Israel’s Iran Agenda

When is pointing out an opponent’s motivation an effective tactic in foreign-policy debate? During the Cold War, I published my first large article documenting that E.P. Thompson (a leading proponent of the “nuclear freeze”) was not merely (as he was customarily presented) a pleasantly “utopian” socialist with a charming shock of white hair, but a figure with a somewhat hardline Marxist history and a long record as an opponent of NATO and advocate of accommodating the Soviet Union. Thirty years later I have white hair myself, E.P. Thompson has passed on, and all are grateful that the Cold War concluded without nuclear bombs going off. As to whether or not my type of argument—made in countless variations by hundreds of writers during the rhetorical Cold War—was effective, many thought it was. The piece was quoted, circulated, and advanced the professional aspirations of its author. And in fact it was an easier argument to make than to wade into the impossible-to-calculate unknowables about how a strategy of non-belligerence might save Europe from both the threat of war and Soviet dominance.

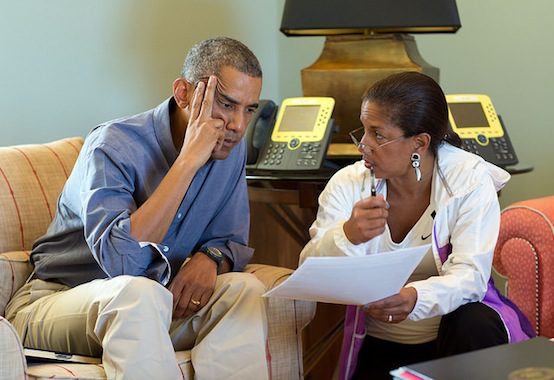

This issue of motivation arises because of the House’s vote on Wednesday to ramp up sanctions on Iran. The vote was rushed to floor before recess not so that sanctions can be escalated anytime soon (the Senate won’t take up the bill till the fall, if ever) but because AIPAC—representing in Washington the perspectives of Israel’s current government—wants to short circuit any chance of meaningful negotiation between the Obama administration and Iran’s newly elected president. One goal of the bill is to demonstrate to Iran’s leaders, through a landslide House vote, that America is deeply, almost inherently, hostile and to undercut whatever small gestures of peaceful diplomacy that Obama and the new Rouhani team have each been making since the latter’s election last June.

Like Paul Pillar in his excellent analysis of the consequences of the passage of the sanctions bill, I believe that most of those who voted for it don’t think it will necessarily damage the prospect of negotiations, or at least not enough to make a difference. Most congressmen believe passionately in their own re-election above anything else, and few want to face a really well-funded AIPAC-backed candidate during their next four election cycles. And so it’s an easy go-along with the majority vote, not a vote actually for war or even for non-negotiation. Several days earlier, 130 congressmen had signed (against AIPAC’s subdued opposition) a pro-diplomacy letter, meaning that many congressmen signed both.

One thing at stake is the the power of foreign state to influence America’s choices about war and peace. Someone said to me recently that AIPAC really is like the NRA. Actually no. The NRA represents the views of a significant slice of Americans, effectively amplifying currents deeply rooted in American history. Its actual real-world impact is at the margins. The NRA could vanish tomorrow and there would still be 200 million guns, mostly legal, inside the country’s borders in ten years’ time.

War with Iran is different. There is no way the United States would be so near to war, no way even the United States would seem irrevocably hostile to Iran, so lacking real diplomatic contact with the country, without the machinations of the Israel lobby. The Iranian revolution and the hostage crisis were long ago, and there are powerful human and economic incentives, on both sides, to work our way towards some sort of detente.

But an Iran at peace with the U.S. would still be a rival to Israel for influence in the Mideast. Unlike the countries in the Arab world, Iran is a cohesive, fairly effective and fairly modern state, with considerable technical and scientific infrastructure. It considers itself worthy of being treated as a regional power. And Israel doesn’t want that. Period. It prefers, understandably, weak rivals. So Israel works overtime to scare Americans to death about Iran. Credit AIPAC for effectiveness—it has Congress eating out of its hand.

A final word. Here is Ali Gharib’s fine piece on the congressional vote. It is strong both because of its analysis of the impact of the stupid vote—which doesn’t do the slightest thing to lessen the chances of Iran’s procurement of a nuclear weapon—and because he says quite clearly and emphatically that it was AIPAC’s vote. That’s something which needs to be said openly.

When TAC started, we ran a wonderful long essay by diplomatic historian Paul Schroeder pointing out the stake the U.S. had in international law and the state system and the folly of Washington upending that order by invading Iraq. At the end, Schroeder included four footnotes, one of which said:

It is common for great powers to try to fight wars by proxy, getting smaller powers to fight for their interests. This would be the first instance I know where a great power (in fact, a superpower) would do the fighting as the proxy of a small client state.

Schroeder’s footnote number 4 was widely quoted, more than any other passage in a complex and nuanced essay. I think this is because it got at a truth which many Americans are extremely reluctant to face but whose grave importance they nonetheless sense. Given the enormity of the human, financial, and political cost of the Iraq War, one might wish that our elected representatives would be more careful about being sent down down a very similar path a mere decade later.