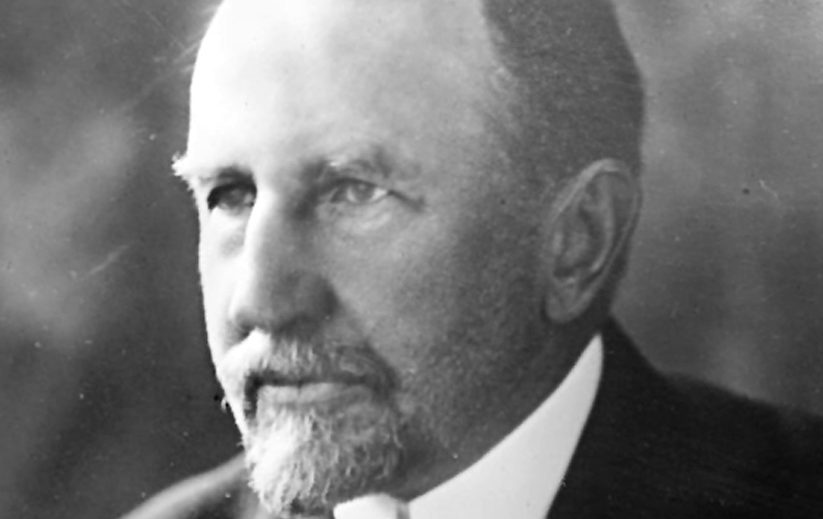

The unusual number of ballots introduced Americans to Frederick Gillett, who needed nine rounds over four days to secure the speakership in 1923. Gillett may not have been a prominent historical figure like Speaker Joe Cannon or so familiar as Nancy Pelosi, but his term was not insignificant.

The 118th Congress may have begun under less-than-auspicious circumstances, but America First conservatives would be fortunate if it equaled the legislative achievements of Gillett’s 68th Congress.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1924

Between 1860 and 1920, over 28 million immigrants entered America; midway through this period, the source of immigrants shifted from Northern and Western Europe to Southern and Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, these later arrivals endured more prejudice and discrimination than the former because of their unfamiliar languages, customs, and religious beliefs.

The matter reached a crossroads with America's entry into World War I. Amid President Woodrow Wilson's crackdown on dissent, business paranoia over growing socialist sentiment, and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Congress passed—over Wilson's veto—the Immigration Act of 1917, the first legislation to comprehensively restrict immigration.

After the war, Congress passed an emergency bill that introduced two new features: a numerical limit of 350,000 on the overall number of immigrations and a quota system to allocate spaces based on national origins. The quotas restricted annual immigration from a country to 3 percent of the existing foreign-born population as of the 1910 census. Wilson opposed this bill as well and used a pocket veto to prevent its passage.

In 1920, the American people repudiated Wilson and delivered a landslide to a decidedly conservative Republican presidential ticket of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge; voters similarly gave the Republicans massive majorities in both the House and Senate.

Having promised a return to "normalcy," President Harding promptly signed the Emergency Immigration Act into law.

A temporary measure set to expire in 1924, Rep. Albert Johnson of Illinois, the bill's sponsor, sought to make the provisions permanent in the 68th Congress.

Given the effectiveness of the Emergency Act in reducing immigration, Johnson's next bill simply tightened the restrictions. The law lowered the numerical limit to 165,000 and the quota to 2 percent as of the 1890 census. More pointedly, the original quota had been based on the number of people born outside of the United States. The new quota was based on the entire number of people born inside the country, which, in practice, dramatically restricted the entry of Southern and Eastern Europeans.

In the space of eight weeks, the 68th Congress passed the bill with overwhelming majorities in both houses. It was signed into law on May 26, 1924, by President Coolidge, who had ascended to the presidency after Harding's death in August 1923.

The Revenue Act of 1924

Established by constitutional amendment in 1913, the income tax was a foundational component of the progressive reform agenda. Conceived to mitigate rising income inequality, the original tax rates were modest, the highest being 7 percent.

Upon entry into World War I, the Wilson administration raised the required revenue by levying taxes at much higher rates—from a 15 percent top marginal rate in 1916 to 77 percent in 1918, before declining to 73 percent through 1921.

Such high rates during a national emergency were justified, but maintaining them three years after the war ended was simply confiscatory. When the economy fell into a sharp recession in 1920, Wilson's refusal to lower taxes was another factor in the Republicans' subsequent victory.

Harding’s plan to revive the economy entailed reducing government expenditures and lowering income tax rates.

Harding achieved an early success in the form of the Revenue Act of 1921, which lowered the top rate from 73 to 58 percent. Unemployment began to decline, and prices began to stabilize, albeit too late to prevent Republican losses in the 1922 midterm elections. The subsequently narrower majorities had the consequence of enhancing the leverage held by the party's remaining progressive insurgents, namely Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin.

In November 1923, the Coolidge administration transmitted a tax reduction proposal to the House. The draft legislation rapidly advanced in both chambers but this auspicious start was soon thwarted by an alliance of Republican progressives and Democrats that favored steeper progressive rates. Instead of the desired 25 percent, the bill only reduced the top rate from 58 to 46 percent. Coolidge reluctantly signed the bill on June 2, 1924.

The 68th Congress faced two principal challenges, one long-term and one immediate—establishing a durable regime for future immigration and right-sizing the government's relationship to the economy after World War I—and it succeeded.

In the space of ten days, Coolidge signed into law two bills passed by the 68th Congress to address these challenges.

In its day, the Immigration and Nationality Act was deemed a triumph; Johnson characterized it a "second Declaration of Independence."

While it is reviled today as the legal embodiment of American nativism, it is little appreciated how the act precluded the passage of legislation completely foreclosing immigration and preserved family reunification and unlimited immigration from the Western Hemisphere.

Unlike literacy tests and country-specific restrictions, the numeric restrictions were more transparent and inherently objective; their endurance through 1965 attested to their efficacy.

In contrast, the Revenue Act was considered a setback; Coolidge contended it did not “represent a sound permanent tax policy."

Rectifying the law's shortcomings became the centerpiece of the Republican Party's campaign in the upcoming 1924 presidential election. Coolidge easily defeated La Follette for the Republican nomination, and the party enthusiastically united behind him and a platform pledging to reduce taxes.

For its part, the Democratic Party had not yet fully reconciled itself to the conservative wave that had overwhelmed it in 1920. Only four years removed from the Wilson administration, Democrats still favored a more progressive tax structure and its platform denounced tax cuts as a giveaway to the wealthy.

Nevertheless, this opposition was a rare instance of agreement as the party convention was deadlocked between its two leading candidates; after 103 ballots, the party settled on a compromise candidate, John W. Davis, who had been Wilson's solicitor general but was now a prominent Wall Street lawyer.

After his defeat, La Follette abandoned the Republican Party; repelled by the relatively conservative Democratic platform, he entered the presidential race as the Progressive Party nominee. True to form, La Follette vowed to expand government intervention in the economy and institute a more progressive tax system.

Coolidge won the election in a historic landslide. Fortified by the mandate, the next Congress promptly passed a bill reducing the top rate from 46 to 25 percent, which Coolidge signed into law on February 26, 1926.

The economic benefits soon became manifest; between 1922 and 1929, the annual rate of growth averaged 4.7 percent while joblessness declined from 6.7 percent to 3.2 percent.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

The new Republican House faces comparable challenges. Amid the Second Great Inflation, America awaits a plan to right-size a bloated post-pandemic government. Imperiled by the catastrophe on the southern border, America needs a comprehensive new immigration regime.

The 118th Congress will be thwarted by the Democratic Senate and the Biden White House, but there is no reason it cannot similarly lay the foundation for a robust Republican platform in 2024.

Kevin McCarthy may not be Frederick Gillett, but conservatives would be lucky if the 118th Congress echoed the 68th.