Those “Vexed and Troubled” Puritans, the Poem Auden Hated, and Bulgarian Folk Music

There are those, Nicola Gardini writes, “who maintain that Latin does in fact have a purpose. Latin, according to this camp, teaches us how to reason and instills a certain discipline, which can then be applied to any other task. So Latin is just like math. I can’t tell you how many times I heard this growing up, and how often I hear it still! They defend Latin by granting it the merits of other branches of knowledge, while ignoring its own unique merits—without recognizing that Latin offers something that math can’t offer, just as math offers things that Latin can’t.” Latin is beautiful.

Anthony Daniels reviews What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading: “The title of this book is distinctly enigmatic. Who is the we to whom it refers? Certainly not to any group of people with whom I am acquainted, though I talk a lot about books with my friends. A better title might have been What Certain Literary Scholars in Search of New Secondary Fields of Study for Lack of Anything Else New to Do Talk About When They Go to Academic Conferences Whose Proceedings No One Will Read.”

Park MacDougald reviews Serotonin: “Serotonin is not a great novel. It is more melancholic and less bitter than some of Houellebecq’s other books, at the cost of being less entertaining. The plot drags in places, and it lacks the mordant humor that typically redeems the author’s pessimism. Yet the book ends on a curiously hopeful note, with a gesture toward the idea that love between men and women is an ‘illumination’ of God’s ‘instructions’ for our lives. This religious touch may represent a new direction for Houellebecq, a spark of light amid his relentless darkness. Or, given his generally cynical take on romantic love, it may turn out to be his blackest joke of all.”

Listen to a wonderful selection of little-heard Bulgarian folk music.

Terry Teachout on the Auden poem Auden hated: “Never did Auden employ his gift of accessibility more effectively than in ‘September 1, 1939,’ the poem he wrote immediately after Nazi Germany started World War II by invading Poland. Published in the New Republic that October, ‘September 1, 1939’ contains within its nine 11-line trimetric stanzas more widely quoted phrases than any of Auden’s other poems. It was there that he called the ’30s ‘a low dishonest decade,’ described the stunned members of his generation as ‘lost in a haunted wood, / Children afraid of the night / Who have never been happy or good,’ and—most memorably—warned his readers that they ‘must love one another or die’ . . . But Auden made no secret of disliking it, going so far as to call it ‘the most dishonest poem I have ever written’ in a 1967 letter and dismissing it as his ‘least favorite’ of his own poems in a later interview with the Paris Review. He cut the entire eighth stanza (in which the line about the necessity to ‘love one another’ appears) when he included ‘September 1, 1939’ in his 1945 Collected Poems, and then said that it was ‘a damned lie’ to say that ‘we must love one another or die’ and changed ‘or’ to ‘and.’”

The itinerant revolutionary: “Victor Serge was born into exile in 1890 and died in exile 57 years later. The child of Russian radicals who fled to Belgium in the wake of the plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander II, Serge (né Victor Lvovich Kibalchich) embraced anarchism and was jailed for writing in support of a band of notorious, quasi-anarchist French bank-robbers known as the Bonnot Gang. He subsequently participated in the abortive anarcho-syndicalist Catalan uprising of 1917, was again imprisoned and then made his way across Europe to his parents’ now revolutionary homeland, where he made common cause with the Bolsheviks. Dispatched in the mid-1920s to Germany and Vienna as a Comintern agent, Serge came to know many of the world’s leading revolutionaries. He returned to the Soviet Union to join the anti-Stalin opposition, led by Leon Trotsky. With the opposition’s defeat and his resulting expulsion from the Communist Party, he became a full-time writer; his work was mailed out of Russia for publication in France. Arrested once more and exiled to Central Asia, he managed to avoid liquidation thanks in part to a series of organized protests by left-wing French intellectuals, including André Gide . . . When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he backed the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, the same independent Marxist faction for whom George Orwell fought; published his novel of the Gulag, Midnight in the Century; and worked on what would be his best-known book, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, a fictionalized account of the purge trials less monolithic in its analysis of Bolshevik psychology than Arthur Koestler’s contemporaneous Darkness at Noon.”

Essay of the Day:

Students are sometimes taught that John Winthrop was comparing America to ancient Israel in “A Model of Christian Charity” when he told his fellow Puritans as they headed towards the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “we shall be as a city upon a hill; the eyes of all people are upon us.” A new book disputes the claim and performs a “rescue operation of Puritanism itself,” Andrew Delbanco writes in The Nation:

“Rather than instigating the pernicious idea of the United States as God’s most favored nation, the Puritans, he argues, were unsure of their worthiness and subjected themselves to ‘the moral scrutiny of the world.’

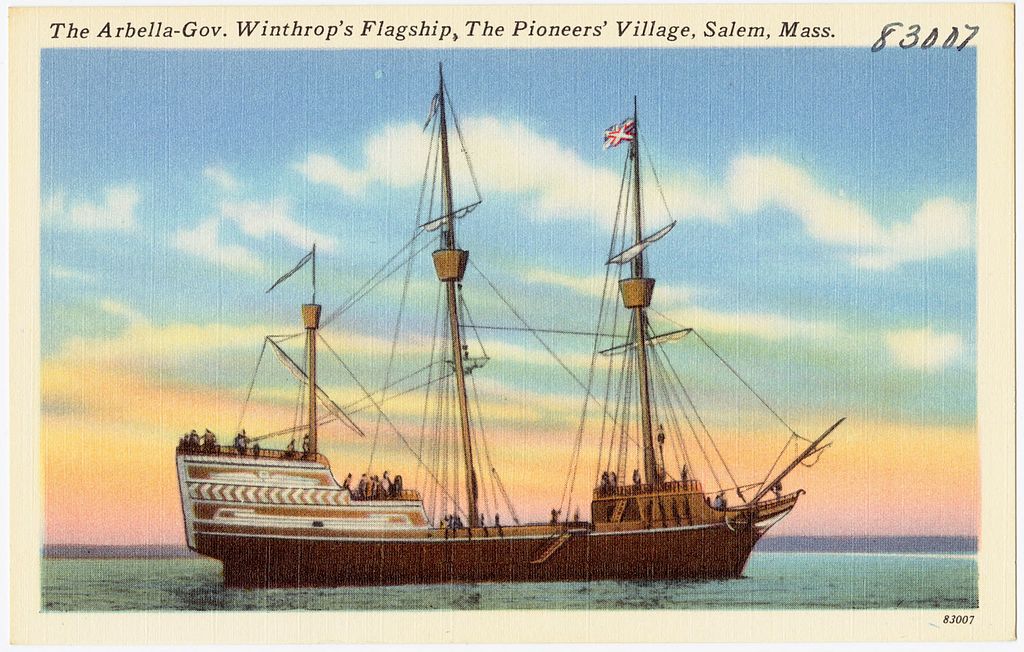

“To begin with, Rodgers shows that almost everything we thought we knew about Winthrop’s speech is wrong. Ever since a copyist (it’s unclear when) scrawled ‘Written on board the Arrabella on the Atlantick Ocean’ on a cover sheet attached to the surviving manuscript, Winthrop has been imagined as raising his voice into the roaring wind on the roiling sea. But in fact, he was more likely to have delivered the speech—often called a lay sermon because he was not an ordained minister—in Southampton before embarking. Or he may never have delivered it at all.

For more than 200 years the work lay in manuscript, until the Massachusetts Historical Society published it in 1838, in a collection of documents in which it was preceded by a few poems just a cut above doggerel and followed by a short history of the US Postal Service. Throughout the 19th century, the speech remained little more than an antiquarian curiosity. Even in the early 20th century, when scholars began to take note of it, no one attributed to it any claim of divine special favor. Writing in 1916, the Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison, who traced his New England ancestry to the 1660s, heard in it an ‘emphasis on collectivism rather than individualism’—as if Winthrop had been a secret socialist.

“The modern career of Winthrop’s speech got underway in the 1930s, when a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Perry Miller, went east to Harvard, in part to study with Morison. Miller, who also had New England roots (he was related to Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy) but cultivated the personal style of a Midwestern tough guy in the Dreiser-Hemingway mode, had dropped out of college for a while and joined the merchant marine, which took him, among other places, to the west coast of Africa. It was there, he later recalled in brash emulation of Edward Gibbon—who had been seized by the ambition to write The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire while contemplating the ruins of the Forum—that Miller discovered his destiny while unloading drums of American oil. Suddenly, he grasped his life’s mission: to expound to the world ‘what I took to be the innermost propulsion of the United States.’ This propulsion, Miller insisted, had been ignited in colonial New England.”

* * *

“Rodgers insists that neither Miller’s version of the Puritans attempting to save the Old World by example nor Bercovitch’s version as the self-appointed vanguard in the cosmic drama of salvation gets Winthrop and his contemporaries right. In this judgment, Rodgers is not alone. In a sweeping new history of what he calls ‘the city-state of Boston,’ Yale historian Mark Peterson laments that ‘these interpretations badly distort the meaning and influence of the governor’s words,’ and Michael P. Winship, in a valuable new history of Puritanism, Hot Protestants, observes that the idea that the ‘puritans envisioned New England as the site of the millennium’s New Jerusalem’ has ‘been thoroughly discredited.’ And so the pendulum swings. The Puritans seem to be coming back into view not as progenitors of some future America but as they appeared to themselves in their own time, what the mid-20th-century historian Carl Bridenbaugh called ‘vexed and troubled Englishmen.’”

“In taking the turn to a more historicist approach, it makes sense, as Rodgers does, to stick with Winthrop as the Puritans’ representative man. Before emigrating to America, Winthrop struggled to negotiate the accelerating transformation of England from a relatively static feudal order to a dynamic and disruptive—morally as well as socially—market economy. A member of the landed gentry, he feared that England was becoming a place where ‘no man’s estate almost will suffice to keep sail with his equals, and he who fails herein must live in scorn and contempt; hence it comes that all arts and trades are carried in that deceitful and unrighteous course, as it is almost impossible for a good and upright man to maintain his charge and live comfortably in any of them.’ In short, it was becoming harder for men of Winthrop’s rank to be both virtuous and prosperous.”

Photo: The Sun and Mercury

Poem: Daniel Brown, “First Job”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments